Empowering Change: MCE Social Capital’s Role in Advancing Financial Education in El Salvador

(MCE Social Capital, 2023a)

Some of the most significant challenges in providing education programs, especially in remote areas, center around issues of access and availability. According to a study by the World Bank, utilizing existing local institutions in delivering programs, such as those for financial education, can be an effective way to address issues of access, particularly in regions with marginalized and disadvantaged populations (Agrawal et al., 2008). In El Salvador, many programs for financial education are provided by local institutions and organizations who strive to bring services to underrepresented populations. Grassroots efforts are well situated to connect with local communities where trust and relationships with the local population have already been established, however, these efforts frequently grapple with inadequate resources.

To bridge the gap between intention and execution, MCE Social Capital (MCE), a nonprofit impact investing firm, leverages its innovative loan guarantee model to support enterprises that drive sustainable livelihoods in emerging markets. Their mission prioritizes financial inclusion, offering economic opportunities and empowerment, particularly to women in developing economies, furthering international development goals including gender equality (SDG5) and reduced inequalities (SDG10) (MCE Social Capital, 2023b). To achieve financial inclusion, it is essential to provide education in financial literacy, a skill that must be systematically taught (AFI, 2023). Funding programs that incorporate financial education, such as those backed by MCE, can therefore facilitate increased economic participation and pave the way for sustainable development.

Partnerships for Progress

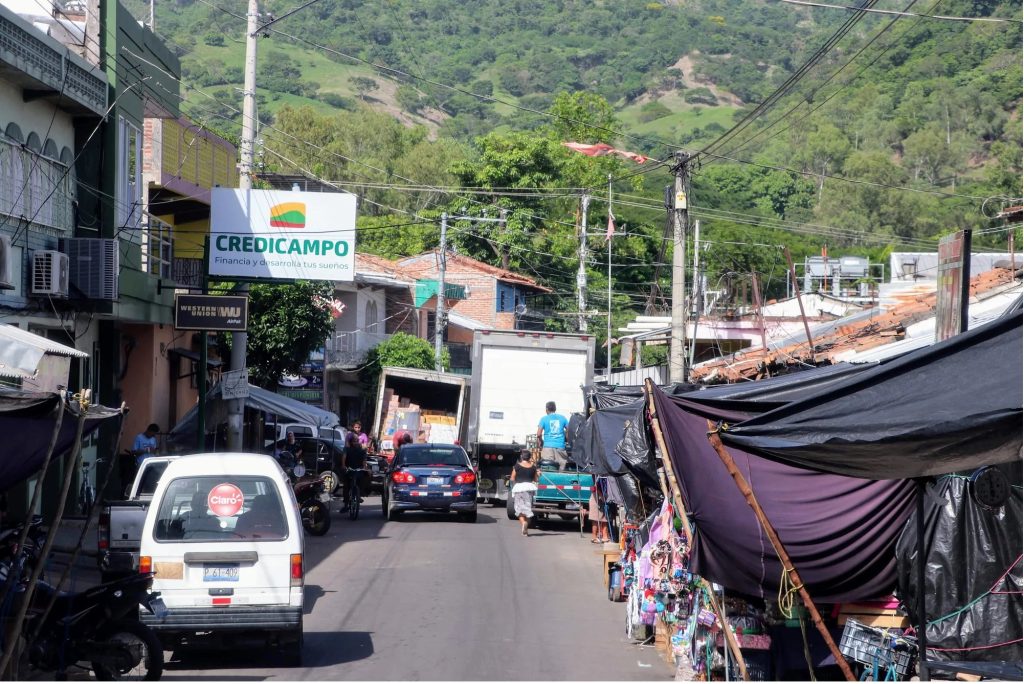

Operating across the globe, MCE collaborates with local organizations to provide services to their communities in the quest for international development. In El Salvador some notable examples are the NGO ASEI in San Salvador, empowering low-income entrepreneurs through financial education and small loans, and CrediCampo, a cooperative whose community development services include financial education and literacy programs (MCE Social Capital, 2023a). There is growing support in the country for this type of education, and institutions like these are in the best position to reach the populations most in need of these skills. Organizations like MCE provide the resources needed to make these programs possible.

