Frozen in motion in Langtang National Park

Day 1 | the journey begins

The small bazaar of Syrabru is reached by a dramatic highway precariously carved high on a steep rocky hill side, six hours north of Kathmandu by jeep (nine by bus). Long stretches of loose gravel accompanied by increased tossing in our seats indicated where the previous year’s landslides had taken their toll, making you realize how isolated the occupants must be during the monsoon season. The landscape is simply unreal. The canyon bottle-necks vertically in space, bringing the river up as the road gradually descends north into the canyon. Syrabru bazaar sits at where the road and river meet, where the pavement ends: a dusty, nondescript market town with two faces. To the trekker, it represents the end of the road, the end of civilization, the end of telecommunications; the place one fully leaves her cares behind in order to begin a fresh journey. But to the local, it represents the center of resources – of vital supplies and services: household goods, clothing, fruit, education, transportation. It is a place of necessity, a place one goes when in need of mundane items, or in need to reach the capital. Thus Syrabru simultaneously represents necessity and freedom. It is the beginning and the end. It is both mundane and exotic.

My friends (Justin and Rachel) and I couldn’t help but ponder such things as we passed through Syrabru to begin our journey. We wondered: how strange must we look to these villagers, voluntarily hauling stuff through their yak-pastures in the name of leisure and adventure? What, I wonder now, does the notion of adventure even mean to them? What would the equivalent spectacle be for us, were we home? The best we could come up with were those bus loads of Japanese tourists who hop out in front of every miniscule monuments to have their photo snapped waving peace signs and wearing strange grins of satisfaction. They, perhaps, seem as ridiculous to us (urban dwelling Americans) as we must look to these Nepalis. Perhaps.

Syrabru is the gateway into the Langtang Valley; locals and visitors alike must enter by foot and follow the river up a narrow rocky path. Our first day’s hike began in the afternoon following the long jeep ride and was thus limited to a couple hours. So when we came upon the “town” Pairo squeezed precariously in a narrow stretch of canyon we decided to call it home for the night. To call it a town is not only false but overly generous, as it consisted of two lodges in it’s entirety. Our room was precisely seven by twelve feet, just big enough for one double bed, one twin bed and the space to walk between. The walls of the dining hall were made of windows, overlooking the river canyon below, lined with benches and narrow tables so that all occupants could enjoy the faint heat from a tiny stove built into the middle. Cozy indeed.

Day 2 | rest and reflection

Despite a long and restful nights sleep, Justin awoke with a strong and persistent nausea – nausea that left him upon throwing up but promptly returned upon the consumption of anything whatsoever. Thus we decided to spend the day in Pairo to wait things out in hopes that his stomach would improve with time. In the afternoon, between vomit sessions, we all played cards on a table outside. Across the canyon we noticed a troop of langer monkeys – at least two dozen hopping between trees, perching to pick fruit or leaf sprouts for intervals. Langur monkeys have black-skinned faces surrounded by white fur, with white bellies, gray bodies, and impressively long tails. Sitting squat in the trees and viewed from a distance, one may guess them to be the size of a medium-small dog. But when they’d hop down and bound across the forest floor their bodies stretched out to full size, and I was surprised – they’re so big! The size of a large dog, or a ten year old child even. Between hands of cards my eyes drifted to stare at them in wonder. We chose to sit outside in hopes of catching the sun, which eventually did reach us but very promptly disappeared a behind another ridge. In the winter the lodge must only get 15 minutes of direct sunlight each day.

The time spent sitting at a lodge provided an interesting glimpse into the life of a lodge keeper, and another opportunity to reflect on perspective. Lodge towns are one of two things to a trekker: simply a part of the trail where one takes tea and a short rest, or a node – a destination for food and sleep for the night. The trekker sees many of the same characters along the trail, but the setting and lodges are always changing. For the lodge keeper, the setting is consistent, but the cast of characters change – everyone comes to them. The day is a steady rhythm of household chores – making the fire, making breakfast food, making lunch food, making tea, washing mounds of dishes, cooking food and washing dishes again, doing laundry, setting up and taking down the souvenirs. A rhythm of services.

