“Since I was a child, my parents instilled in me the importance of pursuing a nursing career in order to make a decent living and to move to the States. It was never really my dream, but I had a duty to fulfill. I had no prospects in the Philippines either way, so I had no choice but to move. It was because I had “utang na loob” (to be greatly indebted to another) for my family.”

This is a story shared by a University of The Philippines, Diliman alumni, and current RN at the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula, known as S.M. Hence, just like S.M., within the context of poor economic conditions, very limited high-income opportunities for Filipinos and the desire of children to help or “give back” to their families, many Overseas Filipino Workers, called OFWs, pursue college degrees or vocational training in order to work as healthcare workers overseas (Lorenzo, 2007), education, hospitality, engineers, general work, IT professionals, etc. (Digido, 2023).

The Creation of “Migrant Schools” and Market-Driven Curricula in Philippine Higher Education Institutions

Kidjie Saguin from the University of Amsterdam, in his study of the de-privatization of higher education institutions (HEIs) in the Philippines, correlates the Philippines’ economic ambitions and the re-centralization of government in the 1970s with the prevalent disparities in educational attainment, selective growth of certain educational programs, and the mass emigration of Filipino professionals, leading to the present labor gap crisis. With a growing demand for migrant workers in sectors such as healthcare and business abroad and coupled with a tight labor market domestically, the Philippine administration under Ferdinand Marcos heavily subsidized HEIs with a supplementary mandate to meet the standards of the Overseas Employment Program the administration established as part of a development program to increase GDP via remittances and to lift labor market strains (Saguin, 2023). As a result, Philippine HEIs transformed into what Saguin calls “Migrant Institutions.” Consequently, the key characteristic of some Philippine tertiary education in both private and public schools, notably nursing in this case, became the flexibility of its curricula designed to predict labor gaps in migrant destination countries and meet these labor demands abroad (Ortiga 2017, 490).

However, the de-privatization of HEIs in 1972 led to a divide in the quality and accessibility of tertiary education. Private institutions established selective curricula, often designed with elite and niche courses such as professional development and advanced medicine (Saguin 2023, 477). Public HEIs, on the other hand, experienced a massification phenomenon following the heavily subsidized higher education system, wherein students who have intention to work abroad are trained to obtain professional licenses in market driven courses such as nursing and business administration. On the other hand, non-competitive, alternative courses such as the social sciences produced no significant financial return to society and employment attainability, and therefore became underfunded and unpopular (Saguin, 478). Therefore, while enrollment has followed a general upward trend, the number of graduates has remained more constant, or even declined in some traditional disciplines, such as Humanities, Social Sciences, and the Arts (Battistella & Liao, 2013).

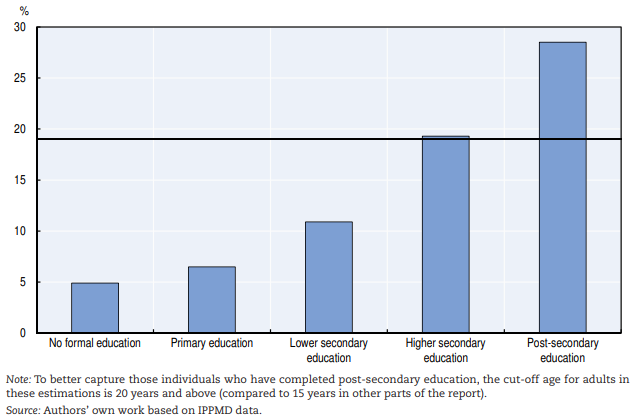

Figure 1: Highly educated individuals in the Philippines that are more likely to plan to emigrate

Examining the Quality of Nursing Programs in Philippine HEIs

Among other HEI programs, a growing demand for healthcare professionals and nurses abroad has led to a significantly higher enrolment in medical and nursing degree programs in Philippine HEIs (OECD/Scalabrini Migration Center, 2017). Thus, given this demand, the quality of academic healthcare programs increased.. A study conducted by Stella Appiah analyzed the quality of Philippine nursing education based on the following criteria: objectives and mission statements, curriculum and instruction, administration of nursing education, faculty development programme, physical structure and equipment, student services, and admission of students and the quality assurance system (Appiah, 2020). Almost 200 nursing faculty from 15 institutions participated in the study. Appiah’s study concluded that the quality of nursing programmes was perceived to be consistently high (a mean score of 96%). Therefore, well-trained graduates are in high demand on the international market and work overseas for higher salaries.

