Class Assignments

Assignment #3: Diversity and Access to Education

Finnish Equality in Society and Education

Introduction

A large aspect of Finnish culture has always been a dedication to equality and much of this can be seen in the country’s educational policies. And with PISA scores like these, it’s clear that these policies have had a positive effect. In Finland, “every child should have exactly the same opportunity to learn, regardless of family background, income, or geographic location. Education has been seen first and foremost not as a way to produce star performers, but as an instrument to even out social inequality” (Partanen, 2011). The Finnish education system has promoted equality over high-achievement by putting a large amount of resources into special education, publicly funded school equality, gender equality in public policy, and immigrant integration. And few other countries can boast of the same success as Finland.

PISA Results and Equality

When it comes to equity in education, Finland has demonstrated that it is up to the task. Although Finland does not support standardized testing, the one standardized test it does take, PISA, has revealed that there is a great amount of equality in student performance. Results from the PISA test show that, not only do Finnish pupils score very high, but also that the number of weak performers is very low (Kivirauma and Ruoho, 2007). The standard deviation of test results, which shows variation in student performance, is among the lowest in all OECD countries (Valijarvi et al., 2002). Within Finland, PISA results have shown that a pupil’s demographic, economic, social and cultural status has below average impact on that student’s performance (OECD, 2004) or, in other words, the country is in a “situation in which students’ performance is nearly independent of their sex, domicile, school or socio-economic background” (Kivirauma and Ruoho, 2007).

Special Education

There are many reasons for this equality, one of which is Finland’s emphasis on part-time special education. This strategy, which has its roots in the Comprehensive School Act of 1968, aims at addressing issues problematic to a pupil’s learning and progress as early as possible while still including him or her in regular classes. During the 1960’s, elementary and middle schools were unified and there was a concern that this unification would lead to problems of mixed abilities due to heterogeneity in the classroom. To avoid this, a countrywide system of part-time special education was introduced (Kivirauma and Ruoho, 2007).

One aspect of this strategy entails creating teachers with a high amount of training in special education and creating many of them. Reforms of the 1960’s saw the establishment of a new, high-quality and uniform system of teacher training, which included part-time special education. As part of the master’s degree that all teachers must obtain, special education is a large part of the curriculum. The number of part-time special education teachers hired in basic education in Finland increased 20-fold between 1967 and 1977. This has continued and, in 2002, every tenth teacher was a special education teacher and 30% of teachers were part-time special education teachers (Kivirauma and Ruoho, 2007). This vast resource of part-time special education teachers is “one of the key factors explaining the equality of Finnish outcomes in the PISA study” (Kivirauma and Ruoho, 2007). With this quality and quantity of special education teachers, it is simply much harder for students to fall behind.

This high number of special-education teachers also reflects the high quantity of Finnish pupils involved in special education. In 2003, 18% of all Finnish children were classified as special educational needs students. This is significantly higher than in other countries. For example, in Germany, only 5.3% of students are classified as special educational needs students. (Kivirauma and Ruoho, 2007). “It can be concluded that Finland has the world record in terms of the quantity of special education given to basic education students (Kivirauma and Ruoho, 2007). However, the definition of special needs in Finland is much broader.

Special education often has connotations of students with a major physical or mental disability but, in Finland, the term is used quite flexibly and is primarily aimed at students in need of minor assistance outside of regular class time. Finland’s policy towards special education is also highly focused on early intervention in a pupil’s education, often in the first three years of schooling, and it puts particular stress on the treatment of language-related problems. In fact, support for spoken and written mother tongue language skills accounts for more than two-thirds of all part-time special education (Kivirauma and Ruoho, 293). This high number of special needs teachers and the high number of children that receive special needs assistance contributes greatly to the equality seen in the Finnish education system.

School Equality, Choice and Competition

Another ingredient in Finland’s success at achieving educational equity is the lack of competition and difference amongst schools. First, there are no private schools or universities and the small number of independent schools in Finland are publicly financed. Schools are not allowed to charge tuition fees. This means that practically everyone in Finland attends public school, from pre-Kindergarten to the Ph.D. level (Partanen, 2011). This prevents privately- and well-funded schools from getting an edge on public schools. In addition, there is much less competition in Finland as this is not part of Finnish culture as it is part of American culture. “There are no lists of best schools or teachers in Finland. The main driver of education policy is not competition between teachers and between schools, but cooperation” (Partanen, 2011). This means that schools generally provide the same quality level to all students in all parts of the country. In the U.S., much attention and money is given to choosing the right school but, in Finland, there is no choosing or benefit to doing so. From the rural Lapland of northern Finland to the suburbs of Helsinki, schools are relatively equal.

