By Óscar Cejudo Corbalán

Tomás starts talking aggressively to another kid who answers in the same manner. The conflict rapidly escalates and shifts from verbal to physical violence. Luckily, the teacher was close enough to stop the fight before it got serious (we all know what could potentially happen next when the teacher scolds Tomás, but that is another story.)

Violence calls violence, and peace calls peace. It seems obvious to me; I could say it is a principle that I hold dear. This is not only at an interpersonal level, but also at the international one. I have always criticized military interventions that seek peace (and I would probably still criticize them.) Specifically talking about armed conflicts where the spiral of conflict leads to deadly outcomes.

That is why Kelly McMillin’s session was so insightful for me, because it brings the reality I was missing by talking about armed conflicts from the comfort of my town in Spain or in academia here in the US. He talked from the experience of a former Chief of Police (among many other ranks previous to that, and more identities/social statues he holds) about gang violence in Salinas.

Once you leave the theoretical field (and the security that comes with it) and get to the practice, in context such as these ones, the idealism of facing the conflict without counter measures of a similar caliber crumbles. People (gang members, other civilians, peacebuilders, etc.) are in real danger to be killed, and sometimes direct violence is the only way to stop that from happening. Then the questions that come to my mind are: can violence stop violence? And more specifically: can some types of violence be stopped without violence?

My answer would be no to both. Starting with the second question, this might be what I got the most out of the session: it shifted my stand from thinking that intervening in an armed conflict bringing more weapons to the equation can only escalate the situation and therefore is counterproductive to resolve it (therefore we should not do it), to bringing the weapons in is many times the only way to guarantee staying alive and therefore is necessary (also to resolve it.) I know, I am typing this and it seems pretty obvious, but it clearly was not my stand beforehand, you can call it privilege or ignorance (if they are not synonyms.)

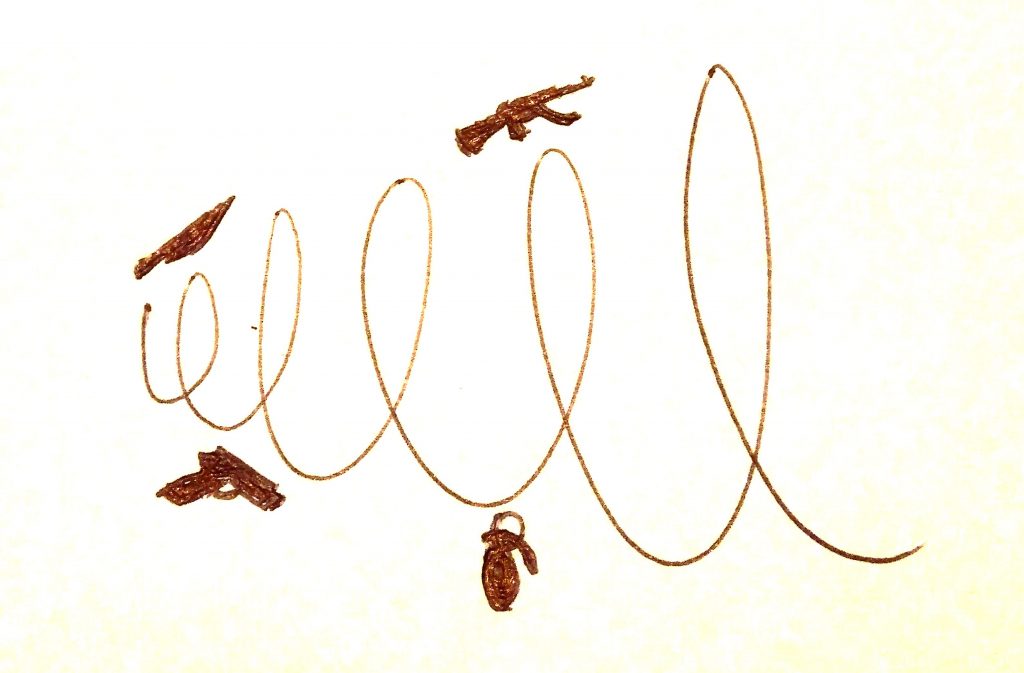

However (and this brings me to the first question), I still think violence cannot stop violence (this is even clearer when we are talking about structural violence.) There is actually this spiral of conflict growing and growing, perfectly represented in the case of gang violence with the arms race between gangs and law enforcement. As much as I got to understand the need of the presence of weapons in the “resolver’s side”, it is also clear that (as stated in the beginning) violence calls violence, and the use of force cannot bring sustainable and real peace.

This is where peacebuilding as a multidisciplinary and multirole approach becomes even clearer to me. Police can be (and I would say must be) peacebuilders; and if we were to consider (for the purpose of this blog) law enforcement as a discipline, then we could break it down into different roles. The use of violence/weapons when needed to ensure classic (and basic)security could coexist with community policing initiatives that will hopefully bring about a different type of security based on social capital.

Having policemen and policewomen building relationships with the people they serve, enhancing trust, brings law enforcement closer to tackle the root issues of gang violence, and definitely help them to better serve the community. It is another type of security, a more sustainable one based on trust and social capital, one that does not need weapons to be maintained. Instead of a violent security based on the use force/weapons, they are building a peaceful security based in relationships. (It is interesting to see how these violent and peaceful securitiesrelate to Galtung’s negative and positive peace, respectively.)

I started this blog with the idea of concluding that I now understand that many conflicts will actually need the use of a violent countermeasure that will allow any other type of approach to happen (which I honestly do). But, focusing on the law enforcement vs. gang case, let me draw another conclusion (or raise another question): what if we are witnessing the development of a new understanding for law enforcement? What if this is the inevitable evolution of dealing with gang violence?

It is very interesting to me to imagine it as a natural evolution of law enforcement that goes hand in hand with the evolution of the field of peace and conflict studies: from a conflict management approach (by the use of force and violence) to a conflict transformation approach that seeks to change relationships. But probably I am still being too idealistic, privileged, or ignorant.