Diversity and Access to Education

To understand the diversity and accessibility in the South Korea education system, we need to first look at some general information, especially about the overall population. From the general information, we will move on the statistics that are more associated with the education system and the specific programs are in place to address certain issues.

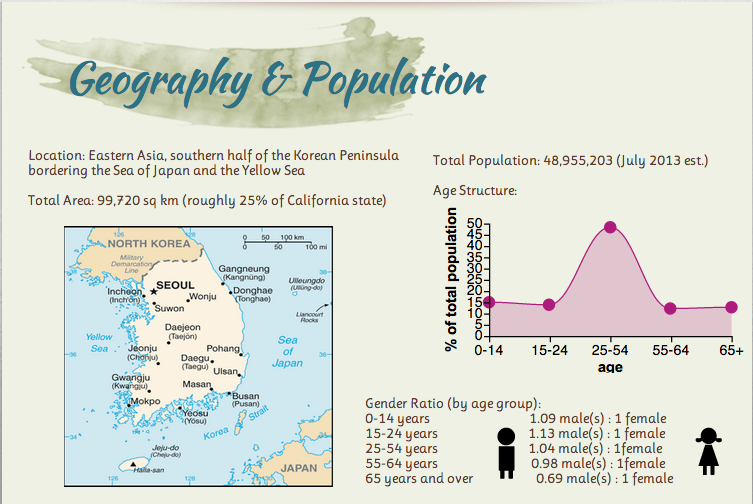

First, let’s take a look at some general information about South Korea:

South Korea is mostly surrounded by water, with North Korea as the only piece of bordering land, therefore the population is mostly homogenous. The major ethnic group is Korean, with about 20,000 ethnic Chinese Koreans. Given this homogeneity, the language spoken in South Korea is Korean although English is taught in most junior and high schools. In terms of the general population, the ratio between females and males are fairly even. The overall age groups form a bell curve, which provides the information that majority of the country’s population are working-age appropriate and the difference between the young and the old are even. This information allows us to make the assumption that South Korea is fairly protected from border conflicts with a even distribution of age groups and gender, which supports it’s current economic stability and global success.

Access to Education

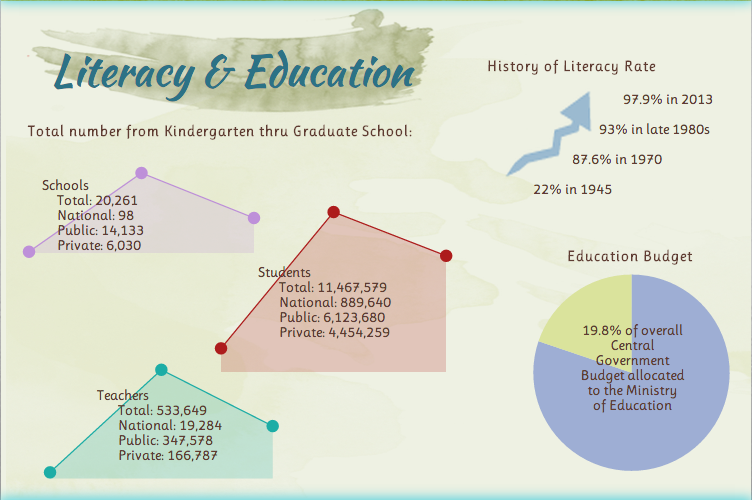

Although the population is not very diverse, this next section will give us a better picture about the accessibility of education in South Korea. Here, we have some general information about its literacy and resource allocation:

As previously mentioned in the “Historical Influences” section of this blog, the Japanese occupation (1910-1945) in South Korea devastated the quality of human resources in the country. Oppressing Koreans from receiving a comprehensive education and leaving them with huge gap in qualified teachers, the Japanese left Korea with a 78% illiteracy rate in 1945. Due to its Confucian cultural influence, Koreans highly valued education and began to work on various reforms to build up a literate population. The Basic Education Law in 1949 and then the national strategic plan with a focus on education reforms in 1962 created compulsory education for children from elementary and middle school (Sorensen, 1994). By 1970, the literacy had gone up from 22% in 1945 to 87.6%. This progress did not stop, and now Korea has a literacy rate of 97.9%; breaking this percentage down further, 99.2% of males and 96.6% of females are literate. (Note: literacy is defined as people over 15 years of age who can read and write.)

Its success in literacy and education is supported by their value-of-education cultural background. Since education is highly regarded in their culture and is perceived as the means to climb up the socio-economic ladder, the South Korean government has allocated 19.8% of the central government budget to be used on education. According to the CIA World FactBook (2013), South Korea also invests 5.1% of their $1.6 trillion GDP (approx. $81 billion) on educating their 11 billion students. Also, looking at their overall number of schools, teachers and students ratios, there is a clear consistency since all the slopes are at a relatively similar angle.

