Home » Access

Category Archives: Access

International Education for Sustainable Development: Tackling the UN SDGs through Education Abroad

Credit: Svetlana Kijevčanin

In the United States, increasing numbers of inbound and outbound students have gained interest in global issues like climate change and higher education’s response to it. For the U.S. international education sector, this response has manifested in the inclusion of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) in international education programs. The UN SDGs are “an urgent call for action by all countries – developed and developing – in a global partnership” to tackle the wicked problems impacting societies across the globe, which, in addition to climate change, also include issues like hunger, poverty, and social inequality.

Interest in the UN SDGs has grown in recent years for students, higher education institutions, and international education organizations. In response, the Forum for Education Abroad (FEA), for example, now provides guidance to and resources for international education practitioners in using education abroad to advance the UN SDGs. Additionally, Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) has aligned their study abroad programs with the UN SDGs. Using available program information to match each study abroad program to one or more SDGs, IUPUI allows students to select which programs to participate in based on which UN SDGs they’re interested in.

FEA provides two definitions for international education, one for the field, and another for participants. FEA defines the international education field as “a field involved in facilitating and supporting the migration of students and scholars across geopolitical borders. Professionals…may be employees of educational institutions, government agencies, or independent program and service providers.” For participants, international education is defined as “the knowledge and skills resulting from conducting a portion of one’s education in another country. As a more general term, this definition applies to international activity that occurs at any level of education (K-12, undergraduate, graduate, or postgraduate)”. As such, not only can education abroad support sustainable development in the U.S., it can also be used to support sustainable development abroad. While education abroad programming can support sustainable development by targeting multiple UN SDGs, all programs, whether through their structure or through participants who leverage their education abroad experiences in their future work, achieve this through UN SDG 17 – Partnerships for the Goals. More specifically, education abroad programs achieve sustainable development through UN SDG 17.17, which seeks to “encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships”.

Education abroad, where participants cross national borders to engage in a learning experience through a program offered by a higher education institution, governmental, or provider organization, is just one facet of international education. Evidence suggests that there is a positive relationship between the inclusion of the UN SDGs and education abroad program outcomes. For example, a recent study published by Zhang and Gibson (2021) investigating the long-term impact of study abroad on attitudes and behaviors regarding sustainability uncovered that participants had still maintained a mindset that prioritized sustainability, engaged in behaviors promoting low-waste and responsible consumption, and that the program had impacted their career trajectories towards work with a focus on sustainability. This aligns with UN SDG Goal 12 on responsible consumption and production, although on an individual level. Despite the benefits of education abroad for promoting individual-level sustainable practices and mindsets, participants must also grapple with the environmental costs associated with education abroad, an idea explored by recent research from Campbell, Nguyen, and Stewart (2022). Other education abroad programs that can be used to target other SDGs, such as SDG 15 (life on land) and SDG 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions) include the University of Wyoming’s Silk Road and Beyond: Historical and Environmental Treasures program in Uzbekistan and Middlebury Institute of International Studies’ experiential learning programs like Peace and Reconciliation in the Balkans and Exploring Sustainable Agriculture Transitions in Rural Colombia.

Education abroad can also support progress towards the UN SDGs through programs designed for participants to come to the United States. Evidence suggests that investing in community leaders through education abroad and international education scholarship programs can lead to improvements in leadership effectiveness and other knowledge, skills, and attributes (KSAs) that can benefit both the public and private sectors as well as local communities. One education abroad program focusing on this is the International Research and Exchanges Board’s (IREX) Community Solutions Program (CSP). Since 2010, CSP has supported 739 fellows from 83 countries that have impacted more than 600,000 people through follow-on community development initiatives as a result of program partnerships with 419 host organizations in 40 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The U.S. practicum and follow-on initiatives that program alumni engage in can – and have – targeted a number of UN SDGs, like UN SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and SDG 3 (good health and well-being). For example, CSP 22’ recipient Bogatoz Kozhakhmetova plans to support rural women’s economic empowerment through social entrepreneurship in Kazakhstan. CSP 18’ recipient Daren Paul Katigbak supported education and outreach initiatives related to HIV and sexual health in the U.S., and continued this work in the Philippines. Other programs that could be aligned with the UN SDGs include the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) and the Fulbright Program.