Per the guide book and the adjacent Tamang Heritage trail, I expected the people along the route to be predominately of Tamang ancestry. But I was wrong. At one point during the day as Rachel and I cozied up beside the kitchen fire, a group of three locals stopped in for tea. The woman wore a Tibet-style striped apron and had large gold and turquoise looped earrings, apparently so heavy that they required a string tied across the back of her head to help hold them up. I listened intently, but did not understand what they were saying. So I inquired, “Are you speaking Tamang?” To which the keeper, a young woman, told me, “No. We’re speaking Tibetan.” The keeper was 23 years old. Apparently Tibetan was her second language; her first: Hilambu-Sherpa. From there on out, we continued to meet lodge keepers of Tibetan or Hilambu-Sherpan orgin, and Rachel’s Hindi – something that had impressed many store keepers and service people in Kathmandu, a language understood by the majority of Nepali people I meet – was understood by almost no one.

Day 3 | signs and stars

Luck was in our favor and Justin awoke free of nausea the next morning meaning we could move forward with our hike as planned. Unfortunately though, having not eaten anything the day before he had little expendable energy. Patience became the theme of the day. And I genuinely believe we achieved a sense of true patience among each other. We practiced hiking without ego – hiking for the joy of it rather than for the prize destination at a set speed.

The days hike was a steady climb following the river canyon upstream. The trail had to gain equal or more elevation than the river at all times. That’s easy on a plain, but in a steep mountain valley it meant climbing 1100m in around 6 hours. Constantly, steadily climbing. The last stretch was a real push, but well worth it. At the top of the longest, steepest climb, I spotted prayer flags – a beacon of hope. On Nepal treks, prayer flags mark the top of a climb and a developed resting place – usually a small stone bench built at the base of a shade tree. Thus the site of prayer flags along the trail provide confidence and motivation to the knowing trekker. They tell you: you’re almost there, rest awaits you. They are a signal unique to this place and something I will miss when hiking in the US (perhaps I’ll bring loads back with me to place atop all the climbs around California hiking trails….).

We reached Ghodatabela just before sun set, painting the mountains a rich warm pink. Ghoda means horse in Tibetan, tabela means stable, so sure enough this was the first place we saw horses. Sturdy, thick-coated horses. And it was the first town above the oak tree line; a small pine forest spread on the south side of the river, but the north side consisted of limited vegetation. Once again “town” is generous – the place consists of two guest houses, their keepers and three horses.

This lodge had a detached restroom, so I found myself outside beneath the stars before bed. They sparkled twinkling and bright, so very bright above the mountains. A few stars kissed the snow covered ridge to the north. I forgot the cold, losing myself in the beauty above.

Day 4 | a buddhist valley

With a shorter day and slightly less elevation gain ahead of us, we began the day in good spirits despite a fitful night’s rest. It had been quite cold, our lodge poorly insulated (numerous half inch gaps in the plywood invited the cold winds inside). In the bathroom water basin, a thick layer of ice had formed overnight. Today was the day we’d set to reach Kyanjin Gompa, the uppermost lodge-town that sits beneath Langtang Glacier.

