Home » Articles posted by Hinda Majri

Author Archives: Hinda Majri

How Senegalese Girls Benefit from Access to Single Sex Sanitation Facilities

Considerations

Basic accommodations such as hot showers, access to flushing indoor toilets, and the availability of restrooms in schools can be easily taken for granted. Having intrinsic needs met reduces stress, worries and fears. Access to adequate water and sanitation facilities is crucial for school children to avoid the risks of illnesses which may cause them to be absent. Single sex facilities are especially important for girls who are at a higher risk of missing school if menstrual hygiene cannot be practiced.

The Data/the facts

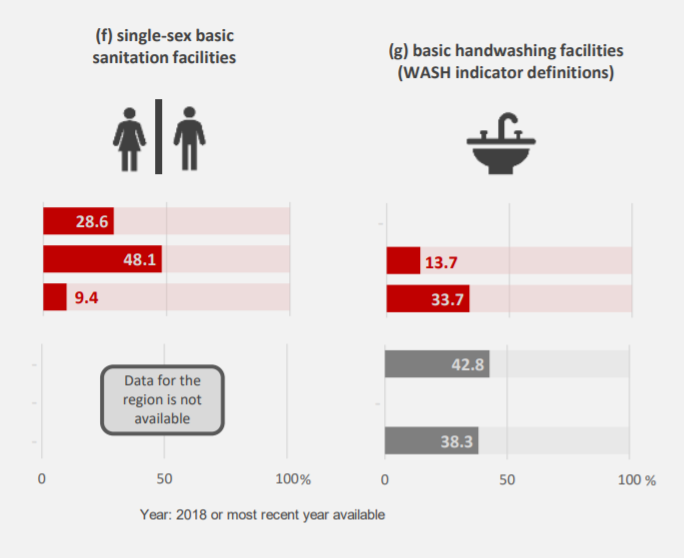

According to the GEM Education Progress Report, fewer than half of primary schools in sub-Saharan Africa have access to single-sex sanitation facilities. Starting in 1996, legislative reforms brought substantial improvements in Senegal’s water supply and sanitation sector (“Senegal,” 2020). However, despite basic water access service now reaching 81 percent of the Senegalese population, still only 9% of primary schools, 48% of lower secondary and 29% of upper secondary schools have single-sex sanitation facilities.

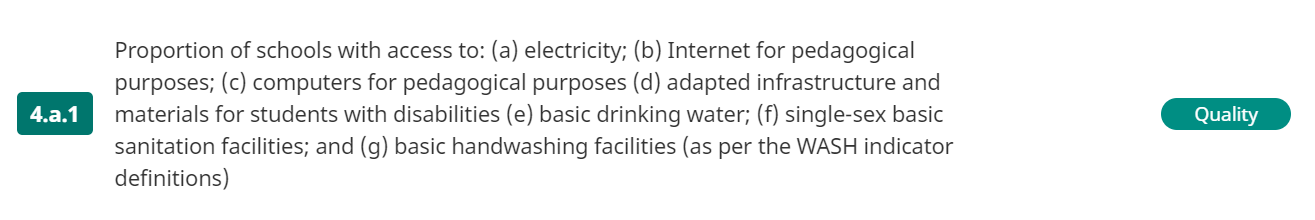

The UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 addresses the need to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Target 4.a and indicator 4.a.1 stresses the necessity to build and upgrade education facilities that are gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all. Indicator 4.a.1f more specifically addresses the need for single-sex basic sanitation facilities. (UN SDG, n.d)

Implications

Girls are particularly affected by limited access to single sex facilities in school because of the challenges they encounter when practicing menstrual hygiene, such as lack of privacy and safety, making them more vulnerable to dropping out from school (“GEM Report Education Progress,” n.d.).

In Senegalese society, menstruation is still a taboo subject with menstrual blood being considered “an impurity, a filth, an evil substance.” Due to this societal norm, menstruation must be handled with great discretion (“Statistics,”n.d.).

School aged menstruating girls, often labeled as impure or contaminated, suffer the most from limited or no access to private toilets. (“Menstrual Hygiene Management,” n.d.) Unlike their male classmates, they are often subjected to feelings of shame and embarrassment, discouraging them from attending school altogether. (“Changing Perceptions,” 2018).

A study of Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) in the Kedougou region, Senegal, undertaken by the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) and UN Women shows that “over 40% of the girls surveyed said that they missed school for at least one day per month” during their periods noting the absence of infrastructure as a reason for staying home. Indeed, the study revealed that none of the toilet facilities visited “had made provision for menstruating women to wash, clean themselves and change with privacy and dignity.” (“Menstrual Hygiene Management,” n.d.).