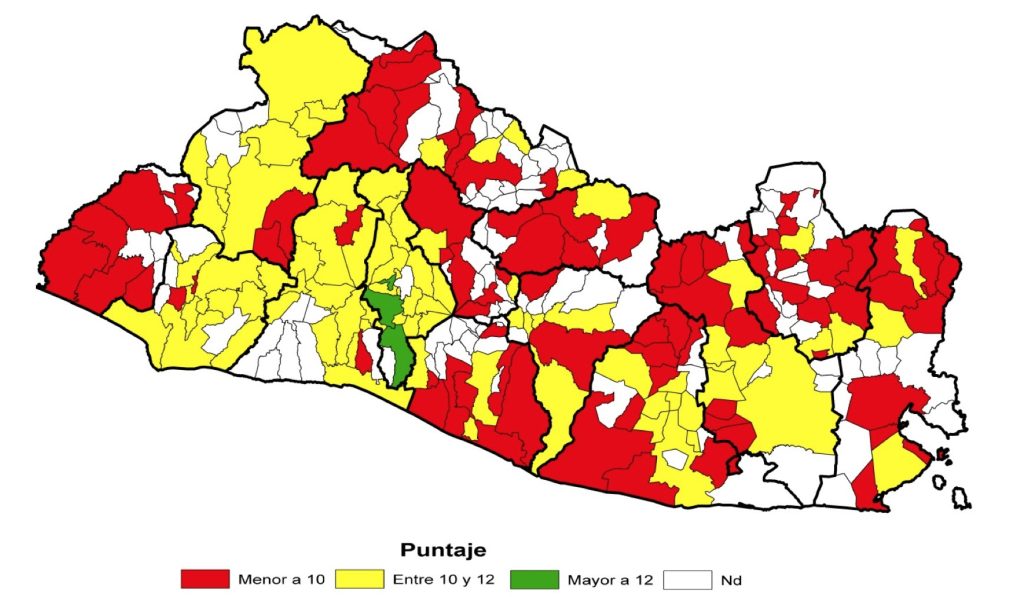

Target Areas for Financial Education Programs

Scale of 1 to 20 points, with 1 being no literacy and inclusion and 20 being full literacy and inclusion

(AFI, 2016)

Impact in Numbers

El Salvador has been working to expand these programs as financial literacy has become a priority. Understanding that the requirements for economic growth and socioeconomic equality include developing the skills and confidence necessary for Salvadorans to make informed financial decisions, a nationwide Financial Education Program (FEP) was established in 2008 (AFI, 2016). MCE partnership with CrediCampo in the Morazan Department is representative of this national policy. A 2019 statement by the president of CrediCampo’s communal credit committee, Elvis Estella Vazquez de Flores, emphasizes that financial education is “one of the most important aspects” of their member relationships (MCE Social Capital, 2019). Elvis is correct in her assessment. Financial education programs in El Salvador are directly attributed with the 14% improvement between 2016 and 2022 in the Financial Education Indicator (FEI), a measure used to assess the state of financial literacy (AFI, 2023). For women, this increase in financial education means greater autonomy and equity in traditionally male dominated societies empowering them to take control of their own lives and well-being (Sen, 2023). CrediCampo is proud to prioritize women who make up 46% of their membership (MCE Social Capital, 2019). These steps toward development and equality prove the value this form of education can have to those who are most in need.

(MCE Social Capital, 2019)

MCE has made a total of four loans to CrediCampo in El Salvador and continues to provide funding for their ongoing efforts to help maintain access to these programs. The achievements these organizations have contributed to, such as the improved FEI, should be recognized and encouraged, but there is still a long road ahead. As of the latest figures in 2022 for El Salvador, 35.8% of women still do not have incomes of their own, compared with 11.7% for men. The average in Latin American countries is somewhat better with 27.6% of women and 11.2% of men still lacking independent incomes (ECLAC, n.d.). Financial education programs are still greatly needed and organizations like MCE are, in part, to thank for the progress made thus far.

Continuing Development

The impact of MCE Social Capital and its partners is not confined to El Salvador or even Latin America. In 2022 alone, their efforts enabled over 383,000 individuals to receive financial education, with women representing over 60% of this group (Impact, 2022). While access remains a significant barrier to education worldwide, organizations like MCE, who provide funding to these organizations, play an important role in sustaining development-oriented educational programs. Targeted financial education can be a powerful tool in empowering communities and fostering equitable growth, however, the need for such education is far from met. As we continue to witness the transformative power of financial education in underserved communities, the path forward requires broader engagement and support to extend these benefits more widely.

