Diversity and Equity in Costa Rica

Educational History

When the economy of Costa Rica took a plunge in the 1980s, educational services and resources suffered throughout the country, including grants, school meals and educational facilities (National Inform).

Costa Rica’s most prominent problems included a high rate of repetition in the first year of primary school, a high dropout rate in secondary school, a lack of teacher training (19 percent of teachers have no degree), and a general lack of funding for teachers (41 percent of the country’s primary schools have just one teacher for all grade levels) (Munoz).

Realizing the educational decline, the government has recently spearheaded major reforms intended to close the educational gap between public and private education and between regions, both rural and urban.

Some of the main advances include “new provision to improve the quality of state education; the implementation of a Strategic Plan (1998-2002) to improve quality, coverage and continuance in the education system and an amendment to Article 78 of the Political Constitution assigning 6% of the gross domestic product to education, including higher education” (Munoz).

These new goals reflect Costa Rican ideal of being a democratic, peaceful, and fair nation. Furthermore, the National Plan of Development has a general objective “to improve the conditions of life of the Costa Rican, by means of the attainment of the best conditions of justness, solidarity and social integration…” (Ministerio de Educación Pública)

Justness in the Curricular Development

At curriculum level, a series of programs exist that ensure access to educational services to the whole population, in particular to the most vulnerable populations. These programs include:

1. Program of Special Education

2. Program of Indigenous Education

3. Program of Justness of Gender

4. Social Policy in the Classroom

1. Special Education

Costa Rica’s economic problems have slowed efforts to protect the human rights of people with disabilities. According to the Ombudsman’s Office, the population with disabilities is among the most excluded sectors of Costa Rican society. Although laws are in place to protect disabled persons, “broadly speaking, the government does not create the necessary conditions for most persons with disabilities in Costa Rica to fully exercise their citizenship rights” (IDEAnet).

A recent report by the Ministry of Public Education’s Department of Special Education offered an overview of education for persons with disabilities. Students with special educational needs comprise about 10.13% of the total number of students. Thus, out of a student population of 937,154, there are approximately 95,000 students with disabilities. The majority are taught in mainstream classrooms, but some are taught in special classes or special schools.

Even though progress has been made in access to education for youth with disabilities, most schools are not readily accessible. The National Development Plan for 2002-2006 indicates that only 18% of all educational centers are minimally accessible; for example, having ramps both at entrances and inside buildings and accessible toilets. Even more of an issue is the many primary and secondary school teachers who tend to demean and discriminate against students with disabilities. In an attempt to eliminate discriminatory attitudes, the MEP has begun efforts to train teachers on disability issues. The National Resource Center for Educational Inclusion (CNRIE) was established in April 2002 with this aim (IDEAnet).

2. Immigration, Emigration, and Indigenous Education

Costa Rica’s emigration rate is quite low compared to other Latin American countries; only 3% of the country’s people live in another country as immigrants. The main destination countries are the United States, Spain, Mexico and other Central American countries. In 2005, there were 127,061 Costa Ricans living in another country as immigrants.

Conversely, Costa Rica’s immigration is among the largest in the Caribbean Basin. Immigrants in Costa Rica represent about 10.2% of the Costa Rican population. The main countries of origin are Nicaragua, Columbia, United States and El Salvador. In 2005, there were 440,957 people in the country living as immigrants. However, according to native sources, these immigrants tend to separate themselves from the mainstream population of Costa Rica, establishing their own communities in the country.

Take for example, an interview with Elias Maxera, a Costa Rican native and former student in San Jose. Maxera studied at a large, private Methodist high school, which he recalled as having “a guy from the U.S., but he was…just on exchange – and two girls from Peru. It was almost all Costa Rican.”

Furthermore, Costa Rica is a well known environmental touristic destination. International students come to study in science programs, which are relatively closed to Costa Ricans due to the high cost and ‘foreigner-based’ curriculum.