From the data above, we can see that education is quite accessible in South Korea. With the 9 years of free compulsory education system and resources poured into education, the literacy rate of this education-centered culture will remain high.

Education Trends

In the next section, we will take a look at the educational trends in South Korea and some issues that have arose in recent years:

The enrollment trends in South Korea are consistent with that of a developed country averaging at 17 years of school total. The 16 years of schooling for females are consistent with 12 years of education through high school plus 4 years of university. The 18 years of schooling for males are also consistent with the 16 years of school (similar to that of the female population) plus 2 additional years since all Korean men have mandatory 2-year military service.

In terms of accessibility, there is a 99% enrollment rate for elementary school with a 99% advancement rate to middle school. From middle school, the advancement rate to high school is at 96.6% (Ministry of Education, 2008). This means that almost 100% of the current South Korean population have access to primary and secondary education. From secondary school, 82.8% of high school graduates advance to tertiary education, while 36.5% become employed (some are employed while attending junior or vocational colleges).

However, the issue with accessibility occurs at the tertiary level. Although over 80% of students advance to colleges, only 40% of these students complete their college education. One reason for this attrition rate is because starting from high school, education is no longer free. Therefore, the financial burden becomes more intense over time. With South Korea being one of the major contributors to study aboard programs in the U.S. and the need for global learning increasing, it becomes too costly to stay in school. Another contribution to this issue is the increased hiring rate for non-degree high-school graduates. According to The Economist (2011), 18 South Korean banks have doubled their non-graduate employee intake, and multi-national corporations (like Samsung, LG, Hyundai, and SK) have reserved 30,000 jobs for non-university high-school graduates. With jobs available without a college degree, it is not uncommon to see a 60% drop-out rate in South Korea’s tertiary education system.

Immigration & Education: Increasing Diversity

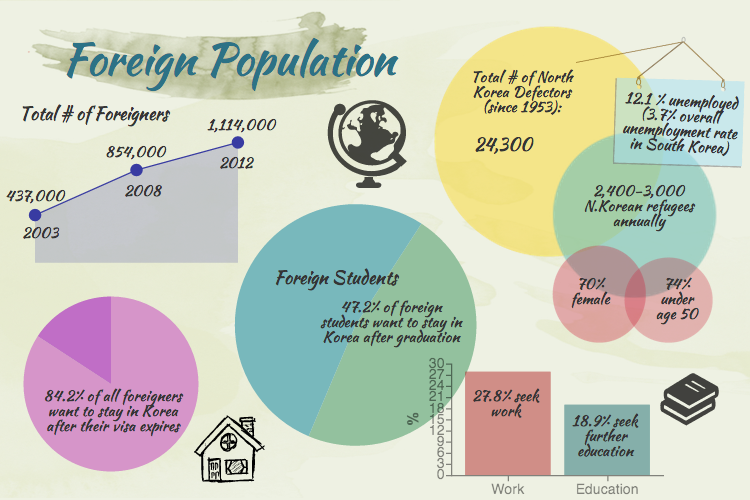

In the final section below, we will take a look at that issue of the foreign population and its effect on the education system:

As South Korea becomes more economically successful and globally recognized, it is not unfounded that the foreigners population have nearly tripled in merely 10 years time. A major contribution to the foreign population are the English teachers, multinational corporation businessmen, and North Korean defectors. According to Statistics Korea (2012), 84.2% of all foreigners in South Korea have the intention to remain in the country. 59.2% of them extend their stay, while 20.1% achieve permanent residency and 13.2% achieve South Korean citizenship. Contributing to these numbers are 47.2% of all foreign students also intend to stay in South Korea after graduation to seek work or additional education.

In addition to the increase of legal foreigners, a total of 24,300 North Korean defectors have been seeking asylum in South Korea since after the Korean War in 1953. According to Shin (2012), an average of 2,400 to 3,000 North Korean defectors illegally cross the border in hopes for a better life in South Korea. Since 70% of them are females and 74% under the age of 50, they contribute a lot to the economic fluctuation of South Korea, dependent on whether they assimilate or not. With Shin’s (2012) statistics on the North Korean unemployment rate being at 12.1% (triple the national average of 3.7%), it is clear that North Koreans are still have a hard time adjusting to the South Korean lifestyle. There are even some extreme cases at times where the defector would voluntarily return to North Korea because of their difficulty with adjustments. However, the South Koreans have not been hostile.

Various programs have been set in place for legal and illegal foreigners. As South Koreans realize that their country is becoming increasingly more diverse, “better awareness and appreciation of cultural differences can be promoted through the celebration of cultural diversity” (Kim & Kim, 2012, p. 243). Therefore, programs for adult foreigners, North Korean refugees, and a push for a multicultural curriculum for children have been put into place.