The UN SDGs present an opportunity for the U.S. international education sector to consider including the SDGs in education abroad programming not only for recruitment purposes but also in solidifying education abroad as a vehicle for supporting local, national, and international efforts to address issues impacting governments, societies, and individuals. However, the inclusion of the UN SDGs does not have to stop at education abroad programming. The UN SDGs, as Cordell states, also present an opportunity to “revisit strategic investments…in scholarships and exchanges…[and] training and workforce programs, national-level university systems, and youth empowerment programs”. Thus, the applicability of the UN SDGs can extend beyond U.S. education abroad programs to include various other programs benefiting individuals at both the domestic and international levels.

References

Botagoz Kozhakhmetova | IREX. (n.d.). Www.irex.org; IREX. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.irex.org/people/botagoz-kozhakhmetova

Campbell, A. C., Nguyen, T., & Stewart, M. (2022). Promoting International Student Mobility for Sustainability? Navigating Conflicting Realities and Emotions of International Educators. Journal of Studies in International Education, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153221121386

Community Solutions | IREX. (n.d.). Www.irex.org; IREX. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.irex.org/project/community-solutions

Cordell, K. (2021, September 24). The Sustainable Development Goals: A Playbook for Reengagement. Www.csis.org; Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/sustainable-development-goals-playbook-reengagement

Daren Paul Katigbak | IREX. (n.d.). Www.irex.org; IREX. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.irex.org/people/daren-paul-katigbak

Forum for Education Abroad. (2021). Advancing the UN Sustainable Development Goals through Education Abroad. https://doi.org/10.36366/g.978-1-952376-09-2

Hellman, K. (2022, October 6). International Education: A Catalyst for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Network.nafsa.org; NAFSA. https://network.nafsa.org/blogs/dale-lafleur1/2022/10/06/international-education-a-catalyst-for-the-unsdgs

Kendall, N., Kaunda, Z. & Friedson-Rideneur, S. (2015). Community participation in international development education quality improvement efforts: current paradoxes and opportunities. Educ Asse Eval Acc 27, 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-015-9210-0

Marschner, D. (2022, May 14). When it comes to studying abroad, SDGs matter to students. University World News: The Global Window on Higher Education; University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20220510135024393

Martel, M. (2019). Leveraging Higher Education to Promote Social Justice: Evidence from the IFP Alumni Tracking Study. Ford Foundation International Fellowships Program Alumni Tracking Study, Report No. 5 New York, NY: Institute of International Education

Musa, E. (2012). Impact of ford foundation international fellowships program (IFP) on leadership effectiveness in kenya [Thesis]. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/96697

O’Malley, B. (2023, February 11). Survey shows universities accelerating action for SDGs. University World News; University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20230211062743570

Study abroad and the sdgs: apply to a program: study abroad: indiana university-purdue university indianapolis. (n.d.). Abroad.iupui.edu; Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://abroad.iupui.edu/apply-program/sa-sdgs/index.html

United Nations. (2015). The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

Winter, Spring, and Summer Experiential Learning Courses | Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. (n.d.). Www.middlebury.edu. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.middlebury.edu/institute/academics/immersive-learning-study-abroad/semester-practica

WyoGlobal Alumni | Global Engagement Office | University of Wyoming. (n.d.). Www.uwyo.edu; University of Wyoming. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.uwyo.edu/global/get-involved/wyoglobal-alumni.html

Zhang, H., and Gibson, J. (2021). “Long-Term Impact of Study Abroad on Sustainability-Related Attitudes and Behaviors” Sustainability 13, No. 4: 1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041953

Taking Back What is Theirs: Women and Girls’ Access to Education in Afghanistan

Years after the US-led military intervention defeated the Taliban, around 2/3rds of Afghan girls still were out of school (Human Rights Watch, 2017a). Since regaining power in August 2022, the Taliban has banned girls from secondary and tertiary education again (Hadid, 2022). These events have intensified an already dire situation, leaving the future of Afghanistan’s women uncertain and jeopardizing the country’s developmental progress.

Prior to this, an Afghan government report (from 2015) indicated that the number of children attending school exceeded 8 million. However, Human Rights Watch disputed the accuracy of these figures in a report released a few years after (2017a). This is common among post-conflict governments due to displacement and unaccounted populations. This potential inaccuracy is noteworthy because it represents a negative trend in Afghan education as a positive one.