Immigrants

Finland has also achieved success in providing educational equality towards its immigrants. Since the 1980s, there has been a rapid growth in the country’s foreign-born population but, even with this influx of immigrants, the education system still achieves a high level of equality (Kilpi-Jakonen, 2012). Finland’s immigrant education policy is to “provide people moving to Finland with opportunities to function as equal members of Finnish society and guarantee immigrants the same educational opportunities as other citizens” (Finnish National Board of Education, 2013). One way it does so is through the part-time special education mentioned previously. As immigrants have special needs, in terms of language and culture, they can also be classified as special needs students and receive additional assistance during their schooling.

Besides equality, Finnish policy towards immigrant education also focuses on integration, functional bilingualism and multiculturalism. Finland aims to integrate immigrants into the Finnish education system and society as well as support their cultural and linguistic identity. For example, one goal of Finnish immigrant education is to foster “well-functioning bilingualism as possible so that, in addition to Finnish (or Swedish), [immigrants] will also have a command of their own native language” (Finnish National Board of Education, 2013). While immigrants maintain their own language and culture, instruction in Finnish or Swedish, which are the two official languages of Finland, is organized for immigrants of all ages (Finnish National Board of Education, 2013).

The Gender Effect

Another aspect of Finnish equality, and perhaps an interesting cause of equity in the Finnish education system, is the country’s policies towards gender. Finland has gone far in achieving gender equality and, at the moment, 43% of members of Parliament and 47% of government ministers are female (Strauss, 2012). In 2000, the first female president was elected and, in 2003, the first female prime minister came into office. Gender quotas were also established in local public boards, committees and councils as well so that at least 40% of each gender was represented. Not only does this show wider equality in society, it is also argued that this is one reason for Finland’s success in education. “Given the intimate understanding most women have of children’s needs, it stands to reason that women legislators probably make better policy for children” (Strauss, 2012). Having women in power has led to numerous policies directed at the development of healthy children, from a substantial maternity leave to an emphasis on exercise and a 75-minute school recess.

Welfare State

Another factor in Finland’s educational equality, and in society in general, is the country’s strong welfare system. Besides supporting a general economic equality, Finland’s welfare system means that Finnish students can travel to and attend school free of charge, have access to free school lunches, healthcare, psychological counseling, and individualized student guidance (Partanen, 2011). This means that a student will never be unable to attend school because of health problems, family troubles, excessive mobility, or financial concerns. “The involvement of the strong Finnish welfare state is crucial to the success of education” (OECD, 2005).

Homogeneity and Size

It is often argued that Finland’s educational success and equality is a result of the country’s perceived homogeneity and small size, however this is not the case. Although Finland is a relatively homogenous country, the number of foreign-born residents in Finland doubled during the last decade and the country did not lose is edge in education (Partanen, 2011). Norway, which is also relatively homogenous and small, approaches education in the same manner as the U.S., with standardized testing, lesser educated teachers, etc., but the country only gets mediocre performance results in PISA tests (Abrams, 2011). One could even compare Finland’s homogeneity to that of American states. In 2010, there were 18 states in the U.S. that had identical or significantly smaller percentages of foreign-born residents than Finland (Partanen, 2011). Educational policy, according to Abrams, is more important to the success of a country’s school system than the nation’s size and ethnic makeup (Abrams, 2011).

Conclusion

Finland has achieved a remarkable amount of equality in its education system. This equality is visible in its PISA results and cannot be accounted for by the country’s relative homogeneity and small size. Rather, it is due to the country’s welfare system, its dedication to gender equality and immigrant integration, public funding of equal schools, and its successful system of special needs education as well as the resources put into that system and its teachers. As equality is a part of Finnish culture, it is a major goal and result of its educational policy.

