Our final session was interacting with Fambul Tok, a program in Sierra Leone that looked to reduce conflict between civil war actors in the war torn country. The entire session was very emotionally heavy as we saw videos and heard stories of children being flung around and smashed into the ground, of girls being raped by family members, of children killing their parents and loved ones. For me, this really upset me as the actions partaken by the people in the country directly went against some of my prime core values, and I couldn’t understand how even though these actions were taken place, and the peace process showed community members coming together, how almost easy it seemed for forgiveness and then amicability moments after was possible.

What really struck me about this session was the role play we had enduring the afternoon. We were assigned roles within a region in the country that had a history of conflict between two groups and had to develop action plans and coordinate with our various adjacents and subordinates regarding partnership and actions. What struck me during the presentation was the level of abosolute disconnect between us at the top, and those at the community level who were being affected by our designs and projects. There was no communication between the community groups and the national organizations, and a lot of our actions were built off the scripts we were given and not the actual needs of the people. What happened were plans developed that did not match their needs and would cause them more harm than they would good.

A lot of this mirrored the way real world peacebuilding and development can go. The lack of inclusion between local communities, the in pouring of top-down approaches within a country or region seen needed the most help, and the disconnect even between adjacents in terms of what was provided, true roles enacted by the organizations. It was a real eye opener for me to be careful of falling into the trap that development and donor dependency usually fosters, and causing more harm to communities that I intend to serve. As I continue my journey into peacebuilding, I must constantly be aware of this and try my best to be mindful of the community’s needs and desires by asking the community themselves and not assessing based off a case study – that to me is how agency will be best cultivated.

On Thursday our cohort took a trip out to the organic farming company Earthbound Farms; our trip consisted of lunch in the patio and a tour of the garden and farm and a conversation with the director and CEO of Earthbound about the business’ history, legacy, and role in relation to peace building and environmental justice. The area was impressive – thriving herb gardens and lines of delicious berries, towering sunflowers and reflective stone mazes, the rich stories of how Earthbound had contributed to community health and the farming ‘industry’ as a whole – Earthbound was an impressive example of how organic farming could contribute to the beauty and development of a community.

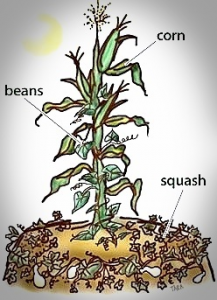

On Thursday our cohort took a trip out to the organic farming company Earthbound Farms; our trip consisted of lunch in the patio and a tour of the garden and farm and a conversation with the director and CEO of Earthbound about the business’ history, legacy, and role in relation to peace building and environmental justice. The area was impressive – thriving herb gardens and lines of delicious berries, towering sunflowers and reflective stone mazes, the rich stories of how Earthbound had contributed to community health and the farming ‘industry’ as a whole – Earthbound was an impressive example of how organic farming could contribute to the beauty and development of a community. The Three Sisters in many indigenous Turtle Island societies was the foundation of culture and world view; the “three sisters” – beans, corn, and squash – are the literal agricultural staples of Turtle Island and each crop relies on depends on the other and the environment for survival. The beans rely on the corn for support, corn relies on the squash for mulch, and both rely on the beans for restoring the soil. As the Three Sisters were being presented in the garden I stood there in awe at the fact that these crops were the embodiment of local knowledge and power it could have in helping bring communities together. Indigenous communities spent centuries diversifying and domesticating these crops, a science that is rooted in local knowledge and history, to provide foods that provided sustenance to a community sustainably. As we continued I realized there was so much local knowledge here waiting to be tapped into. Each herb and crop in that garden had more than one use, and most had alternative uses that I didn’t even know about! It really drove home the point that if organizations and communities invest more in identifying and inventorying local knowledge and processes and utilized those processes into programs and activities that there might be a change in attitudes toward local identity and self-worth but also a change in the way community members view and treat each other. Bringing programs that shoMP communities that organic farming is 1) affordable, 2) accessible, and 3) not entirely alien to food practices that many cultures already have could have a transformative effect on MP social conditions and benefit the “Feed the World” mission by first “Feeding the Home”.

The Three Sisters in many indigenous Turtle Island societies was the foundation of culture and world view; the “three sisters” – beans, corn, and squash – are the literal agricultural staples of Turtle Island and each crop relies on depends on the other and the environment for survival. The beans rely on the corn for support, corn relies on the squash for mulch, and both rely on the beans for restoring the soil. As the Three Sisters were being presented in the garden I stood there in awe at the fact that these crops were the embodiment of local knowledge and power it could have in helping bring communities together. Indigenous communities spent centuries diversifying and domesticating these crops, a science that is rooted in local knowledge and history, to provide foods that provided sustenance to a community sustainably. As we continued I realized there was so much local knowledge here waiting to be tapped into. Each herb and crop in that garden had more than one use, and most had alternative uses that I didn’t even know about! It really drove home the point that if organizations and communities invest more in identifying and inventorying local knowledge and processes and utilized those processes into programs and activities that there might be a change in attitudes toward local identity and self-worth but also a change in the way community members view and treat each other. Bringing programs that shoMP communities that organic farming is 1) affordable, 2) accessible, and 3) not entirely alien to food practices that many cultures already have could have a transformative effect on MP social conditions and benefit the “Feed the World” mission by first “Feeding the Home”.