In addition to UN pressure, the Afghan government has legal obligations to supply education to its population. In the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Afghanistan ratified that it would ensure women equal rights, including in education (Human Rights Watch, 2017b). This obligation highlights the need for Afghanistan to prioritize and uphold its commitment to equal education. The failure to do so directly violates Afghan women’s rights and impedes the country’s progress toward development.

The Taliban: Brief History

The Taliban was formed in the 1990s by Islamic guerrilla fighters who promised stability after years of conflict (Maizland, 2021). Their beliefs stem from the harsh interpretations of the Pashtuns’ pre-Islamic tribal codes, which require women to be covered entirely, have a male chaperone, and be denied education. In 2001, a U.S.-led invasion ousted this government, and Afghanistan began to see improvement. But by 2021, US troops began withdrawing from Afghanistan, and the Taliban were able to regain control of the country – immediately reinstating these codes.

Education under the Taliban

Afghanistan was already struggling to close gaps in education between boys and girls after the Taliban in 2001. When leaders removed women and girls from schools, this set the country even further back. Additionally, to deter women and girls from attending schools, the Taliban began targeted attacks, such as acid assaults, sexual harassment, and kidnappings (Human Rights Watch, 2017b).

Simultaneously, existing problems inside and outside Afghan schools were intensified.

Inside schools (Human Rights Watch, 2017a):

- Lack of female teachers

- Overcrowding

- Gender segregation

- Poor infrastructure (60% of schools do not have toilets/drinking water)

Outside school (Human Rights Watch, 2017a):

- Gender-based violence

- Partner violence

- Higher costs of attendance

- Increased rate of child marriage

What does this mean for development?

Excluding half a population from education significantly reduces a country’s development. Already in Afghanistan, this has resulted in:

- Losses of up to 5% of Afghanistan’s GDP due to restricted opportunities for women (UNDP, Maizland, 2021).

- Increases in women arrested for “violating” discriminatory policies (Amnesty International, Maizland, 2021).

- Higher rates of child marriage (Maizland, 2021).

- 3.5 million children out of school – 85% being girls (Human Rights Watch, 2017b).

These statistics, plus increasing child/maternal mortality rates, will deprive communities of significant contributions and lead to societal unrest. How does Afghanistan expect to move forward when all of these factors work together to keep women and girls from education?

What is being done?

Women for Women International (WFWI) is combating this endemic. Through this organization, women can join others like them and learn to improve their health, understand their rights, and continue their education (Women for Women International, 2023). WFWI is creating an environment of learning that aims to enhance women’s well-being. Although WFWI is focused on reaching sustainable development goal 5, they recognize that women play a crucial role in realizing all SDGs.

WFWI’s Stronger Women, Stronger Nations program has reached over 125,000 women in Afghanistan. This program has significantly impacted populations of women. One woman, Nasima, attests that since she joined this program, she learned basic math, how to save money, and began sewing dresses. She uses her extra money to buy food and items for her family (Women for Women International, n.d.). Similarly, women who graduate from the program report understanding their rights better and having taken action to share the effects of violence against women in their communities (Women for Women International, 2023).

WFWI was forced to pause aid due to the Taliban’s control. However, since December they have been able to reopen their community centers/schools at reduced levels. Working alongside local communities and UN agencies, WFWI continues to advocate to end this education ban (Women for Women International, 2023).

Education empowers women and girls to understand their rights and take action against violence while enhancing development. International organizations, like WFWI, must continue to work with Afghanistan to ensure women’s rights are protected and access to education for all is facilitated.

Donate: Women for Women International

References

Amiri, W. (2023, March 7). Women, Protest and Power- Confronting the Taliban. Retrieved from Amnesty International website: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2023/03/women-protest-and-power-confronting-the-taliban/

Hadid, D. (2022, December 21). Taliban begins to enforce education ban, leaving Afghan women with tears and anger. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2022/12/21/1144703393/taliban-begins-to-enforce-education-ban-leaving-afghan-women-with-tears-and-ange

Human Rights Watch. (2017a, October 17). “I Won’t Be a Doctor, and One Day You’ll Be Sick” | Girls’ Access to Education in Afghanistan. Retrieved from Human Rights Watch website: https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/10/17/i-wont-be-doctor-and-one-day-youll-be-sick/girls-access-education-afghanistan

Human Rights Watch. (2017b, October 19). Afghanistan: Girls Struggle for an Education. Retrieved from Human Rights Watch website: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/10/17/afghanistan-girls-struggle-education

Maizland, L. (2021, September 15). The Taliban in Afghanistan. Retrieved from Council on Foreign Relations website: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/taliban-afghanistan

