By Magdalena Castillo

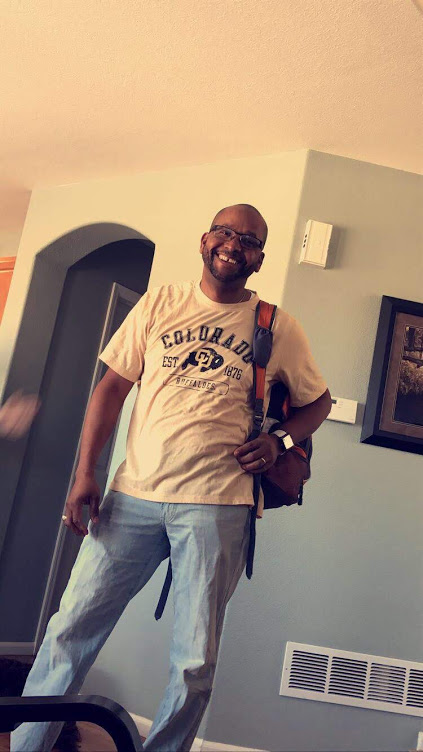

This is my father. His name is Miguel Castillo and he is a Dominican immigrant who came to this country at the age of 26, for me. He left his language, culture, career, family, friends, and undeniably delicious cuisine only to be welcomed into this country with consistent pull-overs by the police in Denver, Colorado; an event that took place so often that he thought it was just a normal part of the new American culture he had to adapt to.

In a sense, that was true, and still is. Police pull over and shoot minorities–but especially black men and boys– as a result of structural racism in this country. It is so ingrained in our culture, that instead of fixing the institutions created to oppress the underrepresented, it’s easier to just learn how to cope. Smile at the cops. Never leave your house before assessing your car (especially your headlights). Make sure you always say “yes sir” and comply. There has been an issue with the system, and while I have always understood that there are good cops as a concept, I have never seen them.

I came into the presentation curious and with an open mind, which I’m thankful for because I came out of it a more evolved person. I agreed with a major part of the presentation that the largest part of violence by firearms is because of American culture. “How much is the cops fault?” was a quote that still stuck with me 24 hours after the discussion and still does. It made me realize that, yes, cops need to be held accountable for unlawful shootings and there potentially needs to be better training for those joining the police force, especially in susceptible-to-crime neighborhoods. But in order to fix that we need to fix the issue of racism, the lack of access to resources that allow young children to join groups and tools that allow them to have a space of belonging that aren’t dangerous (in the case of gangs), and education (among many other factors). Chief Kelly showed compassion not only for the young people whose lives were affected by arrest or shootings as a result of gang-related activity, but for the problems that got them to be in that position in the first place. It showed me the humanity in cops that I didn’t initially focus on prior to this talk. I felt shivers down my arm when he told a story about him demanding that his officers take off their masks and gear when a child was witnessing his family member being arrested. I felt a smile crawl onto my face when he told us that he implemented a program that put place-based officers in neighborhoods that needed extra attention. The sole idea that cops gathered with a community of minorities and got to know them and understand them to me represents an important step towards peacebuilding, which is to rebuild broken trust by coming together and understanding each other’s culture, history, and dynamics. I commend Chief Kelly for supporting and starting that program, and it’s unfortunate that due to funding, it had to be expelled. This was another great reminder for me–before I critique I must first learn the whole story–it’s not as easy as just putting in beneficial programs like that. The program needs to be funded, and when there is no money dedicated to these services, it makes peacebuilding in local communities that much harder.

I was honored to have been in that room and to have been part of such a thought-provoking conversation. While I still have questions and concerns with some of the arguments made, I left with more knowledge, more empathy, and a feeling that I had a lot more thinking to do. Bad cops exist. There is a larger problem with the justice system and the police force. But there are great cops out there. Ones that care about their communities and do what they can to take responsibility for issues they see in the towns they are in charge of. If my dad reads this, I want him to know that some cops are on his side, and if there are more cops like the one I met, then there is hope for a better future with less fear.

I see you now, good cops.

I see you.