Young girls missing school due to a lack of appropriate infrastructure not only lowers self-esteem and perpetuates gender inequalities, but also translates into graver lifelong ramifications originating from dropping out of school leading to fewer opportunities that an education can offer (“Changing Perceptions,” 2018).

Actions taken today

As the WSSCC and UN Women study and statistics show, there is an urgent need to address the lack of single-sex sanitation facilities in Senegal. One important point to emphasize is that one cannot talk about single sex sanitation facilities without addressing the importance of menstrual hygiene management. However, despite its implications on young girls’ education and future, MHM is still a very low priority by many in the education and sanitation sector (“Changing Perceptions,” 2018).

Speak Up Africa is one organization based out of Dakar, Senegal that has introduced the importance of discussing menstrual hygiene management. One of their programs, the Africa Sanitation Policy and Advocacy Activator, supports sanitation initiatives that empower women (“Africa Sanitation,” 2018).

In 2013, WASH United, a German non-profit, started Menstrual Hygiene Day, a worldwide collaboration of 500 partners, from non profits, government agencies and the private sector, working together to bring awareness and advocacy about the importance of menstrual hygiene for all women and girls (“About Menstrual,” n.d.).

SIMAVI, PATH and WASH United and the social media campaign #menstruationmatters highlight how menstrual hygiene matters to achieve sustainable development goals, which do not specifically name and address MHM. An infographics they created in 2017 recommends several strategies to increase awareness and meet SDG4. One of them is to integrate education about MHM and puberty into school curricula. Another one is to build the capacity of teachers to teach about these issues with comfort (Menstruation matters, 2017). Women Deliver, another organization advocating for gender equality and the health and rights of girls and women around the world has made progress by bringing awareness to large international nonprofits during their 2016 conference. The International Committee of the Red Cross for example, facilitated a demonstration on how to make reusable sanitary pads (“2030 Agenda,” 2016.).

Moving forward

The Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) of WHO and UNICEF has proposed the following definition and standards for women and adolescent girls to be able to manage menstruation hygienically and with dignity (“MHM,” n.d.) :

Based on this definition the addition of a few strategies would improve the SDG indicator 4a.1 to address menstrual hygiene management needs. I suggested adding:

- h) menstrual hygiene materials to absorb or collect menstrual blood,

- i) water and soap within a place that provides an adequate level of privacy for changing materials or washing stains from clothes and drying reusable menstrual materials

- j) disposal facilities for used menstrual materials (from collection point to final disposal)

- k) accurate and pragmatic information (for females and males) about menstruation and menstrual hygiene (“MHM,” n.d.).

Adding these points to SDG4 would truly be a catalyst for change, making MHM an official issue to solve to allow women to thrive in today’s world.

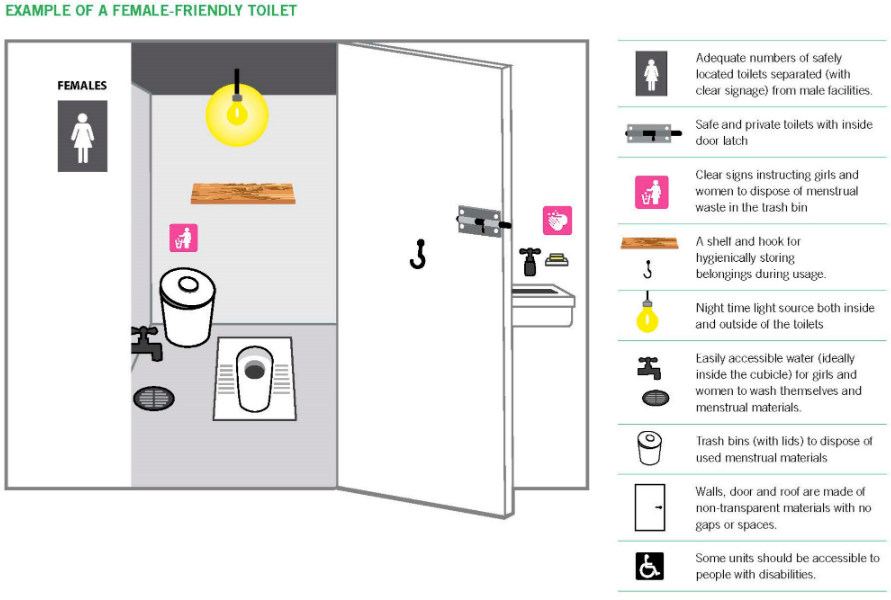

In their paper, “Making the Case for a Female-Friendly Toilet”, Schmitt et al. also propose an amazing a female-friendly toilet design which I hope will start conversations among designers and policy makers bringing comfort and safety to millions of girls and women (Schmitt et al., 2018, p.5).