Women for Women International. (n.d.). My Name is Nasima: Life Changing Lessons. Www.womenforwomen.org. Retrieved from https://www.womenforwomen.org/stories/my-name-nasima

Women for Women International. (2023). What We Do. Retrieved from Womenforwomen.org website: https://www.womenforwomen.org/what-we-do

Yousafazai, S. (2023, March 8). On International Women’s Day, Afghan women blast the Taliban and say the world has “neglected us completely.” Retrieved from www.cbsnews.com website: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/international-womens-day-afghanistan-taliban-women-protest-say-world-neglected-us/

Making a Difference: Early Childhood Education in Refugee Camps

Since mid-2022, a minimum of 103 million people, of which 36.5 million are children, have been forcibly displaced because of conflict, violence, or persecution. 1 in 6 children have spent their early years surrounded by war and instability, and about 48% of all forcibly displaced children are not in school (Kirollos et al., 2018; United, n.d.-b). The majority of these people live in refugee camps and will stay in displacement for years, often without access to any education (Ensuring, 2021).

Understanding the need to provide access to education, some organizations have found their way into refugee camps. One of those organizations is PILAglobal. PILA is one of the few non-profit organizations focused specifically on providing early childhood education (ECE) to young children and families in refugee camps where there is zero access to education (PILAglobal, n.d.).

Why Early Childhood Education in Refugee Camps?

Many refugee children experience profound physical and emotional traumas from the conflicts they left behind and from daily life in refugee camps. They’re immensely vulnerable and are exposed to all risks ranging from sexual exploitation to forced recruitment and beyond (United Nations Children, 2017). Younger refugee children face additional challenges as the physical deprivation, psychological trauma, constant stress, and inadequate socioemotional and cognitive development can have lasting effects on their ability to learn, grow, and excel (Kirollos et al., 2018).

While education generally imparts important practical and cognitive skills, ECE specifically helps young children under the age of 6 learn how to handle the stressors they encounter and provides them safe areas to play, thrive, and create positive change by developing their tolerance, confidence, and hope (Grantham-McGregor et al., 2007). Additionally, ECE can provide language instruction in the majority language of the host country, which will provide refugee children a greater degree of school readiness. The provision of high quality ECE has also been shown to reduce gaps in outcomes between refugee children and native-born children, while also increasing academic performance, future employment opportunities, income, and overall health. Beyond the children themselves, ECE has also been shown to connect refugee families to the larger community, fostering social capital and social cohesions through the provision of spaces in which diversity, tolerance and respect are nurtured (Park et al., 2018).

Yet, despite this evidence, more than 200 million children under the age of 5 from around the world fail to reach their full developmental potential because they don’t have access to ECE (Grantham-McGregor et al., 2007).

PILAglobal

PILA recognized the growing need for ECE among refugees. So, in 2018, PILA opened its first Nest—an education and play space for young refugee children—in a community center in Lesvos, Greece. Since then, PILA has opened three additional Nest’s for refugees in Athens, Greece, and in Tijuana, Mexico (PILAglobal, n.d.).

In these refugee camps—which are often fraught with conflict and violence—PILA provides one of the only places where young children and their parents or guardians can feel safe, and learn. As its CEO states, “we are teaching for democracy…building social skills, problem solving, and confidence as a learner, to say nothing of math, science, and literacy” (L. Weissert, personal communication, February 24, 2023).

Understanding that families have different needs and wants, and that each country context is different, the Nest centers are inquiry- and play-based and look like the children they serve. There is no one size fits all model to ECE, rather, each program’s structure is unique, reflecting the needs of the communities, and being culturally responsive. PILA provides the infrastructure and materials, but then each Nest is maintained, in part, by the community it serves. And once it is established, local partners are brought in to provide additional funding and support, while ensuring the program is responsive to the needs of the community. PILA’s ECE program is thus highly sustainable and scalable (L. Weissert, personal communication, February 24, 2023).

Lindsay Weissert and her team have seen how providing ECE to young refugee children helps build social skills, confidence, and the disposition children need to solve the world’s problems. She believes that “these are children that will go on to solve the problems of their own countries and communities.”