Conclusions and Recommendations

It can be observed that emigration-oriented and market-driven education, with centralized regulations and support from government subsidies, as well as limited opportunities for high income at home (Lorenzo, 2007) has led to the increased emigration of professionals. Nurses are motivated to move abroad by comparatively higher wages which support their family and themselves. This has created a feedback loop: The Philippines has continued to excel in its world renowned nursing programmes, with its top universities producing and sending out competent graduates both in the field of medicine to institutions all over the world (Appiah 2020).

But is this truly progress? According to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Goal 4, the answer is no.

The migration of the nation’s professionals and critical healthcare workers have resulted in a decline in human capital investment, commercialized health education and its attainability, and has caused a nation-wide depletion of skilled learning facilitators (Castro, 2017). Investing in human capital is a key component of achieving SDG 4. If higher education is selective and emigration-driven, this hinders growth as the returns to investment in education do not circulate domestically, but abroad. As a result, receiving countries are absorbing the highly valued skills and knowledge of Philippine professionals and healthcare workers. While migration has been seen by some as an opportunity for professional growth and enhancement and as a window for drafting more effective national and intercountry policy responses to HRH mobility (Castro 2017), a report conducted by the Scalabrini Migration Center concluded that return migration does little to build human capital since few emigrants acquire education abroad, nor do return migrates have economic incentive to return home with the pressurized labor market and lower value added to the domestic labor workforce as a prominent issue (OECD/Scalabrini Migration Center 2017).

Given the present state of the domestic healthcare system and the decreasing number of healthcare workers in the Philippines (brought about by their exodus to other countries), Philippine government policymakers should consider raising wages and social benefits for nurses and professionals to seek employment domestically upon graduation. Investing in training healthcare workers in rural and urban areas with local contexts and practices are equally as important in improving the domestic labor market. One primary example is a Public Health Leadership Development program that the University of the Philippines, Manila College of Nursing conducted in 2019 and ended in 2022, wherein 183 public healthcare workers from 17 regions, but rural and urban, participated in training courses that simulated local conditions and applied the Benner’s 5 Levels of Leadership Competencies as a metric of success (Tomanan et al., 2022). The design of this leadership training program, which required the participation of local and national government units, was to adapt to the demands of the Philippines’ health care constituency, leading to a better access to healthcare for a lot of Filipinos. Although further reports of its success are inaccessible publicly, this provides a valuable model in empowering rural healthcare workers and improving the quality and accessibility of healthcare education and training.

References

Appiah, S. Quality of nursing education programme in the Philippines: faculty members perspectives. BMC Nurs 19, 110 (2020).

Battistella, G., & Liao, K. A. S. (2013). Youth migration from the Philippines – Sustainable Development Goals Fund. https://www.sdgfund.org/sites/default/files/Youth-Migration-Philippines-Brain-Drain-Brain-Waste.pdf

Castro-Palaganas, E., et al. (2017). An examination of the causes, consequences, and policy responses to the migration of highly trained health personnel from the Philippines: the high cost of living/leaving—a mixed method study. Hum Resour Health 15, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0198-z

Digido. (2023, September 18). Top 10 in-demand jobs abroad for Filipinos: 2023. https://digido.ph/articles/ofw-loan/in-demand-jobs-abroad

Kidjie Saguin (2023) The Politics of De-Privatisation: Philippine Higher Education in Transition, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 53:3, 471-493, DOI: 10.1080/00472336.2022.2035424

Kristine Joy L. Tomanan, RN, MCD, John Joseph B. Posadas, RN, MSAHP, Miguel Carlo A. Fernandez, RN, Peter James B. Abad, RN, Msc, and Sheila R. Bonito, RN, DrPH, Tomanan, K. J. L., Posadas, J. J. B., Fernandez, M. C. A., Abad, P. J. B., & Bonito, S. R. (2022). Building Capacities for Universal Health Care in the Philippines: Development and Implementation of a Leadership Training Program. Philippine Journal of Nursing, 92(2). https://doi.org/http://www.pna-pjn.com/

Lorenzo, F. M. E., Galvez-Tan, J., Icamina, K., & Javier, L. (2007, June). Nurse migration from a source country perspective: Philippine Country Case Study. Health services research. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1955369/

OECE ilibrary. Migration and education in the Philippines. 2017 (137-157). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264272286-10-en.pdf?expires=1612566300&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=38B6DA2EC8F70C1B5B884A2DBE9309C1

Ortiga, Y. (2017). The Flexible University: Higher Education and the Global Production of Migrant Labor. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1113857