The Finale

August 20, 2015It’s fair to assume that I have now had sufficient time to reflect on the goings-on of the past three weeks. But although time has passed since the inaugural SPP conclusion, I have not freed my mind of its contents.

Many have asked me what I thought of the program; they knew of our trips to the prisons and talks with MIIS faculty, and of course almost everyone knew of the presence of Dr. Christopher M itchell, but I think my answer to the question, “How was it?” still surprised them. If I were told to pin point three of the most academically informative and thought-provoking weeks of my life, it may have been those.

itchell, but I think my answer to the question, “How was it?” still surprised them. If I were told to pin point three of the most academically informative and thought-provoking weeks of my life, it may have been those.

There were many dynamics at work that contributed to this overall feeling I am still having; the lecturing staff was phenomenal. Each one had a different opinion or way of talking about sometimes-similar themes, and if we were lucky, we would start to see the personality of the lecturers shine through their presentations. The Mt. Madonna Center was a place dreams are made of! For me, it was the perfect combination of healthy, isolated, peaceful landscaping that provided an amazing environment for learning about conflict resolution (although we disrupted that peace on more than one occasion in the “classroom”).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the group of students that participated made this program (credit to Dr. Iyer, who’s work is never a coinsidence) . This is not to take away from those other aspects I mentioned though, as those parts were always going to be great. But the experiences of each individual came out in every single session, and that enabled me to enter into this duality of learning: peace building and historical/cultural/social contexts of the countries represented. The atrocities that took place in the Balkans are now ingrained in my memory forever. What it is like to be a “do-er” on the ground in Nepal couldn’t escape my mind if I wanted it to. There are 14 other stories that I will forever be able to pull from and talk about to other people with such robust credibility, and for that “Cosmopolitan Street Cred” (thank you Peter Shaw), I am eternally thankful.

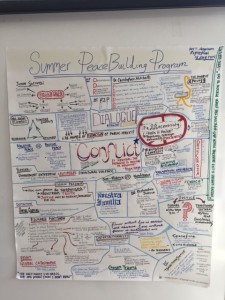

To round this up, I don’t foresee myself forgetting much of what was covered in the past three weeks. HOWEVER, I don’t trust myself. So, I have spent some time combining what I perceive to be the most important things from these weeks, in an effort not to forget, but also to relive those moments that I loved. Thank you all for changing the way I see the world.

Posted by Daniel Pavitt

Posted by Daniel Pavitt