By Kaitlynn Pimentel

Indonesia is the 4th most populated country in the world, home to 260 million people, but the success of the country is being stunted by their alarmingly high unemployment rate. The country is experiencing a youth bulge, with half of the population being aged 28.6 years or younger (Indonesian Investments, 2017). Currently, 5.8% of the Indonesian population is unemployed; which is abnormally high, as pre-pandemic unemployment rates were only 4.9% (World Bank, 2022). According to the Social Monitoring and Early Response Unit Institute (SMERU Institute), about 1/3rd of those unemployed are youth, ages 15 to 30 years old, and the percentage of unemployed youth. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were drastic- between August 2019 and August 2020- youth employment increased from 13.03% to 15.23% (SMERU Institute, 2021).

In addition to a high unemployment rate, Indonesia grapples with extreme poverty. According to the World Bank, about 167.8 million Indonesians live on less than $7.00 per day, with 62 million Indonesians living off of less than $4.00 per day, and a staggering 9.8 million Indonesians living beneath the international poverty line of $2.15 per day.

Indonesia is a patriarchal society, attempting to create equality between men and women; however, women in Indonesia only “earn 59.27 percent of what their male counterparts with the same level of schooling bring home” (Jakarta Post, 2022). According to the World Economic Forum (2022), Indonesia is ranked in 92nd place out of 146 countries in the global gender index which is much lower than it’s nearby south asian countries such as the Philippines who placed an impressive 19th out of 146 countries.

Based on my research, I believe that in order to improve unemployment, poverty, low access to education, and gender inequality- government agencies need to implement a creative and empowering form of education: Entrepreneurship Education. Firstly, Entrepreneurship education when using project-based, practical, and interpersonal teaching strategies creates a guided path for young people to create income for themselves and reduce the local and national unemployment rate (Olajide, et.al, 2014). In addition, “there is strong empirical evidence suggesting that economic growth over time is necessary for poverty reduction and entrepreneurship boosts economic growth,” (Mitra & Abubakar, 2011). Finally to address gender inequality, a researcher by the name of Esra Sena Türko (2016), who works teaches a Erzurum Technical University in Turkey studied the effects of entrepreneurship education on gender inequality, and found that it can reduce discriminatory gender stereotypes, especially concerning negative notions of women as business owners or sole income earners.

I am not trying to argue that Entrepreneurship is a cure-all for developing countries and conflict; however, my research and experience working with development NGO’s in rural Bali has shown me that by giving individuals access to entrepreneurship training and resources- they can not only improve their ability to generate income and job opportunities for their communities, but they can also solve complex social problems via social entrepreneurship (Rae, 2010).

The government of Indonesia acknowledges the use of entrepreneurship education as a vital role in their development and reduction of unemployment, and has been creating programs and policies to increase entrepreneurship in the country. The program that I researched was the JAPRI program which stands for JAdi Pengusaha MandiRI (Become an Independent Entrepreneur). This program was funded by the USAID and managed by IIE Indonesian team in order to offer short-term training programs to women, youth, and individuals with disabilities followed by a 6-month mentorship and coaching program to help assure the longevity of the training impact. The program began in April 2017 and concluded in April 2022 with a successful reporting of 19,744 youth women and disabled individuals completing entrepreneurship training, over 4,000 new businesses created, and over 600 community members and university lecturers becoming JAPRI business coaches (JAPRI Report). The program partnered with local governments, Indonesian NGO’s, and Universities to develop and implement localized training as well as connect local coaches and mentors.

I had the honor of speaking with David Simpson, the liaison and lead administrator for the JAPRI program. He spoke about the vision of the program which was essentially to use the tools and resources in entrepreneurship to offer poor and vulnerable populations in Indonesia a sustainable way to get out of poverty. He discussed how entrepreneurship is especially impactful because it creates a positive chain reaction of job creation and economic opportunity in Indonesian communities. Simpson highlighted the importance of working with national and local governments, as well as local NGOs and Universities. He said the JAPRI program was designed with collaboration in mind, and that is why it was so successful.

I posed the following question to David: “If I were going to develop a small scale entrepreneurship education program for youth ages 15 – 30, what should I do differently than the JAPRI model?”. Simpson advised me to include more emphasis on financial literacy education as well as resource maps for entrepreneurs to finance their SMEs through existing Indonesian loaners and banks. He also talked about the importance of reaching rural communities. The JAPRI program was primarily administered on the Island of Java, which is home to the nation’s capital (Jakarta) and about 60% of the Indonesian population; however, this leaves the remaining islands of Indonesia falling further and further behind. Simpson ended our conversation by encouraging NGO’s to implement entrepreneurship training because it is a key focus of the government’s development plan, but officials simply don’t have the resources and funding to maintain quality assurance across the thousands of Indonesian Islands.