Migration is not going to stop any time soon, and the need for quality education won’t end either. Data has shown that the number of child refugees has increased by a staggering 812% since the beginning of the 21st century (United, n.d.-b). Thus, governments, international organizations, and NGOs need to enact laws and increase their risk appetites to implement programs that will provide ECE to children, setting children up for learning and protecting them from the harms of refugee life. With improvements in access to quality education, we will be able to see a positive change in refugee life and the lives of refugee children.

References

Ensuring Quality Early Childhood Education for Refugee Children: A New Approach to Teacher Professional Development – World. (2021). ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/ensuring-quality-early-childhood-education-refugee-children-new-approach-teacher

Grantham-McGregor, S., Cheung, Y. B., Cueto, S., Glewwe, P., Richter, L., & Strupp, B. J. (2007). Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. The Lancet, 369(9555), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60032-4

Kirollos, M., Anning, C., Gunvor, K.F., Denselow, J. (2018). The War on Children. Save the Children International. https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/content/dam/global/reports/education-and-child-protection/war_on_children-web.pdf

PILAglobal | High Quality Education for Refugee Children. (n.d.). PILAglobal. https://www.pilaglobal.org/

Maki, P., Katsiaficas, C., & McHugh M. Responding to the ECEC Needs of Children of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Europe and North America. (2018). MPI. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/ECECforRefugeeChildren_FINALWEB.pdf

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2017). Unicef’s Programme Guidance for Early Childhood Development. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/media/107616/file/UNICEF-Programme-%20Guidance-for-Early-Childhood-Development-2017.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (n.d.-b). Refugee Statistics. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

Free Access to Education for All Through Literacy

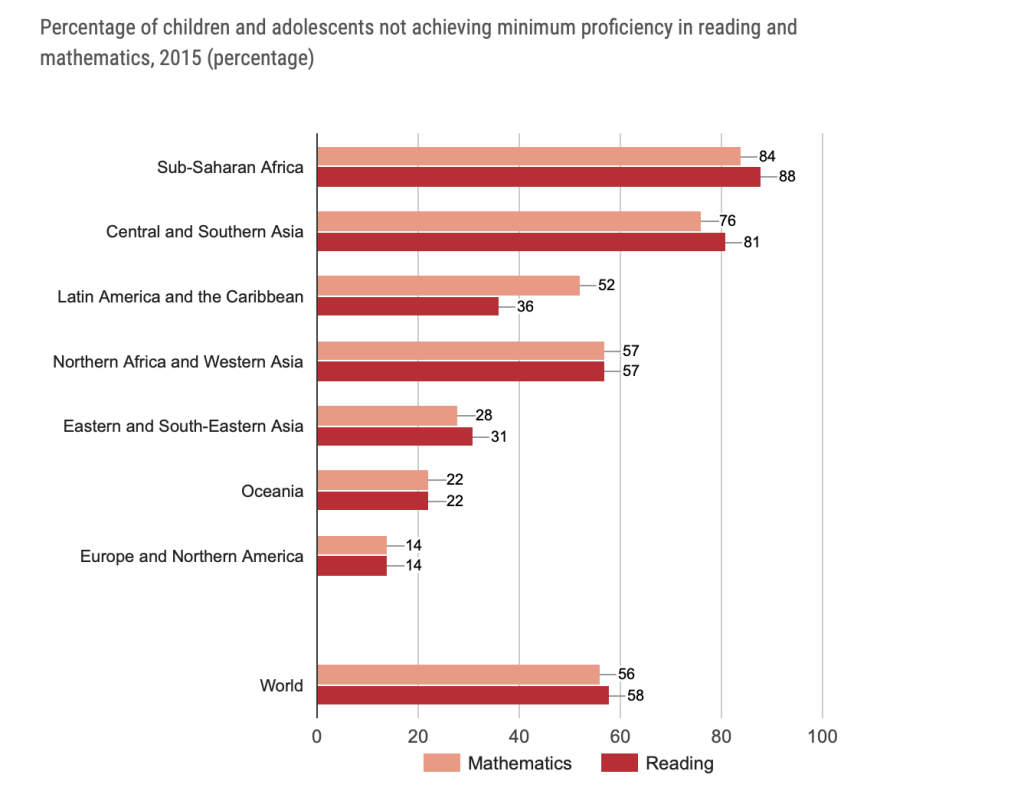

Literacy is a huge problem throughout the world, especially in developing countries such as Latin America. According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, about “9% of individuals ages 15 and older are illiterate which equates to about 38 million” (cepal.org) illiterate individuals in Latin America and the Caribbean. A majority of these individuals are women who make up about 20 million of the 38 million in Latin America and the Caribbean. Literacy is such an important part of education to end the cycle of poverty as well as contribute to an increase in the country’s economy by having more job opportunities for individuals to seek higher paying jobs. According to the United Nations Social Development Goals, Goal 4: Quality Education is set to “ensure inclusive equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (SDG Indicators). Below are the percentages of children and adolescents who are not achieving minimum proficiency in math or reading in 2015:

According to the World Literacy Foundation, the impact of illiteracy in a country can cost a country’s global economy an estimated 1.9 trillion dollars annually, as well as increase the amount of unemployment in a country if individuals do not have proper literacy skills that employers need which can cause vacancies in these industries. One social impact of illiteracy is that it can negatively affect the importance of education which can continue the cycle of poverty through generations.

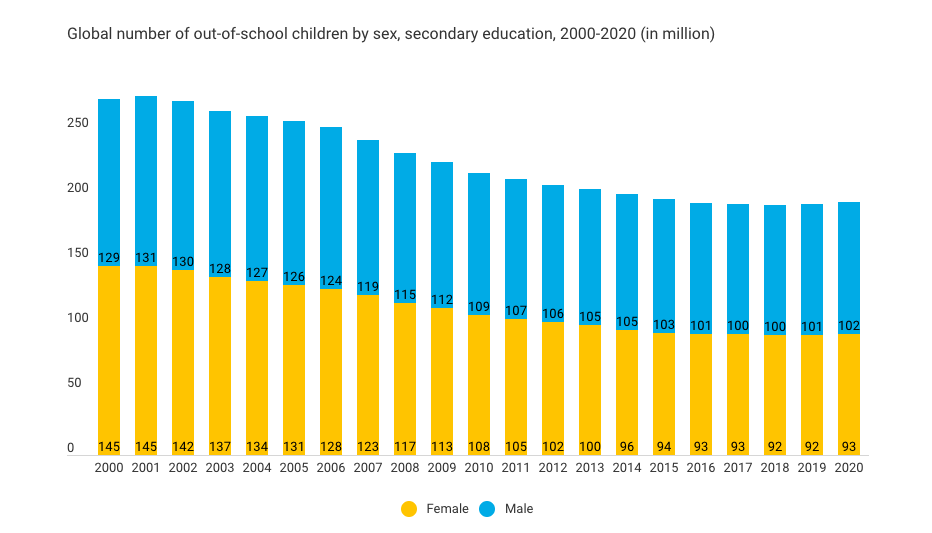

The second social impact of illiteracy is poor health outcomes, welfare dependency, gender inequality, and lack of social skills for women and men. There are currently 5.5 million more girls than boys that are out of school worldwide and that number will most likely increase. The health impact of illiteracy can impact a child’s health and survival due to the mother’s lack of understanding of health education and behaviors. Illiteracy can impact an individual’s ability to understand health information, read medication labels, and make accurate decisions on the health of themselves and their families.

The World Literacy Foundation is “a global nonprofit organization striving to ensure that every child regardless of geographic location has the opportunity to acquire literacy skills and books to reach their full potential to succeed in school and beyond” (World Literacy Foundation.org). The World Literacy Foundation was established in 2003 in Melbourne, Australia to bring books, tutoring, and literacy resources to children without any support” (The World Literacy Foundation.org). They expanded to other countries around the world to combat illiteracy.

The World Literacy Foundation’s impact on the Aprende Leyendo program in Manizales, Columbia, and the impact in 2022 globally has been outstanding. In 2020 through the Aprende Leyendo program, “940+ children and parents accessed services through the World Literacy Foundation, 1,170+ free books, and literacy packs were distributed, 60+ reading sessions were facilitated, 450 volunteers hours were donated to the foundation’s projects as well as 150+ eBooks and digital activities were created for the Dingo App which allows access to digital books in English and Spanish for students with poor internet connection in rural communities” (Aprende Leyendo, World Literacy Foundation). For 2022, “Globally 91% of children who used World Literacy Foundation services showed improvements in their literacy skills. 78% of children who received books and reading support through their services showed positive changes toward healthy reading habits. They distributed 180,000 books as well as providing 8,400 hours of literacy support. They also produced 341 local language and bilingual books in 31 different languages as well as reach 180 million people with information about the importance of reading and awareness of literacy in their communities. Every 3 seconds in 2022, a child or young person used one of the World Literacy Foundation’s educational resources or services. Lastly, they provided literacy intervention in 54 countries including Columbia reaching 840,000 children through their Youth Ambassadors program and literacy partners” (World Literacy Foundation Impact Report 2022) which include Noble Projects Literacy Candle Company, Atmosphere Press Company, Pitney Bowes technology company, Pura Vida bracelets company, Vizrt software company, Harry Moon book series, Mr. Wordsmith stationary products in Melbourne, Australia, and Fable online books company (World Literacy Foundation.org).