Sources

Abrams, Samuel E. (2011). The Children Must Play. New Republic. Jan. 28, 2011. Website: http://www.newrepublic.com/article/politics/82329/education-reform-Finland-US#

Finnish National Board of Education. 2013. Website: http://www.oph.fi/english/education/language_and_cultural_minorities

Kilpi- Jakonen, Elina. 2012. Does Finnish Educational Equality Extend to Children of Immigrants? Nordic Journal of Migration Research. June 2012, 2(2): 167-181. Website: https://ktl.jyu.fi/img/portal/8317/PISA_2003_screen.pdf

Kivirauma, Joel and Kari Ruoho. (2007). Excellence Through Special Education: Lessons From Finnish School Reform. Review of Education, 2007, 53: 283-302.

OECD. (2005). Finland Country Note. Equity in Education: Thematic Review. April 2005. http://www.oecd.org/education/country-studies/36376641.pdf

Partanen, Anu. (2011). What Americans Keep Ignoring About Finland’s School Success. The Atlantic. Dec. 29, 2011. Website: http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/12/what-americans-keep-ignoring-about-finlands-school-success/250564/

Strauss, Valerie. (2012). A new Finnish lesson: Why gender equality matters in school reform. The Washington Post. Sept. 6, 2012. Website: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/post/a-new-finnish-lesson-why-gender-equality-matters-in-school-reform/2012/09/05/3703ad4c-f778-11e1-8253-3f495ae70650_blog.html

Valijarvi, J. and P. Linnakyla. (2002). Competence for the futre. PISA 2000 in Finland. University of Jyvaskyla: Institute for Educational Research.

Assignment #2: Contemporary Education Systems

Finland’s Teachers: A Virtuous Cycle

As mentioned previously, Finland’s education system is known throughout the world for its quality, equality and inclusiveness. There are a number of factors contributing to its success, many of which stem from the nation’s culture, philosophy and history, but one factor clearly sets the country apart: its teachers. “Without excellent teachers Finland’s current international success would have been impossible” (Sahlberg 2010). The force behind Finland’s success with teaching takes the form of a virtuous cycle that involves high demand for teaching careers, high competition and selectivity, high quality and free training, and a large amount of trust, prestige and respect placed on teachers. I’ve outlined this cycle below.

High Demand for Education and Careers in Teaching

The path to becoming a Finnish teacher begins upon being accepted into a higher education institution’s teacher education program, and this is no easy task. There are eleven universities that have teacher education programs in Finland and they are very selective. The demand for an education in teaching is so high in the country that the amount of applications for enrollment far exceeds the amount of spaces in these programs. “Among all categories of teacher education, about 5,000 teachers are selected from about 20,000 applicants” (Sahlberg 2010). In the case of primary school teachers, the situation is even more competitive as, annually, only about 1 in every 10 applicants are accepted to become teachers in primary schools (Sahlberg 2010).

Competition and Selectivity

With this kind of demand for teacher education and this high number of applicants, teacher-training programs have the ability to take only the best and the brightest. In doing so, applicants have to pass through a number of steps. For primary school teachers, there are two phases to the selection process. First, an initial group of candidates is selected based on the results of a matriculation exam, the candidates’ high school diploma and grades, and relevant records of extracurricular accomplishments. Second, this group of candidates must complete a written examination on assigned books on pedagogy, complete an observed activity replicating a school situation in which social interaction and communication skills are tested, and complete an interview in which they are asked to explain why they have decided to become teachers.

Free and High-Quality Teacher Education

Once accepted into a teacher education program, a Finn still has a long way to go, as education requirements for teaching positions are high. While preschool and kindergarten teaching positions require a bachelor’s degree, teaching positions in primary and secondary schools require a bachelor’s and master’s degree. As Finland is part of the European Higher Education Area framework of the Bologna Process, a bachelor’s degree program generally last three years of full-time study and a master’s degree program last two years. On this schedule, full-time students acquire 60 ECTS credits per year with each credit requiring about 25 to 30 hours of work. As this represents full-time study, it can take between five and seven and a half years to complete a teacher’s education (Ministry of Education, 2007). Fortunately for future teachers in Finland, these advanced degrees are completely paid for by the Finnish government.

During their studies, a teacher’s education consists of a balanced development of personal and professional competencies. Future primary school teachers major in education in general and upper-grade teachers concentrate in the subject area in which they intend to teach, which also includes didactics and pedagogical content knowledge specific to that subject. In this second case, teachers are not only experts in teaching but also experts in the knowledge area in which they teach. As there are only eleven universities with teacher education programs in Finland, quality control and consistent standards are easy to control (NCEE 2013).