- Agrawal, A., McSweeney, C., & Perrin, N. (2008). Mobilizing rural institutions for improving governance and development. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/11133

- AFI. (2023, February 21). Financial Education Takes Center Stage in El Salvador. https://www.afi-global.org/newsroom/blogs/financial-education-takes-center-stage-in-el-salvador/

- AFI. (2016, October 4). The Status of Financial Education in El Salvador: Using Evidence to Build Financial Capacity. https://www.afi-global.org/newsroom/blogs/the-status-of-financial-education-in-el-salvador-using-evidence-to-build-financial-capacity/

- MCE Social Capital. (2019, September 5). Purpose, capacity, and morality. Medium. https://mcesocap.medium.com/purpose-capacity-and-morality-ff860e59bf1

- ECLAC. (n.d.). People without incomes of their own. Gender Equality Observatory. https://oig.cepal.org/en/indicators/people-without-incomes-their-own

- MCE Social Capital. (2022). Impact. https://www.mcesocap.org/impact

- MCE Social Capital. (2023). Portfolio List. https://www.mcesocap.org/portfolio-list

- Sen, S. (2023, March 26). Economic abuse and the importance of financial literacy for women. https://www.rightsofequality.com/economic-abuse-and-importance-of-financial-literacy-for-women/

The integration of refugee children into national education systems for a more tolerant, cohesive society

Ola Pozor, International Policy & Development program

The all-time high number of refugee children in the world, 43.4 million and growing, (Ingram, 2023) speaks to the crisis-ridden era we live in and the urgency to provide children with quality education for a better future. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) specifies that refugee children are among those “who have been forced to flee conflict or persecution and cross international borders to seek safety”. Given the pressing issue of refugee children’s access to education, with “average enrollment rates at 38% at the pre-primary level, 65% at the primary level, and 41% at the secondary level” (UNHCR, 2023), the integration of refugee children into national school systems is a utmost priority among international organizations.

(UNHCR, 2023)

Integration for better access and inclusive global mindset

The obligation to provide primary education for refugees is stated in the 1951 UN Convention of Refugees, Article 22: “The Contracting States shall accord to refugees the same treatment as is accorded to nationals with respect to elementary education.” Since 2019, UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund, and its partners have shifted away from ‘parallel education systems’ (e.g. refugee camp settings), and have aimed to “find durable solutions for forcibly displaced populations geared toward inclusion into national systems” (UNICEF, 2022, p. 2). Thus, UNHCR and UNICEF have established country-specific offices and partnerships with national governments to prepare teachers, classrooms, and students for a more diverse, multicultural community and ‘side by side learning’ with host country students. UNICEF’s 2022 Children on the Move (CoTM): Inclusion in Education report explains how formative learning assessments, digital learning tools, remedial courses, and hiring refugee teachers for instruction in native languages, in countries like Uganda, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Sudan, Thailand, and Poland, “are helping enroll refugee children in schools and appropriate learning pathways, thus enabling them to transition to the national education system.” The modality of schooling varies from country to country, based on the host government’s policies, size of the refugee population, and availability of teachers/classrooms; ranging from fully in-person, online, day-shift, evening-shift, and hybrid learning environments.

UNICEF and national education systems’ goal is to not only better integrate and educate refugees, but also to foster greater tolerance, global-mindedness, and social cohesion of host country students with their new peers. “Approaches that build social cohesion help to overcome discrimination and bias against CoTM and support their inclusion and retention in education and learning locally” (UNICEF, 2022, xii). This reflects the UN’s long-held goals on education for tolerance, a key facet of quality education for all. The 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights, Article 19, affirms that “education should promote understanding, tolerance, and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups.” Similarly, Article 4 of the 1995 UNESCO Declaration on the Principles of Tolerance states:

“Education is the most effective means of preventing intolerance. The first step (…) is to teach people what their shared rights and freedoms are, so that they may be respected, and to protect those of others. It is necessary to (…) counter the cultural, social, economic, political and religious sources of fear and intolerance – major roots of violence and exclusion (…). This should help young people to develop capacities for independent judgment, critical thinking and ethical reasoning.”