3. Justness of Gender

In 1984, Costa Rica ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which was the first of several initiatives “aimed at eliminating sexist stereotypes and practices that legitimize gender inequalities in the education system” (Ministerio de Educación Pública). Furthermore, the 1990 Act for promoting the Social Equality of Women made the central government and educational institutions responsible for guaranteeing equal opportunities for men and women, not only in terms of access to education, but also in terms of the quality of education. To ensure that these policies were followed, the Gender Equity Office in the Ministry of Public Education was created in 2000, and a Strategic Plan was defined. As a result, the educational status of women has improved significantly in the past twenty years.

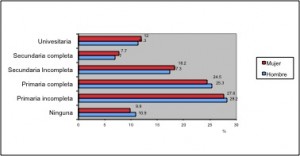

The graph below shows how women are now reaching similar, if not higher levels of education than their male counterparts.

Costa Rica: Breakdown of the population by level of education

according to gender. 2000

Source: National Institute of Statistics and Censuses, 2001.

In 1992, 50.03% of women completed primary education, rising slightly to 50.32% in 1994. By contrast, 49.97% of men completed primary schooling in 1992, falling to 48.68% two years later.

Further progress has been made since 1996, when policies were created to curtail gender or any other type of discrimination from the education system. These relate to teaching methods and materials, the decision-making structure and administration of the education system, as well as educational access and continuance for women from rural areas and marginalized urban areas, teenage mothers, etc. For added support in their education, women have equal access to a variety of grants and financial aid.

Social Policy:

Economic class:

According to the Costa Rican Constitution, “Primary education and general basic education are compulsory. Though the system is said to be free, many cannot afford the required uniforms and rural schools have no books for students.” Furthermore, the length of time daily spent in school is 3.5 hours since the school class schedule is divided into two sessions in order to accommodate the students (Private Schools spend from 7 to 9 hours in the school).

Additionally, the Constitution dictates, “The State shall facilitate the pursuit of higher studies by persons who lack monetary resources. The Ministry of Public Education, through the organization established by law, shall be in charge of awarding scholarships and assistance.” However, according to Maxera, “If you have resources you would send your kids to a private school because it’s much better. They will learn a second language, usually English. But in the public high school with few exceptions they teach you really bad English, so you can’t really talk or write, and other courses are bad because they don’t have enough funding.”

Rural vs. urban

Costa Rica’s capital, San Jose, is the hub of educational resources for the country. The central valley, in which 60 percent of Costa Ricans live, houses the four main universities of Costa Rica. According to Elias Maxera, there are campuses in other rural areas but “the quality is not the same. They offer few careers. The main region has the best primary and secondary schools”.

Indeed an ‘urban privilege’ does exist in Costa Rica with regard to access and quality of education. Although certain resources, such as telesecondario, exist, much more work is needed to integrate rural areas into the mainstream school system.

This blog post was created with information from the following resources:

Costa Rica Constitution, Article 78.

“Demographics of Costa Rica – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.”Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 May 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demograph_of_Costa_Rica

“Education in Costa Rica: An Overview..” ERIC – World’s largest digital library of education literature. N.p., n.d. Web. 2 May 2013. <http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/search/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED248570&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=no&accno=ED248570>

IDEAnet – Disability Rights Community >> International Disability Rights Monitor (IDRM) Publications >> – IDRM – Costa Rica 2004.” IDEAnet – Home Page . N.p., n.d. Web. 10 May 2013. <http://www.ideanet.org/content.cfm?id=5358&searchIT=1>.

Maxera, Elias. Personal interview. 12 Feb. 2013.

Ministerio de Educación Pública. (2002). Repetición en el Sistema Educativo Costarricense, 2002. San José, Costa Rica: División de Planeamiento y Desarrollo Educativo, Departamento de Estadística.

Munoz, Nefer. “UNESCO – Education for All – Knowledge sharing – Grassroots stories – Caribbean.” United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 May 2013. <http://www.unesco.org/education/efa/k

National Inform:The Development of Education, Costa Rica.” Ministerio de Educación Pública: División de Planeamiento y Desarrollo Educativo, Departamento Planes y Programas. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 May 2013. <www.ibe.unesco.org/International/ICE47/English/Natreps/reports/costarica_en.pdf>.