The curriculum is also very broad-based and balances both theory and practice as teacher-training programs include pedagogical theories and research methodologies as well as practical experience, in which students observe lessons and deliver lessons under observation. “The intention is to link theory and practice in a sufficiently close relationship that a teacher may be able to resolve everyday teaching problems on the basis of his or her theoretical knowledge” (Kansanen 2003). This means that “prospective teachers possess deep professional insight into education from several perspectives, including educational psychology and sociology, curriculum theories, assessment, special-needs education, and pedagogical content knowledge in selected subject areas” (Sahlberg 2010). Each student also completes a master’s thesis in either the general field of education or within their selected subject of teaching.

Prestige, Respect and Autonomy

Another part of Finland’s successful cycle of quality teachers is the prestige and importance that society places on teachers. Education is highly valued in Finnish society. Part of this may result from the fact that there is a large number of female policymakers in Finland (Strauss 2012) and this will be discussed in the next assignment of this blog. But, in general, “education has always been an integral part of Finnish culture and society, and teachers currently enjoy great respect and trust in Finland. Finns regard teaching as a noble, prestigious profession—akin to medicine, law, or economics—and one driven by moral purpose rather than material interests” (Sahlberg 2007).

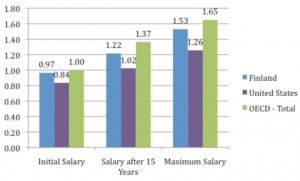

And it is clear that Finns do not become teachers for the salaries. Finnish teachers earn very close to the national average salary, which is about equal to what a mid-career middle-school teacher earns annually in an OECD nation, about $38,500 (OECD, 2008). Salaries range from about $34,000 to $51,000 and they are somewhat lower than other professional salaries in Finland (NCEE 2013).

Ratio of Lower Secondary Education Teachers’ Salary to GDP per Capita (NCEE 2008):

But despite the insignificant salary, high school graduates still line up at universities, wanting to become teachers because they respect the profession. “Among young Finns, teaching is consistently the most admired profession in regular opinion polls of high school graduates” (Helsingin Sanomat, 2004).

There are a number of reasons why teachers garner such respect in Finland. One reason, as mentioned before, is the amount of education they receive and the fact that it is completely paid for by the government. Any position that receives such government support is bound to be respected and desired by those considering future occupations. Another reason for the admiration of teachers is that, to get this publicly funded and high quality education, future teachers must pass through the highly selective process mentioned earlier. “Because Finland has very high standards that must be met to enter teacher preparation programs, getting in confers prestige on the successful applicant” (NCEE 2013).

Teachers are also given a great amount of trust and autonomy in their work. There is a well thought-out national curriculum in Finland but it serves mainly as a guide and teachers are encouraged to use their own creativity and innovation in using that curriculum in the classroom. Teachers “have both a curriculum worth teaching to and the kind of autonomy in how they approach it that is characteristic only of the high status professions” (NCEE 2013). Principals exert minimal control or authority over the teachers within the school. Finnish teachers are also amongst the most trusted in the world and it shows in the fact that there are no standardized tests that measure the comparative worth of different teachers or schools. Instead of test-based accountability, the Finnish system relies on the quality and accountability of its expert and committed teachers.

“This high level of trust, the intellectual challenges of a curriculum that aims high and involves a regimen of constant invention, the satisfaction of knowing that you have been admitted to a profession that is very hard to get into, the knowledge that you will be working with others who have the same attainments and the professional autonomy usually associated only with the highest status professions — all this makes for a very attractive job.” (NCEE 2013)

“More important than salaries are such factors as high social prestige, professional autonomy in schools, and the ethos of teaching as a service to society and the public good. Thus, young Finns see teaching as a career on a par with other professions where people work independently and rely on scientific knowledge and skills that they gained through university studies.” (Sahlberg 2010)

The attractiveness of the teaching profession explains the high volume of applications for university teacher education programs. It also explains the high retention rate of teachers. About 90% of teachers remain in the profession for their entire careers (NCEE 2013.