To assist the legal foreigners with assimilating to the homogeneity of South Korea, organizations like Korea4Expats are creating governmentally approved programs to educate them – Korean Immigration and Integration Program (KIIP). Although the program does not guarantee citizenship and is not required by the South Korean government, it is highy recommended that expatriates take advantage of these free courses. KIIP was designed and is implemented by the Ministry of Justice, which provides foreigners with Korean language training and classes on understanding Korean society (Korea4Expats, 2011).

For the North Korean defectors, the South Korean government has been spending about 60% of the overall governmental budget in building learning centers (Hanawon Centers) for these refugees. In 1999, the first Hanawon center was built to support the female and young refugee population. Currently, the South Korean government is building a second Hanawon center that will be larger in order to house more defectors and will also provide training for male refugees. The new Hanawon center will also offer reeducation to the upper-level graduate defectors. In these centers, North Korean defectors learn about sanitation and nutrition in order to be able to sustain on their own after their three-month stay at the centers (Shin, 2012).

Given the age group of foreigners who come to South Korea, it make sense that a lot of the support the coming from various organizations (usually governmental) to support the adaptation and assimilate for adult immigrants. However, with the increasing number of adults, there will be an increasing number of children who are not receiving additional support at school but forced to integrate through a sink-or-swim basis. Therefore, in recent year, there has been a push to provide students with a multicultural education. Although the government has implemented a Support for Multicultural Families initiative in 2006 and revised the national curriculum to include more content on cultural diversity and universal human rights, all of the focus of multiculturalism is (Kim & Kim, 2012, p. 249). In addition to this, another issue revolves around the accessibility to these support initiatives. Most of the Support for Multicultural Families facilities and schools that support the multicultural curriculum are located in urban areas. However, most of the minority groups, assimilating refugees, and new immigrants are usually located in rural areas where the cost of living is more affordable. Thus, it should be of great importance that the South Korean government discuss the issues of the growing diversity in the globalized country.

Conclusion: Diversity and Accessibility

From all the data above, it is clear that South Korea is mostly homogenous, with 97.8% of its population of Korean decent. In addition to obvious homogenous population, South Koreans “have been obsessed with the long-standing principle of ‘pure-blooded’ as a source of nation pride” (Cumings, 2005, as cited in Kim & Kim, 2012, p.248) and had always had negative stigmas associated with marriages between Koreans and non-Koreans (Kim & Kim, 2012, p. 244). This strong pride in ethnic homogeneity causes South Korea’s education system to be less diverse and all multicultural programs to extremely one-sided. But from the increasing number of foreigners entering the country and its continued upward mobility on the global economic ladder, diversity will be inevitable. The question is: How will South Korean government address this issue and how will the homogenous South Korean population perceive and adapt to this change?

In terms of the accessibility, it is clear that primary to secondary education is highly accessible. However, starting from tertiary education, there are the issues of financial ability and motivation for students to continue their tertiary education. For the support of immigrant families to the education system, there seems to be a lack of access due to the location of such educational organizations. Though literacy is and will continue to remain in the 90 percentile, this can only prove that education access is available to the 0-18 years-of-age population. Continuing education and access to adult education remains an issue that the South Korean government should address, but does not seem to take priority over at time moment.

References

CIA World Factbook. (2013, April 29). East & Southeast Asia: Korea, South. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ks.html

Cumings, B.(2005). Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History, Updated Edition. New York: W.W. Norton

D.T. (2011, November 3). Glutted with graduates. The economist. Retrieved from

http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2011/11/education-south-korea

Kim, S.K. & Kim, L.H. (2012). The need for multicultural education in South Korea. In David A. Urias (Ed.), The immigration & education nexus (pp. 243-253). Sense Publishers. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/1349438/The_Need_for_Multicultural_Education_in_South_Korea

Korea4Expats Consulting. (2011). Korean Immigration and Integration Program. Retrieved from http://www.korea4expats.com/article-social-integration-korea.html

Lee, J. (2010, February 3). Animosity against English teachers in Seoul. Global post. Retrieved from http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/south-korea/100122/english-teachers-seoul-racism?page=0,0

Ministry of Education. (2008). Statistics. Retrieved from http://english.mest.go.kr/web/1723/site/contents/en/en_0219.jsp

Mongbay. (2013). South Korea – Education. Retrieved from http://www.mongabay.com/history/south_korea/south_korea-education.html

OECD Factbook Statistics. (2013). Republic of Korea. Retrieved from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/country-statistical-profile-korea_20752288-table-kor

Shin, H.H. (2012, May 12). New resettlement center opens for N.K. defectors. The Korean Herald. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/refdaily?pass=463ef21123&id=50c041fc5

Sorensen, C.W. (1994). Success and Education in South Korea. Comparative Education Review.38:1, 10-35.

Statistics Korea. (2012). 2012 Foreigner Labour Force Survey. Retrieved from http://kostat.go.kr/portal/english/news/1/16/3/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=273073&pageNo=&rowNum=10&amSeq=&sTarget=&sTxt=