The World Literacy Foundation has set Millennium Development Goals in 2000 to ensure that “by 2015, children everywhere will complete a full course of primary schooling and to eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education by 2005 and in all levels no later than 2015” (World Literacy Foundation Final Report 2022). Some recommendations they are working towards are establishing adult and parental literacy programs, increasing attendance and retention rates in schools, providing resources, training, and technology to teachers, students, schools, and parents, and finally, raising awareness and finding financial support to combat illiteracy globally (World Literacy Foundation Final Report 2022).

The vision of the World Literacy Foundation in 2023 is to “see all women and children have access to literacy regardless of location or social status, to have all children experience the joy of reading and writing for the first time, to ensure the love and practice for literacy is shared and promoted around the world, to educate and instill the importance of literacy development in women and children to the wider community as well as openly invite everyone to join in their mission to change lives and make a global impact” (World Literacy Foundation.org).

One way that developing countries can make literacy education a priority is to fund early education programs that involve more hands-on learning through play, train teachers and teaching assistants in different types of literacy curriculums for different age groups and learning styles, provide more resources to parents and caregivers in different languages to practice literacy activities with the children at home (i.e. books, games that involve singing and dancing, having conversations with their children, etc.), and lastly work with different national and local organizations to gain more information about the importance of literacy not only in their country but in their communities and eliminate literacy globally. The World Literacy Foundation would like to achieve this goal by 2040. If we stay on track with making small impacts each year in Latin America and around the world, I believe that not only the World Literacy Foundation but other literacy and government organizations that exist and are created in the future will help make a difference in the lives of boys and girls through literacy.

References:

- Caribbean, E.C. for L.A. and the. (2020, July 21). Illiteracy Affects Almost 38 Million People in Latin America and the Caribbean. www.cepal.org. https://www.cepal.org/en/news/illiteracy-affects-almost-38-million-people-latin-america-and-caribbean

- United Nations Statistics Division. (2019). – SDG Indicators. Un.org. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/goal-04/

- Why Literacy- World Literacy Foundation. (n.d.)/ Worldliteracyfoundation.org. https://worldliteracyfoundation.org/why-literacy/

- Changing children’s lives in Columbia through the power of literacy. (n.d.). Retrieved March 16, 2023, from https://worldliteracyfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Brief-Aprende-Leyendo-2021-ENG-1_compressed-1.pdf

- World Literacy Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved March 16, 2023, from https://worldliteracyfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Impact-Report-2023V2.pdf

- The Economic and Social Cost of Illiteracy: A Snapshot of Illiteracy in a Global Context. (n.d.). Retrieved March 16, 2023 from https://worldliteracyfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/The-Economic-Social-Cost-of-Illiteracy-2022.pdf

No Girl Left Behind

Over 129 million women and girls are excluded from education worldwide (UNICEF, 2019).

Education plays a vital role in society. Particularly, access to secondary education creates significant economic growth and development. Investing in education directly affects growth, health, and infrastructure, which contributes to the success of society (The World Bank, 2018). According to the World Bank, education not only promotes human development in areas such as increased health and poverty reduction, but it increases employment, creates innovation, strengthens institutions, instills social cohesion, and drives long-term economic growth (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2011).

The importance of access to secondary education is crucial. If every child had access to secondary education, the child mortality rate for children under five would fall by 49%, individual income would increase by roughly 10% each school year attended, and early pregnancies would decrease by 59% (Cahill, 2019). Additionally, there would be a significant decrease in child labor and gang violence (Buechner & Su, 2022). Most shockingly, according to UNESCO, if all children completed secondary school, the global poverty rate would be cut in HALF (2017). Secondary education not only helps society advance economically, but it also increases the overall health and happiness of a population – which is essential for the prosperity of a people.

So what happens when half (if not more) of that population is left out?

Wouldn’t that mean: half as much growth, development, and prosperity?

Correct.