Another interesting facet of Finnish teaching is that they spend far less time doing formal teaching but do more work outside of class time. In the U.S., a teacher teaches about 1,080 hours annually but a Finnish teacher only teaches 600 hours (OECD 2008). This adds up to four 45-minute lessons per day. But many of a teacher’s duties are outside of class, including designing innovative ways to teach the curriculum, preparing for class, doing assessments, improving the school as a whole, and working within the community (Sahlberg 2010). The only area found lacking is support for professional development. Finnish teachers spend about seven working days per year on professional development. This is considered to be too little and the Finnish Ministry of Education, along with municipalities, plans to double public funding for teacher professional development by 2016 (Finnish Ministry of Education 2009).

Conclusion

A major contributor to the success of the Finnish education system is the success of its teachers. They are made up of the best and brightest, are highly trained, and are given a great amount of autonomy and trust because they are highly valued and respected. In return, they are highly valued and respected because they are made up of the best and the brightest, are highly trained and are given a great amount of autonomy and trust. This cycle of believing in the importance of teachers and acting upon that belief is what makes education strong in Finnish culture and society. Observers often claim that the Finnish case cannot be replicated because the status of teachers is a cultural characteristic and this cannot be created in other countries. Although Finnish culture does value teachers, this characteristic was founded and is supported by policies that elevate the role of teachers. “The status of teachers on closer examination appears to be in large measure the result of the implementation of specific policies and practices…that are quite replicable” (NCEE 2013). These same policies and practices could be utilized in the U.S. and other countries, raising the bar on teachers and education in general.

Bibliography:

Kansanen, Pertii. (2003). Teacher Education in Finland: Current Models and New Developments. In B. Moon, L Vlasceanu, & C. Barrows (Eds.), Institutional approaches to teacher education within higher education in Europe: Current models and new developments (pp. 85-108) Bucharest: UNESCO – Cepes.

Ministry of Education (2007). Opettajankoulutus 2020 [Teacher education 2020]. Committee Report 2007: 44. Helsinki: Ministry of Education.

NCEE. 2013. Center on International Education Benchmarking: Finland. http://www.ncee.org/programs-affiliates/center-on-international-education-benchmarking/top-performing-countries/finland-overview/finland-teacher-and-principal-quality/

OECD (2008). Education at a glance. Education indicators. Paris: OECD.

Sahlberg, Pasi. 2010. The Secret to Finland’s Success: Educating Teachers. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education – Research Brief. September 2010. http://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/secret-finland’s-success-educating-teachers.pdf

Strauss, Valerie. (2012). A New Finnish Lesson: Why Gender Equality Matters in School Reform. Washington Post. 9/6/12. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/post/a-new-finnish-lesson-why-gender-equality-matters-in-school-reform/2012/09/05/3703ad4c-f778-11e1-8253-3f495ae70650_blog.html

Westbury, I., Hansen, S-E., Kansanen, P. & Bjorkvist, O. (2005) Teacher education for research-based practice in expanded roles: Finland’s experience. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 49(5), 475-485.

Assignment #1:

Education in Finland: Cultural, Philosophical and Historical Influences

When policymakers and academics look for examples of successful education, they often look to Finland. This northern, Nordic nation boasts one of the best education systems in the world and is often used as an example of best practices. Although Finland has the advantages of a homogenous and socioeconomically equal population with a high standard of living, the policies and culture surrounding education offer unique insights into what works and what does not. And according to various statistics, Finland’s system is working. Finland has ranked at or near the top in PISA scores (OECD 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009). Ninety-three percent of Finnish students graduate from high school, which is 17.5% higher than in the U.S., and 66 percent go on to higher education, the highest rate in the European Union. And through all this, Finland spends about 30% less per student than in the U.S. (Hancock 2011).

Finland has had a long history of education but most of its success came late in the 20th century with a massive education reformation. The nation’s history, culture and philosophy are evident in its new system, particularly in its treatment of teachers, inclusiveness and accessibility, egalitarianism, avoidance of testing, nurturing of children outside the classroom, and localization along national curriculum guidelines.

