Our visit to the Salinas Valley State Prison was an inundation of experiences and emotions. Toward the end of our time there, we were in the yard that housed some of the most active members of the gangs that fill the prisons, which is consequently one of the most regimented yards. Each gang controls certain parameters, and our guide explained that there has been bloodshed over determining who owns which territory. As the inmates were released in a controlled fashion, they circled the inside track and found their places at a cement picnic table or against the back wall, where they posted themselves to quietly survey the scene. Presumably this continues for the duration of their time outside their cells for the day. Our guide brought up the need to belong, and also how everyone there feels a sense of fear. The inmates fear what terrifying consequences will occur at the hands of other gang members if they make the smallest mistake, and they also fear leaving the gang, because it could cause them to lose this sense of belonging, their identity, and the group that has become family. Our guide described that when some previous gang members step down, they may be traumatized and lose their sense of direction and role. The corrections officers are also fearful — that an event will set off violence, that they won’t be able to control it, that someone or themselves will be badly injured. Everyone in the yard has an underlying fear that something awful will happen, but instead of being able to express that fear, it must be masked by a façade of toughness.

Our visit to the Salinas Valley State Prison was an inundation of experiences and emotions. Toward the end of our time there, we were in the yard that housed some of the most active members of the gangs that fill the prisons, which is consequently one of the most regimented yards. Each gang controls certain parameters, and our guide explained that there has been bloodshed over determining who owns which territory. As the inmates were released in a controlled fashion, they circled the inside track and found their places at a cement picnic table or against the back wall, where they posted themselves to quietly survey the scene. Presumably this continues for the duration of their time outside their cells for the day. Our guide brought up the need to belong, and also how everyone there feels a sense of fear. The inmates fear what terrifying consequences will occur at the hands of other gang members if they make the smallest mistake, and they also fear leaving the gang, because it could cause them to lose this sense of belonging, their identity, and the group that has become family. Our guide described that when some previous gang members step down, they may be traumatized and lose their sense of direction and role. The corrections officers are also fearful — that an event will set off violence, that they won’t be able to control it, that someone or themselves will be badly injured. Everyone in the yard has an underlying fear that something awful will happen, but instead of being able to express that fear, it must be masked by a façade of toughness.

There was an eerie sense in the yard, very measured interaction, a careful line that everyone is walking in order to maintain “getting along.” Pushpa pointed out that it was sad – especially how the northern gang was acting. They had virtually no interaction with one another. They were standing still against the back concrete wall, arms crossed, vehemently performing their assigned role in the gang, which they would continue for hours. We’re all seeking to have a role and a purpose, but for the inmates, this is where their need for belonging and purpose brought them — to the corner of a cement enclosure, where their role has become to protect their piece of the yard. But this need to belong also had very real consequences for others while these inmates were in society. It made me wonder, what makes it possible for individuals to change for the better? For these prisoners, whose role is now so deeply engrained, what can lead to the psychological shift that allows change to happen? Is it time, or events, or a particular piece of learning, that can cause the need to belong to shift to incorporate different priorities?

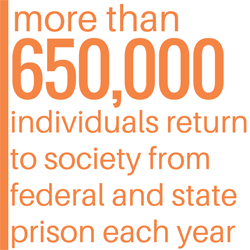

Just half an hour later, we found ourselves sitting in on a group session of substance abuse prevention at the Correctional Training Facility. The group was discussing their values — what is most important to them in their relationships, physical environment, intellectual growth, and emotional growth. The men in the group were so open, thoughtful, and expressed great clarity about their priorities. It was an inspiring community. Everyone that was participating seemed both eager and realistic. They embraced that they will face very real challenges when they return home…temptations to return to an old lifestyle and to fall into previous patterns, but also a belief that they can be true to the relationships they deeply value, and who they have come to understand themselves to be. Feeling the energy in the room made me feel hopeful, but it also made me concerned as to whether society is ready to accept their personal changes. I hoped that the incredible resilience and strength that they showed in that room will carry over when they face another unimaginable challenge — the stigma and expectations associated with those that have been incarcerated. How will they find a job, and housing for themselves and their families? Our systems are not set up to support individuals who are not the same as when they became incarcerated. It made me want to learn a great deal more about how those with records go about navigating society, if they are able to do the hard work on themselves in order to be released. The post-prison system is one of our nations most broken systems, as ex-offenders are likely to fail because the system predominately sets them up to do so. As options for parole become more prevalent, and the culture of rehabilitation is returning to the prison system, how is that matched by employer practices? How can community views of the previously incarcerated population transform, to reflect an understanding of how those individuals have also changed?

Just half an hour later, we found ourselves sitting in on a group session of substance abuse prevention at the Correctional Training Facility. The group was discussing their values — what is most important to them in their relationships, physical environment, intellectual growth, and emotional growth. The men in the group were so open, thoughtful, and expressed great clarity about their priorities. It was an inspiring community. Everyone that was participating seemed both eager and realistic. They embraced that they will face very real challenges when they return home…temptations to return to an old lifestyle and to fall into previous patterns, but also a belief that they can be true to the relationships they deeply value, and who they have come to understand themselves to be. Feeling the energy in the room made me feel hopeful, but it also made me concerned as to whether society is ready to accept their personal changes. I hoped that the incredible resilience and strength that they showed in that room will carry over when they face another unimaginable challenge — the stigma and expectations associated with those that have been incarcerated. How will they find a job, and housing for themselves and their families? Our systems are not set up to support individuals who are not the same as when they became incarcerated. It made me want to learn a great deal more about how those with records go about navigating society, if they are able to do the hard work on themselves in order to be released. The post-prison system is one of our nations most broken systems, as ex-offenders are likely to fail because the system predominately sets them up to do so. As options for parole become more prevalent, and the culture of rehabilitation is returning to the prison system, how is that matched by employer practices? How can community views of the previously incarcerated population transform, to reflect an understanding of how those individuals have also changed?

After the visits, Julie, who is a journalist that focuses on crime reporting, talked to us about sentencing practices. She had just told us about a juvenile that was sentenced to 65 years for being involved in a crime where a murder occurred, although he didn’t pull the trigger. I asked her about her opinion of the fairness of sentencing, especially in relation to drug charges, and the degree to which this might have impacted the inmates of SVSP and the CTF today. She pointed out that this is something that the incarcerated community does not have the privilege of questioning – due to their circumstances it could destroy one psychologically to spend their days in prison thinking about how their sentence could be predominately tied to their race. She discussed how this is the role and opportunity of the journalist community and those that are not part of the incarcerated population — to question these policies and seek to expose realities. It was a reminder of the opportunity we have to be able to think critically about issues such as sentencing, and due to these privileges we have a duty to productively share what we learn.

After the visits, Julie, who is a journalist that focuses on crime reporting, talked to us about sentencing practices. She had just told us about a juvenile that was sentenced to 65 years for being involved in a crime where a murder occurred, although he didn’t pull the trigger. I asked her about her opinion of the fairness of sentencing, especially in relation to drug charges, and the degree to which this might have impacted the inmates of SVSP and the CTF today. She pointed out that this is something that the incarcerated community does not have the privilege of questioning – due to their circumstances it could destroy one psychologically to spend their days in prison thinking about how their sentence could be predominately tied to their race. She discussed how this is the role and opportunity of the journalist community and those that are not part of the incarcerated population — to question these policies and seek to expose realities. It was a reminder of the opportunity we have to be able to think critically about issues such as sentencing, and due to these privileges we have a duty to productively share what we learn.