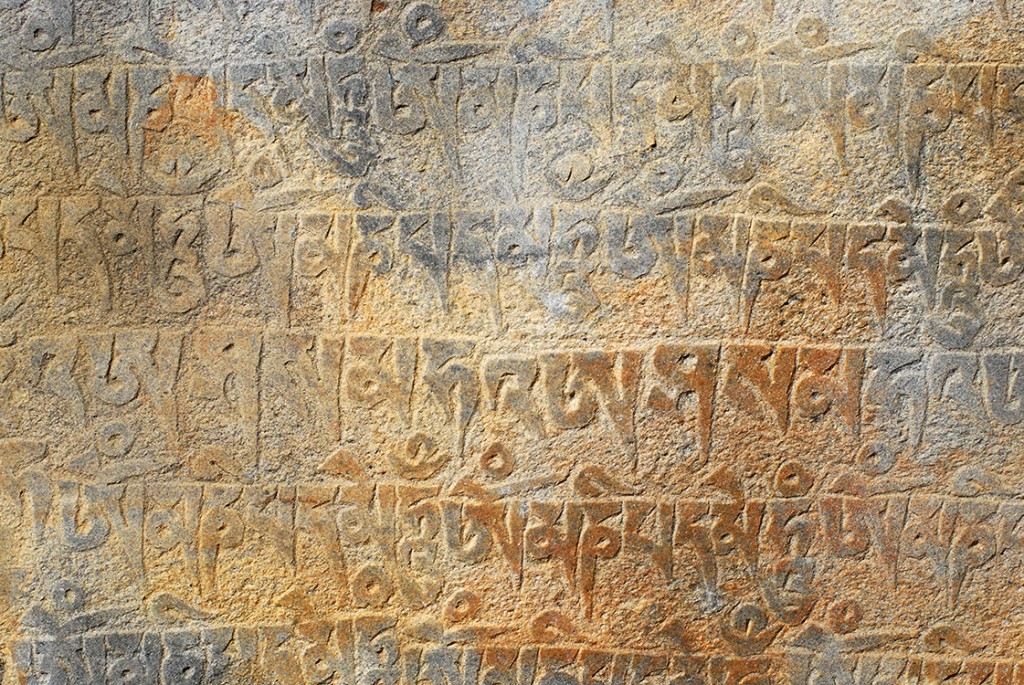

As we hiked up the glacial valley in the shadow of the steep southern ridge, we carefully picked our way across numerous half-frozen streams. Every visible stream on the southern ridge appeared frozen solid. The waterfalls on the northern ridge still flowed, but with icy statues growing beneath. Many stretches of path were lined with long mani walls, some nearly a mile, walls made of carefully stacked, carved stone. Most had the mantra “om mani padme hum” carved over and over again in tibetan script, the same phrase written on prayer wheels and prayer flags. But some also had lotus flowers or meditating buddhas. All had paths on either side and instructed the walker to please stay to the left – to circumnavigate the walls in a clockwise direction. We were clearly in a land where Buddha was worshiped, not Lord Shiva – although over a pass immediately south there was a lake said to be created by Lord Shiva, which is thus the site of annual Hindu pilgrimage for many devotees. Religious overlap and tolerant coexistence has become a definitive characteristic of Nepal in my mind.

The valley dead ends on several glaciers, ringed by 7000m mountain peaks – a natural geo-political border today, a natural migration boundary for centuries. What ever made people wander up this harsh, high-altitude valley and settle? Through Syrabru to the west, a dirt road continues north into Tibet – a historic trade route China has eyes on developing in the future. Accordingly to folklore, many centuries ago aTibetan yak herder passing along the route into Tibet lost track of one of his herd at Syrabru. The yak wandered up and up and up the deep river valley to the east and the herder chased after it. When the herder finally caught upa few days later they had reached a deep glacial basin around 3900m high, surrounded by peaks and glaciers 7000m high, the location of Kyanjin Gompa today. He killed the yak a couple kilometers farther up the canyon and used his blood to paint a giant boulder red. In Tibetan, the word lang means yak, and teng (dhang) means to follow.Thus the name Langtang valley. Yaks remain prevalent today, grazing the pastures along either side of the trail above 3000m. Most lodges offer dishes with yak-cheese, and apparently there’s a large yak-cheese factory in Kyanjin gompa at the top. (We were told it was closed for the season).

The only other locally produced product of evidence was seabuckthorn juice. Through several lodge-towns signs advertised fresh seabuckthorn juice. I was already familiar with the strange fruit from my trips into lower mustang, but I had never seen it on the tree before. In this landscape, in this frozen climate, I thought to myself, how could fruit possible prosper? As the question floated in my head, we turned a corner and – there it was. Seabuckthorn trees, in want of leaves but absolutely covered in bright orange berries.

Day 5 | a view to the heavens

Rachel and I awoke to a view of the sun slowly setting the glacial basin aglow. Happy and appreciative of our surroundings and in no rush, we decided to spend the morning climbing to a view point another 700 meters above the lodge. The trail was steep and slick, the altitude sat heavily on our lungs. Each time we’d rest to catch our breath, we’d look down in wonder at how much smaller the lodge town had become and at how broadly the valley view opened up to us. We soaked in the beauty with every trying step until we finally reached the rocky, prayer-flag draped peak. Such glory, such wonder. The deep valley we’d spent the past two days climbing appeared a mere slit in the surrounding ring of mountains. The sun twinkled merrily above the Ganja-la range to the south while clouds formed and dispersed off the snowy face of Langtang Lirung to the north-west. Below Lirung the landscape was roughly carved in the distinct path of a glacier. East of the lodge village, an icy river spread its fingers across a gravelly valley bottom. I am among the people who can sit in such a place for hours, staring at the landscape around me with contented wonder. What is it that makes such places so sacred? Why do they bring me such internal peace? I may never truly know. As we picked our way down, careful not to slide, I paused many times to remind myself: I am in Nepal, I am exploring the Himalayan mountains; life is beautiful and sweet; I am fortunate. I’d close my eyes to soak up the wind and sound, and reopen them to soak up the grand landscape afresh. Appreciation. Appreciation.

Fresh off the slopes, high from the surroundings, we began the part of the journey least looked forward to: the return, the turn around – the beginning of the end. Even while the journey was not yet complete, the sense that it will be over all too soon sat heavily on each of us as we silently began the hike back down the steep canyon. We wanted more, and luckily we had more ahead of us.