Historical Foundations

As it is in many Western countries, Finnish education has its beginnings in the Church. Beginning in the 12th century, Finland was part of the Kingdom of Sweden for 600 years and, in the 16th century, Swedish King Gustav Vasa established the Lutheran Church as the national church of Finland (FNBE 2010). Schooling began in the Church because Lutheran teachings included the idea that people should be able to read the bible and so the church began to teach Finns how to read. In fact, literacy even became a prerequisite to marriage. During this time, the social and religious influences of Sweden and the Lutheran church pulled Finland towards Western culture, which has affected its education system to this day. Although Finland was also part of Czarist Russia for 100 years, beginning in 1809, the legislation and social system that emerged during its time under the Kingdom of Sweden did not change. Finland ended up on the Western side of the European and Slavic divide.

While under the Kingdom of Sweden, Swedish was the official language of Finland even though Finnish was the native language of most of the population. However, as nationalism grew throughout the 19th century, also grew a demand for the Finnish language to be used in schools. In 1858, the first secondary school began teaching lessons in Finnish and, from then on, the number of schools grew drastically. Although both Finnish and Swedish are official languages in Finland now, all schools teach in Finnish.

The growth of industry and construction during the 19th century led to higher demand for vocational schooling and, in 1869, the Church lost its control over education when Finland established its own Board of Education to govern its new, growing system of schools. In 1898, Finland made its first step towards providing education to all with a decree obligating local authorities to provide all school-aged children with an opportunity to attend school (FNBE 2010). The value of providing equal education to all would grow to be one of the Finnish education system’s greatest achievements.

Once Finland gained its independence in 1917, its high value in providing quality education to all was immediately evident. The Constitution of Finland, enacted in 1919, specified the government’s obligation to “provide for general compulsory education and for basic education free of charge” (FNBE 2010). In 1921, general compulsory education was made law. But Finland also suffered greatly during this time due to a civil war and conflicts with both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Until the 1960s, Finland faced economic hardships and a stifling Soviet influence. During this time, the country’s “education system looked far different than it does today” (Porter-Magee 2012).

In the 1960s, things started to change and education was the key. At this time, “Lawmakers landed on a deceptively simple plan that formed the foundation for everything to come” when Finland “choose public education as its best shot at economic recovery” (Hancock 2011). The country enacted a nationwide focus on preparing students for a knowledge economy and a new basic education system was developed. Finland organized its public schools into one system of comprehensive schools, called peruskoulu, for students aged 7 to 16, and made a number of other reforms. These reforms reflect and contribute to modern Finnish culture and society and they are important aspects of the country’s education system.

Highly Qualified and Respected Teachers

One of the most important philosophies of Finnish education is the importance of the teacher. “Policymakers understood the importance of teacher quality in driving student achievement, and they invested heavily in it” (Porter-Magee 2012). In 1979, education reformers made teachers a respected and valued profession. They made it a requirement that every teacher, all the way down to primary school, earn a fifth-year master’s degree in theory and practice and determined that the state would pay for it. “From then on, teachers were effectively granted equal status with doctors and lawyers” (Hancock 2011). Every teacher, from cities to rural villages, had the same high level of education and training. Since then, there have been a great deal more applicants for teaching programs than positions because of the attractiveness of the profession. “Teaching has become the most highly esteemed profession. Not the highest paid, but the most highly esteemed” (Sirota 2011). Only 1 out of every 10 people who apply to become teachers makes it to the classroom (Sirota 2011). For example, in 2010, there were about 6,600 applicants for 660 primary school training slots (Sahlberg 2012). This is particularly interesting because the average salary for a teacher is only $29,000, compared to $38,000 in the U.S., and there is no merit pay (Taylor 2011). It goes to show the value placed on education and teachers in Finnish society.

In addition, the education of teachers in Finland is also very content driven. Teachers who major in education, even primary school teachers, also need to minor in at least two content areas and they study these subjects in the respective departments. For example, a teacher minoring in math will take courses in the math department (Porter-Magee 2012). Teachers also learn teaching methods that are subject-specific, rather than learning pedagogy that is considered to be one-size-fits-all (Porter-Magee 2012). There is also great emphasis on teacher improvement as they only spend 4 hours a day in the classroom and 2 hours a week on professional development (Taylor 2011).

Inclusiveness and Accessibility

Another important idea behind the Finnish education system is that it is inclusive and accessible to all. The system “has been intentionally developed towards the comprehensive model, which guarantees everybody equal opportunities in education irrespective of sex, social status, ethnic group, etc. according to the constitution” (Porter-Magee 2012). In this way, no student will fall through the cracks. One reason for this is that schooling is 100 percent publicly financed. School is free, and that includes instruction, school materials, meals, health care, dental care, commuting, special needs education and remedial teaching (FNBE 2010). This largely stems from the social-welfare culture of Finland; it is a society that values equality and the social net, even if it means high taxes.