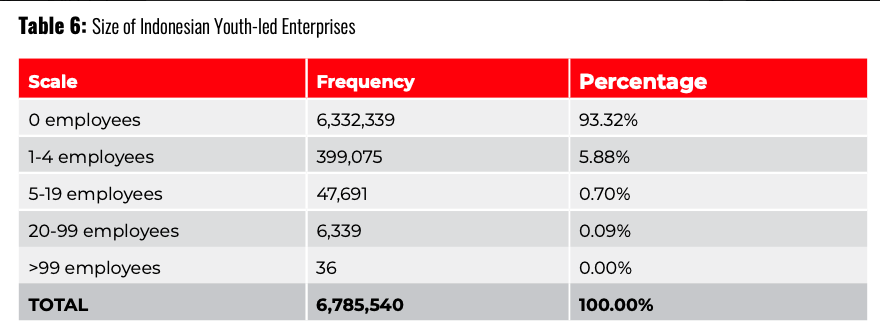

After my delightful conversation with David Simpson, I did some research into what the current entrepreneur ecosystem looks like in Indonesia. According to Kompas, I found that only 3.47% of the Indonesian workforce are entrepreneurs, which is relatively low compared to Indonesia’s neighboring countries such as Thailand (4.26%), Malaysia (4.74%) and Singapore (8.76%). Indonesia has the goal of growing their entrepreneurship rate to 4% by 2024. In regards to youth entrepreneurship, I found larger participation rates in Entrepreneurship, with about 19.90% of Indonesian youth creating their own enterprises. It is important to note that the majority of Indonesian youth entrepreneurs work alone (SMERU Institute, 2021). The remaining breakdown of youth-led led enterprises is shown in the graph below:

From this report, it should be made clear that Entrepreneurship is not only a powerful tool to fight against injustice and unemployment in Indonesia; but also, that the local and national governments in Indonesia are well aware of the benefits of Entrepreneurship Education. From my personal experience working in Indonesia- I have seen the implementation of Entrepreneurship at the University level, but with such a low percentage of Indonesians attending University- I believe we must implement it at a much earlier stage in education.

Below are my recommendations for Entrepreneurship Education Programs in Indonesia based on my research and informational interview with IIE’s David Simpson.

- Partner with local governments and NGO’s to create an education program for entrepreneurship.

- Use local examples of successful entrepreneurs as inspiration and long-term mentors for program participants.

- Ensure special parameters to meet the needs of women and those with disabilities who face inequality in Indonesia.

- Apply the program to rural regions in Indonesia.

- Provide pathways to financing resources and market access.

- Include financial literacy training, especially for the poor and vulnerable populations.

References:

Simpson, David. Telephone Interview, March 1, 2023. Interview conducted by Kaitlynn Pimentel.

Juliastuti, Anna. (2022, April) Jadi Penguasha Mandiri Final Report. Institute of International Education. https://www.iie.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/USAID-JAdi-Pengusaha-MandiRI-JAPRI-Program-Final-Report-April-2017-April-2022.pdf

Mitra, Jay & Abubakar, Yazid & Sagagi, Murtala. (2011). Knowledge creation and human capital for development: the role of graduate entrepreneurship. Education + Training. 53. 462-479. 10.1108/00400911111147758.

Moberg, K. 2014a. Assessing the impact of Entrepreneurship Education – From ABC to PhD. Doctoral Thesis, Copenhagen Business School.

Oluwafemi, Christianah Oluwabunmi, Martins, O. Rebecca, Adebiaye, H. Olajide

6 April 2014. Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development.

https://core.ac.uk/display/234695092?utm_source=pdf&utm_medium=banner&utm_campaign=pdf-decoration-v1

Pape, Utz Johann. (2022, October) Poverty & Equity Brief Indonesia East Asia & Pacific. The World Bank. https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-750588BF00QA/current/Global_POVEQ_IDN.pdf

Population of Indonesia. Indonesian Investments. https://www.indonesia-investments.com/culture/population/item67

Rae, D. 2010. Universities and enterprise education: responding to the challenges of the new era. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 17, 591-606.

Safitri, Kiki. (2021, May). Pemerintah Targetkan Rasio Kewirausahaan Indonesia 4 Persen. Kompas.

Share of Indonesian population over 15 years old in 2022, by highest education level (2023, January). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1298842/indonesia-share-of-population-by-highest-education-level/

Tamyis, Ana Rosidha; Widyaningsih, Dyan; Fatah, Akhmad Ramadhan. (2021) UNDP and IsDB. The State of the Ecosystem for Youth Entrepreneurship in Indonesia. https://smeru.or.id/en/publication/state-ecosystem-youth-entrepreneurship-indonesia

Türko, Esra Sena (2015). Can Entrepreneurship Education Reduce Stereotypes Against Women Entrepreneurship? Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Erzurum Technical University, Erzurum, Turkey Received: May 23, 2016 Accepted: June 26, 2016 Online Published: October 26, 2016 doi:10.5539/ies.v9n11p53 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ies.v9n11p53

World Economic Forum. (2022). Global Gender Gap Report 2022. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2022.pdf

Yuniar, Resty Woro. Indonesians are made to choose between food and school fees as inflation hits poorest hardest (25 September, 2022). South China Morning Post.