Day 6 | the road less traveled

Mid-day, we reached a fork in the trail that presented us with an intriguing option: one trail veered to the left, continuing the steep plummet into the narrow canyon from which we came; but another trail veered to the right, hugging the north ridge high above the river bottom. It meant more climbing and a tighter schedule for the following day, but we are not the type to resist the temptation of fresh territory to explore. So to the right we went.

The difference in trail was immediate: more narrow, less used and thus less maintained, and lacking any other travellers. It reminded me of the short-cut trails I use to visit village farmers’ groups at my post. About a half hour in we ran into another troop of langur monkeys and we decided to see what would happen if we just stood still. The monkeys held their alert poises for about five minutes, then, finding us either unthreatening or uninteresting, carried on with what they had probably been doing before: relaxing in the trees picking at the fresh buds and fruit. Even having been here, in this country where monkeys are a part of daily life for many and almost universally considered a pest by the locals, I remain fascinated by them. Every time I am reminded and astonished by how very truly human they are – their hands, their mannerisms. In another life I certainly could have been a Jane Goodall…

The trail continued up, wrapping around a corner to reveal perhaps the most precarious bit of trail we’d yet seen. Trail literally carved into an 80 degree slope, meticulously reinforced with stacked stone. It was certainly sturdy enough to cross, but we couldn’t help but laugh among ourselves and ask – who would go through all this effort to build a trail here? The town we were shooting for would be the first human habitation along the route, and it would surely be easier to reach it from Syrabru. It was simply one of those moments one stares in wonder at the work of man.

As twilight began to fall, we turned a final ridge corner to find Sherpagaun – our resting village for the night, a village that consisted of approximately 9 households, 25 occupants, perhaps 25 cows, and a lot of narrow terraced fields carved into the slope. Justin couldn’t help but ask aloud: what made people decide to settle here? On this steep slope, several hours hike from other villages, several hours hike from the river? I answered: inheritance? At this point I suppose the inhabitants remain out of inertia, inertia and the fresh economic opportunity presented by trekkers. But ask them why their ancestors settled here and I’m guessing most would not be able to answer.

Day 7 | out and in

We spent our final morning hiking up the ridge along another steep cliff-side trail for about an hour before steeply descending through a pine forest into another small hillside village. I soaked up the smell of pine with a contented grin. Pine is the smell of home, the smell of northern California, and will be forever comforting. In the interest of time we took the most direct trail down to the river possible, which turned out to be an endless switchback thorough forest and fields of tall grass. Downward, downward, downward. Turning, turning, turning. Toes aching, knees shaking. The wind roaring up the canyon, singing through the trees. We’d turned a corner of the ridge to aline with the north-south canyon that leads into Tibet. All wind pushed north into Tibet. Dust swirled, grass pointed in exaggerated desperation: “Go that way,” it pleaded. But south we continued. Despite all sense of progress, there was always more – the trail continued down, down, down, 1000 meters continuously down. Down until we finally reached somebody’s field and were able to follow it across, gradually down even more, down until we hit bottom: the suspension bridge. We crossed a surreal azzurro blue river, surreal with it’s vivid bright blueness, and climbed back up into civilization. From frozen glacier to glacial melt, our trekking journey finally met its end.

Our jeep awaited us in the Syrabru. Pavement. Roadway. Fresh sensations. Fresh shock of development, of concrete and motorcycles and cheap plastic household supplies. We departed mid afternoon for the second, longer half of our days journey – the road back to Kathmandu. Fresh motion sickness. More ginger chews. More bumps and twists and turns and near misses with bursting buses – so full that their roof tops were laden with riders, legs swaying back and forth with the rocky vehicle as it clambered over the rough terrain. After a quick tea break at the supposed half-way point, we turned up a new road – another, somehow narrower, windy canyon road. It seemed to climb gently yet steadily from the beginning, and yet around every ridge the next ridge was somehow higher, the road forced to wrap up and around again and again and again, our hopes and intuition completely confuddled. It seemed to take hours, darkness falling around us, pink disappearing from the distant mountain peaks, before we at long last breached the top. And then – the hoped for vision of Kathmandu below was in fact, impossibly, far in the distance. A long, long windy ride down the ridge, in and out of ravines, seemingly endless once again. If I hadn’t had a watch, no one would have believed we reached the city at 7 pm. It felt well passed midnight. All sense of time had left us.

An epic finish to an epic journey.

Very cool story