References

The 2030 Agenda: What role does menstrual hygiene play? (2016). Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/menstruation-hygiene-day-girls/

About Menstrual Hygiene Day. (n.d.). MHDay | Global. https://menstrualhygieneday.org/about/about-mhday/

Africa Sanitation Policy and Advocacy Activator ⋆ Speak Up Africa. (2018, December 20). Speak Up Africa. https://www.speakupafrica.org/program/africa-sanitation-policy-and-advocacy-activator/?color=blue

Changing Perceptions Around Menstrual Hygiene Management and Why It’s Important ⋆ Speak Up Africa. (2018, November 13). Speak Up Africa. https://www.speakupafrica.org/changing-perceptions-around-menstrual-hygiene-management-and-why-its-important/

GEM Report Education Progress. (n.d.). GEM Report Education Progress. https://www.education-progress.org/en/articles/quality/

Integrated School Health Program for Child Survival. (n.d.). Amref Health Africa in the USA. https://www.amrefusa.org/where-we-work/senegal/integrated-school-health-program-for-child-survival/

MHM: Menstrual Hygiene Management. (n.d.). MHDay | Global. https://menstrualhygieneday.org/about/why-menstruationmatters/

Menstrual Hygiene Management: Behaviour and Practices in The Kedougou Region, Senegal. (n.d.). WSSCC UN WOMEN. https://www.wsscc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Briefing-Note-%E2%80%93-Menstrual-Hygiene-Management-Behaviour-and-Practices-in-the-Kedougou-Region-Senegal-WSSCC-UN-Women.pdf

Schmitt, M., Clatworthy, D., Ogello, T., & Sommer, M. (2018). Making the Case for a Female-Friendly Toilet. Water, 10(9), 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10091193

Senegal. (2020, February 28). Globalwaters.org. https://www.globalwaters.org/WhereWeWork/Africa/Senegal

Statistics on Menstrual Hygiene in Senegal, Niger and Cameroon Are Now Available; Product of Action-research in the Joint WSSCC-UN Women Program. (n.d.). UN Women | Africa. https://africa.unwomen.org/en/news-and-events/stories/2018/02/des-statistiques-sur-lhygiene-menstruelle-au-senegal-au-niger-et-au-cameroun-disponibles

WASH United Simavi (2017). Menstruation matters to everyone, everywhere. https://menstrualhygieneday.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/MHDay_MHM-SDGs_2017_RGB_fin.pdf

Who Stands for the Planet?

By Hinda Majri and Maria Mongelluzzo

Climate change is a topic dominating many conversations in recent years. From regular reports of the increased occurrence and intensity of natural disasters, like wildfires in Australia, to young activists like Greta Thunberg voicing their concerns on a global stage, to the continued fight for environmental protections and policies, such as the Green New Deal, climate change seems to be on everyone’s mind.

But who is responsible for teaching K12 students about climate change in the United States and ensure future generations have a more sustainable relationship with the Earth? What impact does climate change curriculum have outside the classroom?

Background

The UN Sustainable Development Goal 13[1] specifically addresses climate change. Target 13.3[2] and Indicator 13.3.1[3] stress the need to incorporate climate change curricula at every level of education (UN Sustainable Development Goals, n.d.). Current UNESCO data suggests their focus is on the targets and indicators related to resilience and adaptation to natural disasters and hazards (United Nations, n.d.). This seems appropriate given the dire circumstances surrounding natural disasters but leaves individual countries, states, and even schools to make decisions about how, and if at all, they will address climate change education.

While UNESCO data is not currently available, other institutions have attempted to gauge attitudes about climate change education in schools in the United States. An NPR/Ipsos survey considered teacher opinions of climate change education in the classroom[4] (Kamenetz, 2019).

Using this and other information, the U.S. can begin to understand public opinions and how to incorporate climate change education into classrooms.

Who Takes a Stand Around the World?

It is important to consider the progress made by other countries in incorporating climate change education into the classroom.

In late 2019, Italy became the first and only country to create a policy that requires public elementary schools to incorporate climate change education into courses including geography, math and physics (Nace, 2019).

In January of this year, New Zealand created a national climate change curriculum for middle school students. While not compulsory, teachers will have access to classroom materials and teacher resources to help students learn about climate action and managing climate anxiety (Ramirez, 2020).

Who Takes a Stand in the U.S.?

In most U.S. states, it is up to individual schools or school districts to decide how to incorporate climate change education into their curricula, a challenging task considering the little resources and lack of funding most schools are facing.