Education that integrates both national and refugee youth is both a preventative and proactive strategy to include refugees in safe spaces, as well as to widen locals’ perspectives and welcoming attitudes toward populations fleeing conflict, violence, and persecution. Inclusive education also contributes to SDG Goal #16 – “Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” (UN, 2015).

Measuring outcomes: Quality education for social cohesion in blended schools

While “definitions of social cohesion vary across academic disciplines and between defining agencies, and the measurement of the concept is equally as wide-ranging” (McCollum, 2022), there is some consensus in the international development community. According to the UNDP (2007), social cohesion involves “a society where all groups have a sense of belonging, participation, inclusion, recognition, and legitimacy. (…) By respecting diversity, they harness the potential in their communities to grow together.” In 2022, UNHCR, World Bank, and FCDO commissioned 26 papers on social cohesion between refugees and host country citizens, using methodologies ranging from surveys of host nation citizens, lab-in-field games, social networking data, and sequential mixed methods to gauge the indicators of social cohesion (McCollum, 2022). In many of the studies, “scholars agree to certain key dimensions to measure social cohesion: trust in individuals, social participation, freedom from violence, and acceptance of diversity” (McCollum, 2022). UNICEF has also put forth 34 studies of integrated refugee learning to assess the social impact of their programs and identify areas for improvement.

While the report acknowledges that newly arrived refugee learners face risks, “including stereotyping and low expectations by teachers, bullying, and discrimination by staff or peers” (UNICEF, 2022, p. 19), the commissioned studies after time show several positive outcomes. For instance, increasing joint online schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic for refugees and local children in Nashatati, Jordan, “has positively impacted children and adolescents, with survey results demonstrating a 34% increase in the ability to deal with confrontation and not to resort to violence, and a 35% increase in willingness to play and work with students of different ages and nationalities.” (UNICEF, 2022, p. 34). In Turkey, using sport, recreation, art, and dance to unite students with different language capacities “has led to positive results in building a safer and more inclusive environment for CoTM.” (UNICEF, 2022, p 19). In Colombia, “enrolling both Colombian and Venezuelan children in Learning Circles remediation courses, designed to promote learning and empathy, conflict resolution, decision-making, and emotional self-regulation, has been key in avoiding xenophobia” (McCollum, 2022, UNICEF, 2022, p 26). Finally, a 2023 Council of Europe Resolution, “Integration of migrants and refugees: Benefits for all parties involved”, highlights how integration of refugees into educational and other public spaces “has promoted peace and social cohesion and subsequently decreased the cost of social conflict” (Hajdukovic, 2023).

There is still much work to be done to assess host country children’s attitudes toward their peers and vice versa, and while there are some small-scale studies assessing different integrated education models’ impacts on peaceful and inclusive societies, only time will tell as more of these programs unfold and more children are enrolled in host country schools.

Jordanian children and Syrian refugee children playing with Legos together through the Nashatati activity programme in local schools, designed to foster greater social cohesion (UNICEF, 2022).

Looking Forward

Integrating refugees into national education systems is a fairly new phenomenon in the international education realm and there is still little data to summarize global integration rates and overall impact on social cohesion and tolerance. However, country-specific programmes, reporting, and measurement of these SDG-16 related-outcomes, such as the ones above, sheds light on the potential for this approach to build more peaceful, tolerant societies, one classroom at a time.

Works Cited

Hajdukovic, D. (2023, March 15). Integration of migrants and refugees: benefits for all parties

involved. Council of Europe, Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced

Persons. https://rm.coe.int/integration-of-migrants-and-refugees-benefits-for-all-parties-involved/1680aa9038

Ingram, T. (2023, June 14). Number of displaced children reaches new high of 43.3 million.

UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/number-displaced-children-reaches-new-high-433-million

McCollum, K. (2022, November 16). Measuring social cohesion in contexts of displacement:

Do researchers agree? COMPAS School of Anthropology, Oxford University. https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/2022/measuring-social-cohesion-in-contexts-of-displacement-do-researchers-agree/

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (1995, November 16).

Declaration of Principles on Tolerance. UNESCO.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2022, February). Education, Children on the Move and

Inclusion in Education. UNICEF.

