The problems with policing in America have, for centuries, been a long-unheard outcry from communities of color, dating back to the origins of police practices as slave-catching patrols[1]. In the summer of 2014, four Latino citizens killed by police in the Monterey County seat Salinas, CA brought the issue closer to MIIS than ever before. Although the officers involved were eventually cleared of all charges by the DA, the public unrest that was sparked following the shootings had already brought the topic of much-needed police reform to the city[2]. The Salinas Police Department’s (SPD) first act was the request of a review by the Community Oriented Policing Services department of the Department of Justice. Their 2016 report highlighted, among many concerning discoveries, a weak relationship between the SPD police and the communities they were meant to serve and protect[3].

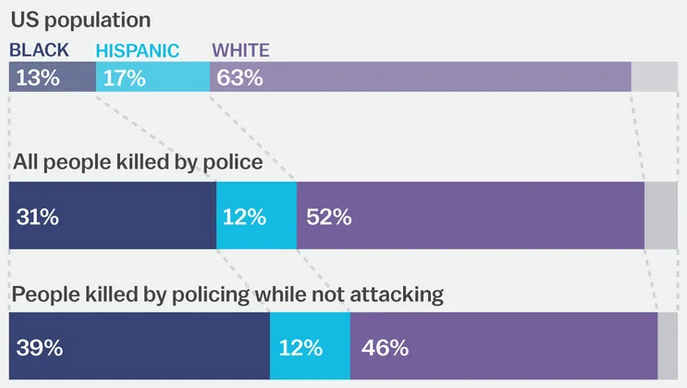

Police reform over the years can be characterized by two steps forward, one step back, sometimes achieving progressive victories such as Miranda v. Arizona (1966) (which instituted the required reciting of Miranda rights by law enforcement upon arrest)[4], and just as quickly reverting back with Terry v. Ohio (1988) (which led to the famously racist policy of Stop and Frisk)[5]. Although discussed, debated, and legislated upon for years, awareness of racism present in policing practices was not brought into mainstream American consciousness until the early 1990’s, when the 1992 Los Angeles riots made the issue unavoidable. Conscious or not, racism in policing didn’t become a topic of priority for mainstream American politics until the 2010s, thanks in large part to the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement following the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer[6]. They brought to attention the drastic disparity between the rate black Americans, often men, and white Americans are killed by police[7].

The recommendations made by the DOJ in their report brought about a host of new initiatives at the SPD to strengthen internal policies and practices, as well as several new programs for the much needed strengthening of community relations[8]. One such program was Why’d You Stop Me? (WYSM), which our very own META Lab was contracted to help assess (as required by the grant which funded WYSM in Salinas). The final report, published in 2018, is a prime example of what happens when qualified, well-intentioned data researchers are given unrealistic requirements to evaluate programmatic success or failure. The META Lab members who created this report would likely agree, as they state in the methodology section it was “… expected that the time allowed under the grant would be insufficient for substantial changes in perceptions to be formed, much less detected”[8] (p. 16). The researchers specified four long-term goals to evaluate which would have served as excellent indicators for program success[8] (p. 12-13), had their timeline allowed for a full assessment of them.

Authors of the report are very clear in the limitations of their findings, none of which result from any shortcomings of the researchers themselves. They can instead be traced to the inadequate timeline that the researchers were offered to produce a robust evaluation of the program. The final recommendation in the report, and perhaps the most important one, is “to continue to monitor and test whether or how the program is having an effect” and “that a follow-up evaluation be funded and conducted in Salinas to test whether general outreach has been achieving the goals that were behind the grant application that initiated this project and this process in Salinas”[8] (p. 49). Were Salinas decision makers not to heed this final recommendation, they would face great risks when basing future decisions on highly limited data.

Quantitative evaluation is a vital component of any program, but when done inadequately can cause more harm than good. Decision makers must understand that holistic assessment cannot be an afterthought to new programs and policies, but rather an integral part of any earnest initiative for positive social impact. Even if a program fails to meet its intended goals, a well-designed assessment plan applied from start to finish can inform future progress. Failure is a far better teacher than success, and without assessment we are rendered unable to even determine the difference. Unfortunately, the price of failure when it comes to police reform is the loss of lives, disproportionately black and brown, and continued failure (or lack to assess thereof) can not be tolerated.

References

[1] https://lawenforcementmuseum.org/2019/07/10/slave-patrols-an-early-form-of-american-policing/

[2] https://www.cnn.com/2014/05/22/us/california-protest-police-shooting-hispanics/index.html

[3] https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/montereycountyweekly.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/9/db/9db445fc-f075-11e5-9c0f-cff328653ea9/56f1ba4792594.pdf.pdf

[4] https://www.oyez.org/cases/1965/759

[5] https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/stop_and_frisk

[6] https://blacklivesmatter.com/herstory/

[7] https://www.vox.com/identities/2016/8/13/17938186/police-shootings-killings-racism-racial-disparities

[8] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Gk6mZUK-vAfS8sE_Ql58fMJakcquf3fW/view?usp=sharing

You must be logged in to post a comment.