Thankfully, many organizations and initiatives provide support to schools, local districts and communities. NASA dedicates a section of their website to professional development courses, workshops and resources for schools. The STEM412 Global Climate Change Education for Middle School course, for example, is a collaborative effort with PBS Teacherline that offers education professionals training on how to engage middle-school students and help them understand the causes and effects of climate change (PBS, n.d.).

In 2019, Washington state invested $4 million to train teachers on how to incorporate climate education into their lessons and classrooms (Pailthorp, 2019). Focusing on local, visible problems, hundreds of teachers have participated in various training across the state including going on-site locations where climate change problems, such as wildfires and sea-level rise, can be seen and better understood (Pailthorp, 2019). For example, during a training focused on solid waste and garbage, teachers visited and learned from Seattle Public Utilities (Pailthorp, 2019).

The Zinn Education Project offers workshops for schools and teachers unions as well as classroom-tested lessons for elementary through high school through their Teach Climate Justice Campaign. Their People’s Curriculum for the Earth is a collection of articles, role plays, simulations, stories, poems, and graphics to help animate teaching about the environmental crisis.

One of the simplest and most successful actions the Zinn Education Project promotes is to take the pledge to teach climate justice. Sarah Giddings, Middle School Social Studies teacher in Mesa, Arizona took the pledge and says that lessons on climate change took her students “from a place of what appeared to be indifference and complacency, to a place of inquiry, compassion, and activism” (Zinn, 2020).

Teachers also get students involved in activities like The Climate Change Challenge where students come up with creative solutions to reduce harmful effects of climate change. Stephanie Kadison, a High Science Teacher from Alabama, shared that “one student came up with [a] light switch that turned off if there were no sound waves for more than 30 minutes to save energy” (Bigelow & Swinehart, 2020).

Beyond the classroom, the Zinn Education Project encourages youth engagement by offering a list of opportunities to engage in climate justice actions like the Nature Bridge Summer Programs or Climate Generation.

Finally, the project also encourages grassroot organizing by featuring successful resolutions to adopt a climate curriculum like the one passed in Portland School district from the continued pressure from students, parents and teachers.

The Impact

Students are having an impact outside of the classroom. From what they learn in school, students are influencing their parents, changing and opening their parents’ minds about climate change: “The North Carolina study, published in May 2019 in research journal Nature Climate Change, found that middle school-aged students who learned about climate change were pretty good at getting their parents to think differently about the issue.” (Sayler, 2019)

Climate change education also has a real impact on communities: “In 2016, Nature Energy released a study that showed that Girl Scouts who learned about energy-saving techniques were able to bring them into their homes. Kids have also proven effective at getting their parents to recycle more, according to a study in Waste Management” (Sayler, 2019).

As our climate continues to change, climate change education offers some hope. Hope that decision makers will make this a priority for future generations.

We leave you with this final thought:

Footnotes

[1] Goal 13: take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

[2] Target 13.3: improve education, awareness-raising and human institutional capacity on

climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning

[3] Indicator 13.3.1: number of countries that have integrated mitigation, adaptation, impact

reduction and early earning into primary, secondary and tertiary curricula

[4] The NPR/Ipsos survey resulted from polling approximately 1,000 adults and 500 teachers

References

Bigelow, B. & Swinehart, T. (2020). A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis. Retrieved from https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/peoples-curriculum-for-the-earth

Kamenetz, Anya. (2019, April 22). Most teachers don’t teach climate change; 4 in 5 parents wish they did. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2019/04/22/714262267/most-teachers-dont-teach- climate-change-4-in-5-parents-wish-they-did

Nace, Trevor. (2019, November 19). Italian law to require climate change education in grade school. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/trevornace/2019/11/19/italy-law-to-require- climate-change-education-in-grade-school/#12c82e765dae

NASA. (2020, February 12). Professional development courses, workshops and resources. https://climate.nasa.gov/resources/education/edOpps/

Pailthorp, Bellamy. (2019, March 4). Washington invests $4 million this year to bring climate science into classrooms. Retrieved from https://www.knkx.org/post/washington-invests-4- million-year-bring-climate-science-classrooms

PBS NASA. (n.d.). Resources for Teaching Global Climate Change in Middle School. http://www.pbs.org/teacherline/catalog/courses/STEM412/?utm_source=em&utm_medium=new s&utm_campaign=courses_sum10

Ramirez, R. (2020, January 14). New Zeal(and) for climate education. Retrieved from https://grist.org/beacon/new-zealand-for-climate-education/

Sayler, Z. (2019, May 23).

UN Sustainable Development Goals. (n.d.). Knowledge Platform. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg13

United Nations. (n.d.) The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019. Retrieved from https://undesa.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=48248a6f94604ab98f6ad29fa 182efbd

Zinn Education Project. (2020). https://www.zinnedproject.org/campaigns/teach-climate-justice