UNHCR. (2023, September 20). Five takeaways from UNHCR’s 2023 Education Report.

https://www.unrefugees.org/news/five-takeaways-from-unhcrs-2023-education-r

eport/#:~:text=The%20report%20reveals%20that%20average,percent%20at%20the%20tertiary%20level.

United Nations. (1951, July 28). Convention relating to the Status of Refugees.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-relat

United Nations Development Programme. (2007). Working Definition of Social Cohesion.

E-dialogue: Creating an Inclusive Society: Practical Strategies to Promote Social Integration. Division of Social Policy & Development. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/sib/inclusive_society/social%20cohesion.html

Migrating Professionalism: How Motivations to Migrate Can Impact Education in Developing Countries

An international demand for high-skilled professionals, as well as stronger investments in international studies and migrant economic assistance in receiving countries in the past decade has consequently developed a global chain of exchange, wherein developing countries have the opportunity to send their highly skilled labor force overseas, with the expectation of higher returns to the economy via remittance sending and improvements to human capital when migrants return. According to the OECD indicators of talent attractiveness for OECD countries, the top receiving countries are the United States, Canada, and Australia. According to data provided by the Brookings Institution, the United States has been experiencing a gradual shift from semi-advanced industries, such as semiconductors, telecommunications, and wired & wireless telecommunications carriers, to advanced technological and service sectors such as software publishing, information services, and the most significant growth has been in computer systems, design, and services. This is, in due part, caused by a global race to advance technological and capital-intensive industries, with China, South Korea, and Japan leading alongside the United States. As the Department of Defense (DOD), in its Fiscal Year 2020 Industrial Capabilities Report states,

“Today’s education pipeline is not providing the necessary software engineering resources to fully meet the demand from commercial and defense sectors, and resources required to meet future demands continue to grow“

(Department of Defense, 2021; 102)

There is, therefore, a positive trend in the number of foreign-born STEM workers in the U.S. to make up for this deficit and to compete with foreign competition. In fact, according to a study conducted by the American Immigration Council, between 2000 and 2019, the overall number of STEM workers in the United States increased by 44.5 percent, making up almost one-fourth (23.1 percent) of all STEM workers in the U.S (American Immigration Council, 2022).

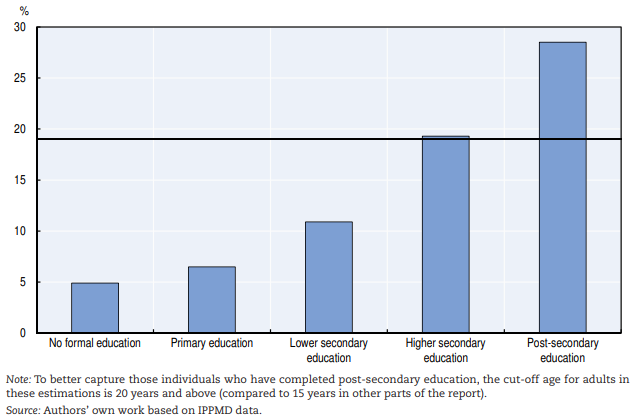

However, while OECD countries are benefiting from development in their advanced sectors through the increase in employment sourced from an increase in the acceptance of high-skilled labor from the Global South, sending countries stand to lose out and become vulnerable with a decline in professionals in health and services domestically. Shin and Moon explain this bottom-up global diffusion of highly skilled professionals using the discourse of brain circulation and brain linkage (Shin & Moon, 2018). These processes have undoubtedly contributed to greater interconnectivity between the developing countries and developed countries, opening opportunities to access higher education and careers in advanced sectors available and in-high demand in receiving countries. However, least developed countries (LDCs) are vulnerable to a domestic drain of human capital, or brain drain (Shin & Moon, 2018). Consider Figures 1 and 2 provided by an OECD report on Migration-Led Development in 2017: comparing the net enrolment rates (Figure 1) and share of individuals with post-secondary education who plan to emigrate (Figure 2), it can be observed that enrolment rates and the motivation to emigrate are positively correlated. For example, it can be seen in Figure 1 that the Philippines is among the highest of the 10 sample countries with the highest enrolment retention whilst also having the highest ratio of individuals with post-secondary education with intentions to migrate observed in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Net enrolment rates in primary education and mean years of schooling vary in the ten partner countries