Also, thanks to the 1970s reforms, all schools are equal. They all have the same national goals, the same national curriculum guidelines and access to the same pool of highly qualified teachers. A student also has the possibility to choose which school he or she attends as no students are selected, channeled or streamed to any particular school (FNBE 2010). “The result is that a Finnish child has a good shot at getting the same quality education no matter whether he or she lives in a rural village or a university town” (Hancock 2011). In addition, schools are small and there is a great deal of student-teacher interaction. If a student falls behind, a teacher will notice and address it, even if it is outside of class. Nearly 30 percent of children in Finland receive some kind of special help in their first nine years of schooling (Hancock 2011). This has led to a great amount of equality in education. According to a recent survey by the OECD, the differences between the weakest and strongest students are the smallest in the world (Hancock 2011).

No Standardized Testing, No Competition

The philosophy behind Finland’s education system differs greatly from the American philosophy in terms of testing and competition. Unlike the education system in the U.S., Finland does not measure students’ achievement through standardized testing and there is less emphasis on competition. Besides one exam at the end of high school, there are no mandated standardized tests. While President Obama’s Race to the Top Initiative has U.S. states competing for national funding through tests and measurements of teachers, Finland does not pressure its schools to compete. “There are no rankings, no comparisons or competition between students, schools or regions” (Hancock 2011). One of the reasons for this philosophy may be that, according to Hancock, all the actors involved in education, from national officials to local authorities, are not business people or politicians, but educators.

Nurture Outside the Classroom

Another unique aspect of Finnish education is the value that is placed on caring for children outside the classroom. Part of this may be due to the relatively high standard of living that Finns have, but steps have also been taken to assure this. Finland grants three years of maternity leave and subsidized day care to parents, including preschool, which is attended by 97 percent of all children (Hancock 2011). The government also subsidizes parents for having a child in the first place by paying them about 150 euros per month for every child under the age of 17. Children are also encouraged to live healthy lives in that they have minimal homework and spend far more time outside, even in winter. For example, elementary school students have an average of 75 minutes of recess a day, compared to 27 minutes in the U.S. (Taylor 2011).

National Guidelines, Local Flexibility

One last important concept in Finland’s education system is that, although there is a national curriculum, much is left to the local level. In this way, the national curriculum is “more of a guide than a script” and educators have broad autonomy over their school’s curriculum and instruction (Porter-Magee 2012). However, it is important to note that this was only done after decades of tight control and national reform. The state loosened its control only after standards were raised. This localization was done so that “local needs could be taken into consideration and special features of the school could be made use of” (FNBE 2010). Similar to the philosophy of being against standardized testing and competition, there is now little oversight and inspection coming from the federal government. The administration of education is entrusted to the providers of education and teachers.

Conclusion

Finland is an egalitarian society that supports every person’s right to have an equal education and opportunity to succeed. It is committed to the ideals of a welfare state and this is evident in its education system. Teachers are valued and a great amount of effort is put into their development. All schools are treated equally and no child will be left behind. Standardized testing is avoided in order to concentrate on the more human side of education. Children are nurtured outside the classroom so that they can learn and develop better in the classroom. Schools and their teachers are entrusted to do what’s right without control from the national government. These aspects of Finnish education have developed out of or have been affected by historical, cultural and philosophical influences. And they, in turn, will affect the history, culture and philosophy of Finland.

Sources:

FNBE – Finnish National Board of Education (2010). Website: http://www.oph.fi/english/education

Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. Website: http://www.minedu.fi/OPM/?lang=en

Hancock, LyNell. (2011). Why are Finland’s Schools Successful? The Smithsonian. September Issue, 2011.

Porter-Magee, Kathleen. (2012). Real Lessons from Finland: Hard Choices, Rigorously Implemented. The Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Sahlberg, Pasi. (2012). Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland? Series on School Reform. Blackstone Audio, Inc.

Sirota, David. (2011). How Finland Became an Education Leader. Salon. July Issue, 2011.

Taylor, Adam (2011). 26 Amazing Facts About Finland’s Unorthodox Education System. Business Insider, December 14, 2011.