Women and girls are at the forefront of gender inequality in education.

In 1948 education was declared a human right in article 26 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2011). Today, that right is still not guaranteed. Women and girls remain negatively affected by the implementation of laws and policies that prohibit or restrict them from access to education.

Research shows that growth and development flourish when girls have access to secondary education. Access to education for women and girls (Cahill, 2019):

- Reduces child marriage, child/maternal mortality rates

- Allows them to attain higher-earning jobs/become self-sufficient

- Empowers them to make their own choices

- Increases their participation in society

- Creates peaceful social interactions

Restricted access to education forces girls to rely solely on the male population for economic and social security. This results in earlier, increased child marriages and higher birth rates (Delprato, 2022). Educating girls equally reduces gender norms that drive boys to drop out of school to earn an income and support a family. Keeping children in schools reduces child labor and gang violence (Buechner & Su, 2022).

While there has been a movement toward gender equality in secondary education, millions of girls are still not enrolled in formal education (UN Women, 2022).

What is being done?

In 2015, the United Nations created the sustainable development goals (SDGs). These are a call to action by 2030 to have the world enjoy peace and prosperity (United Nations Development Programme, 2023). SDGs 4 and 5 focus on access to quality education and gender equality. These goals aim to ensure inclusive and equitable education for all while achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls. Major targets of these goals emphasize ending discrimination against women and girls and ensuring all children complete primary and secondary education with effective, quality learning (United Nations, 2022).

While there have been significant increases in access to education, and we are seeing more girls in school now compared to 15 years ago, significant inequalities still exist off-paper (United Nations Development Programme, 2023). In many places where education is “allowed” for girls, they still face gender-based violence on the way to school and within school buildings. In addition, many countries underreport gender parity in their education systems, and when school is in session, how much quality learning is really taking place (Human Rights Watch, 2017)?

If one girl is left behind, significant gaps exist in a nation’s development and, in turn, the world’s development (UN Women, 2022). With advances in education technology (EdTech), education is becoming more easily accessible. The benefits of this must be realized to end this deeply rooted inequality.

Governments worldwide need to take the correct steps to realize the right to equal education. They can create policies to ensure that local governments, communities, and people work together to assist children in the fight for equal, accessible education. With international assistance, governments can build better infrastructure, train teachers, and implement strategies that work to end discrimination (Human Rights Watch, 2017). These issues must be addressed and adjusted for a more productive and peaceful society.

References

Buechner, M., & Su, T. (2022, September 2). 10 Reasons to Educate Girls. Retrieved from UNICEF USA website: https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/10-reasons-educate-girls/40311#:~:text=Girls%20who%20complete%20a%20secondary

Cahill, A. (2019, August 28). The Importance of Secondary Education. Retrieved from The Borgen Project website: https://borgenproject.org/the-importance-of-secondary-education/

Delprato, M. (2022, February 2). Education can break the bonds of child marriage. Retrieved from World Education Blog website: https://world-education-blog.org/2015/11/18/education-can-break-the-bonds-of-child-marriage/

Human Rights Watch. (2017, October 17). “I Won’t Be a Doctor, and One Day You’ll Be Sick” | Girls’ Access to Education in Afghanistan. Retrieved from Human Rights Watch website: https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/10/17/i-wont-be-doctor-and-one-day-youll-be-sick/girls-access-education-afghanistan

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. (2011). Learning for All. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/27790/649590WP0REPLA00WB0EdStrategy0final.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The World Bank. (2018). Overview. Retrieved from World Bank website: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/overview

UN Women. (2022, October 11). Leaving no girl behind in education. Retrieved from UN Women – Headquarters website: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2022/10/leaving-no-girl-behind-in-education#:~:text=Worldwide%2C%20nearly%20130%20million%20girls

UNESCO. (2017). Reducing global poverty through universal primary and secondary education. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Retrieved from https://uis.unesco.org/en/files/reducing-global-poverty-through-universal-primary-secondary-education-pdf

UNICEF. (2019). Girls’ education. Retrieved from UNICEF for every child website: https://www.unicef.org/education/girls-education

UNICEF. (2022). Secondary Education. UNESCO Institute of Statistics Global Database. Retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/secondary-education/

United Nations. (2022). Goal 4 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved from sdgs.un.org website: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4

United Nations Development Programme. (2023). The SDGs in Action. Retrieved from UNDP website: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals/gender-equality