Source: Enhancing migration-led development by facilitating investment in education | OECD iLibrary

Figure 2: Individuals with post-secondary education are more likely to plan to emigrate

Source: Enhancing migration-led development by facilitating investment in education | OECD iLibrary

A separate study conducted by the Scalabrini Migration Center on the Philippine migrant labor force concluded that health workers and highly trained professionals were the most prominent group of the labor force to emigrate (See Figure 3). According to the IPPMD Philippine questionnaire, on average, 19% of all individuals in the sample are planning to emigrate, compared to 29% of individuals with post-secondary education (OECD 2017; 140).

Alternatively, Burkina Faso has the lowest enrolment retention, as well the lowest ratio of individuals with post-secondary education with plans to emigrate (OECD/Scalabrini Migration Center, 2017).

Figure 3: The health sector and highly skilled occupations are losing more workers to emigration

Source: Migration and the Labour Market in the Philippines, OECD Ilibrary

By analyzing these figures, the relationship between education development, especially tertiary education in LCDs and developing countries and the trend in emigration outflows cannot be ignored. Southeast Asia and developing countries in East Asia such as India and China are the forerunners of this migration-led education development model (ASEAN-Australia, 2023). Despite these ambitions and the provision of resources such as scholarships and visas from receiving countries, there remain substantial barriers to achieving equitable education attainment domestically between ASEAN member states and the greater East Asian region, as knowledge and skills sets are sent abroad to fill the needs of demand.

The Case of the Philippines

The Philippines has been the leading country of origin of foreign-trained nurses in many OECD countries, including New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. A tight domestic labor market and low employment opportunities have drawn Filipino citizens to seek employment in other countries where labor supply is scarce and wages are comparatively higher. In his study of the de-privatization of Philippine education, University of Amsterdam professor Kidjie Saguin states that in order to depressurize the labor demand domestically, the Philippines had set government policies to subsidize tertiary education and reformed standardized curricula to meet market demand abroad (Saguin, 2023). Notably, programs in healthcare and medicine are the leading educational programs in state-owned universities such as the University of the Philippines. Therefore, with government assistance, Philippine nurses and medical professionals have become the most prominent labor sector to migrate abroad. Consequently, a shortage of highly skilled nurses and the massive retraining of physicians to become nurses elsewhere has created severe problems for the Filipino health system, including the closure of many hospitals. It is critical to note that while Philippine nurses account for 27% of foreign-born registered nurses in the United States, domestically, the country was short of more than 200,000 healthcare workers as of September 2022, including more than 100,000 nurses.

Recommendations

This then brings the question: how should developing countries avoid the brain drain trap? The case study of the Philippine tertiary system highlight a key component of its brain drain problem, and that is the development of education policies that emphasize migration, rather than developing policies that will incentivize return migration, or brain circulation, such as lowering wages or providing temporary government assistance to help returning migrants to meet the same financial returns they would receive abroad (Shin & Moon, 2018). In addition, as observed from the OECD studies on tertiary education and migration trends, the motivation to migrate and the development of tertiary education within a country are in tandem, and therefore must be addressed. Policymakers in sending countries should also find a balance between investing in migration-led education, as well as primary and secondary education that are localized and prepare students for the conditions of the domestic market. My blog post titled, “Philippine Tertiary Education: An Emigration-Oriented and Market-Driven System,” further investigates the effects of a market-driven tertiary education system and its implications on the quality and access of tertiary education in the Philippines.

References

American Immigration Council. (2022, June 14). Foreign-born stem workers in the United States.https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/foreign-born-stem-workers-united-states#:~:text=As%20shown%20in%20Table%202,the%20STEM%20workforce)%20in%202019.

