South Africa has had a difficult past. Social, racial and institutional issues have lead to tragic inequality between white, black, Indian, and non-white South Africans. These problems have permeated South Africa’s education system, leading to significant equity issues in education access. To understand the evolution of the education system in South Africa, we must first understand the historical events that continue to influence South Africa today.

Colonization

Colonization of South Africa began in 1653 with the establishment of Cape Town (then known as the Cape of Good Hope) as a rest stop for the Dutch East India Company, which transported slaves to European colonies. After the discovery of diamonds in South Africa, the British and Dutch fought over the territory until the British won and South Africa became a British territory in 1806. (This conflict is known as the Anglo-Boer War.) By this time, the rest stop had grown into a colony in which the British, Dutch (Afrikaners), and indigenous groups lived together uneasily. In 1931, South Africa was granted independence from the United Kingdom and the Afrikaners and white English-speaking citizens sought to reconcile politically and ethnically charged conflict. By 1948, the two sides had politically joined to create and elect the National Party. The National Party went on to establish one of the most tragic (and well-known) institutionalizations of racism in human history.

Apartheid

“Apartheid” is a Dutch word meaning “separateness” or “a state of being apart.” In 1948, the ruling National Party institutionalized racism based on race categorizations, including “White,” “Black,” “Non-white,” and “Indian.” Apartheid was only dismantled in 1994, and South Africa continues to struggle with the mess it left behind.

Rationalization for something as atrocious as the existence of South Africa’s apartheid in our day and age can be hard to understand, but lets think back on the effects of colonization on Afrikaners in South Africa after South Africa was granted independence from the United Kingdom. By the time independence came, Dutch Afrikaners had long since been forced to sever ties with Holland as a result of the Anglo-Boer War in 1806. After gaining independence from the U.K. in 1931, Afrikaners no longer had formal ties with Europe. By 1948, Afrikaners (a very small group compared to the black, Indian, non-white South Africans, and British South Africans) had their own language and identity and were fearful of being engulfed by the other two growing populations. Some sort of separation was thought to be the only way to preserve Afrikaner language and identity. Apartheid was the Afrikaners solution to their perceived problem.

Life Under Apartheid

The quality of everyday life under apartheid depended on your skin color. Policy under apartheid physically separated black and white South Africans by assigning black South Africans to live in encampments called “bantustans” which were overcrowded and bereft of basic necessities like clean water and electricity. The process of establishing apartheid often required physically removing black South Africans from their homes and forcefully relocating them to their assigned bantustan. While white South Africans enjoyed the human rights guaranteed to white citizens, black South Africans were severely limited outside their bantustan in the jobs they could hold, where they could go, and activities they could participate in. Black South Africans could not travel within the country without passes and in many cases, black South Africans were stripped of their citizenship. Without the ability to obtain a South African passport, these people could not even leave their bantustan.

Bantu Education

Apartheid had a huge impact on the education system in South Africa. Before the establishment of Apartheid, schooling was largely private and run by various religious and secular establishments that, while accepting some government money, created their own curriculum and essentially governed themselves. The Bantu Education Act of 1953 gave the National Party the power to take over administration of any South African school, effectively allowing the government to segregate the education system and funnel almost all educational resources toward white schools. The philosophy masking this blatant racism might best be summed up by Anand Singh’s quotation of D.J. du Toit (an Afrikanner education writer):

“We are the Black man’s guardians. It is our duty to bring him up – om hom op te voed…This duty must we do…Not by letting him run wild on our village outspans and on the streets of our urban areas…but by bringing him up according to the principles and tenets of his own culture; by treating him as a growing, developing fellow being all the time, using education only as a means of training him to citizenship of his own tribal state, on the sure and only foundation of his own cultural tradition.”

As a result, teacher training in black schools severely suffered, and teachers used whatever resources that were given to them by the government. This gave the government a tremendous amount of control over the education of black South Africans, and this control was used to instill values in black students that oriented then toward a life of servility. These values (punctuality, neatness, a sense of duty, reliability, mannerliness, persistence), embedded in curriculum by the Ministry of Education were meant to systematically condition black students to accept apartheid and racial inequality as normal and natural.

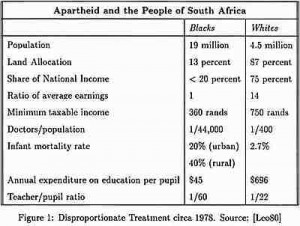

Most black South Africans were not educated past secondary school and many had no education at all. Bantu Education was funded solely through the taxes levied on bantustans. In 1953, the South African government spent on white students over eight times the amount of money it spent on black students. By 1978, over fifteen times the money spent on black students was spent on white students.

Bantu Education would not be repealed until apartheid itself was dismantled in 1994. Check back in March to see more discussion on the recent changes in education made under South Africa’s young democratic government.

Looking for more information? Try reading these articles!

Low, Victor N. “Education for the Bantu: A South African Dilemma.” Comparative Education Review 2.2 (1958): 21-27. Web.

Ntombele, Sithabile. “The Progress of Inclusive Education in South Africa: Teachers’ Experiences in a Select District, KwaZulu-Natal.” Improving Schools 14.1 (2011): 5-14. Web.

Rose, Brian W. “Bantu Education as a Facet of South African Policy.” Comparative Education Review 9.2 (1965): 208-212. Web.

Singh, Anand. “Towards a Theory of National Consciousness: Values and Beliefs in Education as a Contribution to ‘Cultural Capital’ in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 40.5 (2005) 323-343. Web.

Ndimande, Bekisizwe. “From Bantu Education to the Fight for Socially Just Education.” Equity and Excellence in Education 46.1 (2013) 20-35. Web.