Anderson, S. (2023, May 23). New Immigration Data Point to larger U.S. workforce issues. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/stuartanderson/2023/05/22/new-immigration-data-point-to-larger-us-workforce-issues/?sh=6024bd391a91

Andira, A. (2023, June 11). Living in an integrated regional economy: Tackling Regional Brain Waste and brain drain. ASEAN-Australia Strategic Youth Partnership. https://aasyp.org/2023/06/11/living-in-an-integrated-regional-economy-tackling-regional-brain-waste-and-brain-drain/

Beltran, M. (2023, July 25). Philippines to lower bar for nurses as low pay drives many abroad. Al Jazeera

Kidjie Saguin (2023) The Politics of De-Privatisation: Philippine Higher Education in Transition, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 53:3, 471-493, DOI: 10.1080/00472336.2022.2035424

Getzoff, M. (2023, October 30). Most technologically advanced countries in the world 2023. Global Finance Magazine. https://gfmag.com/data/non-economic-data/most-advanced-countries-in-the-world/

ICMPD (February 2023). Same but different: Strategies in the global race for talent. https://www.icmpd.org/blog/2023/same-but-different-strategies-in-the-global-race-for-talent

OECD (2017), Enhancing migration-led development by facilitating investment in education, in Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265615-7-en.

OECD (2017). Migration and education in the Philippines. 2017 (137-157). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264272286-10-en.pdf?expires=1612566300&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=38B6DA2EC8F70C1B5B884A2DBE9309C1

OECD (2021, November 9). International migration of doctors and nurses. OECD iLibrary. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2021_d969fe68-en

Quartz. (2023, September 27). Rich countries are importing a solution to their nursing shortages-and poor countries are paying the price. https://qz.com/rich-countries-are-importing-a-solution-to-their-nursin-1850691166#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Philippine%20health,including%20more%20than%20100%2C000%20nurses.

U.S. Department of Defense. Industrial Capabilities Report to Congress | 2020 Annual Report (2021, January). https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jan/14/2002565311/-1/-1/0/FY20-INDUSTRIAL-CAPABILITIES-REPORT.PDF

Shin, G., & Moon, R.J. (2018). From Brain Drain to Brain Circulation and Linkage. https://aparc.fsi.stanford.edu/publication/brain-drain-brain-circulation-and-linkage

Trovall, E. (2023, September 11). Filipino nurses fill critical jobs as workforce shortage intensifies. Marketplace. https://www.marketplace.org/2023/09/11/filipino-nurses-fill-critical-jobs-as-workforce-shortage-intensifies/

Xavier de Souza Briggs, C. C. J., Ajay Agrawal, J. S. G., & Martin Neil Baily, E. B. (2023, September 8). The nation’s advanced industries are falling behind, but place-based strategies can help them catch up. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-nations-advanced-industries-are-falling-behind-but-place-based-strategies-can-help-them-catch-up/

Philippine Tertiary Education: An Emigration-Oriented and Market-Driven System

“Since I was a child, my parents instilled in me the importance of pursuing a nursing career in order to make a decent living and to move to the States. It was never really my dream, but I had a duty to fulfill. I had no prospects in the Philippines either way, so I had no choice but to move. It was because I had “utang na loob” (to be greatly indebted to another) for my family.”

This is a story shared by a University of The Philippines, Diliman alumni, and current RN at the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula, known as S.M. Hence, just like S.M., within the context of poor economic conditions, very limited high-income opportunities for Filipinos and the desire of children to help or “give back” to their families, many Overseas Filipino Workers, called OFWs, pursue college degrees or vocational training in order to work as healthcare workers overseas (Lorenzo, 2007), education, hospitality, engineers, general work, IT professionals, etc. (Digido, 2023).

The Creation of “Migrant Schools” and Market-Driven Curricula in Philippine Higher Education Institutions

Kidjie Saguin from the University of Amsterdam, in his study of the de-privatization of higher education institutions (HEIs) in the Philippines, correlates the Philippines’ economic ambitions and the re-centralization of government in the 1970s with the prevalent disparities in educational attainment, selective growth of certain educational programs, and the mass emigration of Filipino professionals, leading to the present labor gap crisis. With a growing demand for migrant workers in sectors such as healthcare and business abroad and coupled with a tight labor market domestically, the Philippine administration under Ferdinand Marcos heavily subsidized HEIs with a supplementary mandate to meet the standards of the Overseas Employment Program the administration established as part of a development program to increase GDP via remittances and to lift labor market strains (Saguin, 2023). As a result, Philippine HEIs transformed into what Saguin calls “Migrant Institutions.” Consequently, the key characteristic of some Philippine tertiary education in both private and public schools, notably nursing in this case, became the flexibility of its curricula designed to predict labor gaps in migrant destination countries and meet these labor demands abroad (Ortiga 2017, 490).

However, the de-privatization of HEIs in 1972 led to a divide in the quality and accessibility of tertiary education. Private institutions established selective curricula, often designed with elite and niche courses such as professional development and advanced medicine (Saguin 2023, 477). Public HEIs, on the other hand, experienced a massification phenomenon following the heavily subsidized higher education system, wherein students who have intention to work abroad are trained to obtain professional licenses in market driven courses such as nursing and business administration. On the other hand, non-competitive, alternative courses such as the social sciences produced no significant financial return to society and employment attainability, and therefore became underfunded and unpopular (Saguin, 478). Therefore, while enrollment has followed a general upward trend, the number of graduates has remained more constant, or even declined in some traditional disciplines, such as Humanities, Social Sciences, and the Arts (Battistella & Liao, 2013).

Figure 1: Highly educated individuals in the Philippines that are more likely to plan to emigrate

Examining the Quality of Nursing Programs in Philippine HEIs

Among other HEI programs, a growing demand for healthcare professionals and nurses abroad has led to a significantly higher enrolment in medical and nursing degree programs in Philippine HEIs (OECD/Scalabrini Migration Center, 2017). Thus, given this demand, the quality of academic healthcare programs increased.. A study conducted by Stella Appiah analyzed the quality of Philippine nursing education based on the following criteria: objectives and mission statements, curriculum and instruction, administration of nursing education, faculty development programme, physical structure and equipment, student services, and admission of students and the quality assurance system (Appiah, 2020). Almost 200 nursing faculty from 15 institutions participated in the study. Appiah’s study concluded that the quality of nursing programmes was perceived to be consistently high (a mean score of 96%). Therefore, well-trained graduates are in high demand on the international market and work overseas for higher salaries.

Conclusions and Recommendations

It can be observed that emigration-oriented and market-driven education, with centralized regulations and support from government subsidies, as well as limited opportunities for high income at home (Lorenzo, 2007) has led to the increased emigration of professionals. Nurses are motivated to move abroad by comparatively higher wages which support their family and themselves. This has created a feedback loop: The Philippines has continued to excel in its world renowned nursing programmes, with its top universities producing and sending out competent graduates both in the field of medicine to institutions all over the world (Appiah 2020).

But is this truly progress? According to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Goal 4, the answer is no.

The migration of the nation’s professionals and critical healthcare workers have resulted in a decline in human capital investment, commercialized health education and its attainability, and has caused a nation-wide depletion of skilled learning facilitators (Castro, 2017). Investing in human capital is a key component of achieving SDG 4. If higher education is selective and emigration-driven, this hinders growth as the returns to investment in education do not circulate domestically, but abroad. As a result, receiving countries are absorbing the highly valued skills and knowledge of Philippine professionals and healthcare workers. While migration has been seen by some as an opportunity for professional growth and enhancement and as a window for drafting more effective national and intercountry policy responses to HRH mobility (Castro 2017), a report conducted by the Scalabrini Migration Center concluded that return migration does little to build human capital since few emigrants acquire education abroad, nor do return migrates have economic incentive to return home with the pressurized labor market and lower value added to the domestic labor workforce as a prominent issue (OECD/Scalabrini Migration Center 2017).

Given the present state of the domestic healthcare system and the decreasing number of healthcare workers in the Philippines (brought about by their exodus to other countries), Philippine government policymakers should consider raising wages and social benefits for nurses and professionals to seek employment domestically upon graduation. Investing in training healthcare workers in rural and urban areas with local contexts and practices are equally as important in improving the domestic labor market. One primary example is a Public Health Leadership Development program that the University of the Philippines, Manila College of Nursing conducted in 2019 and ended in 2022, wherein 183 public healthcare workers from 17 regions, but rural and urban, participated in training courses that simulated local conditions and applied the Benner’s 5 Levels of Leadership Competencies as a metric of success (Tomanan et al., 2022). The design of this leadership training program, which required the participation of local and national government units, was to adapt to the demands of the Philippines’ health care constituency, leading to a better access to healthcare for a lot of Filipinos. Although further reports of its success are inaccessible publicly, this provides a valuable model in empowering rural healthcare workers and improving the quality and accessibility of healthcare education and training.

References

Appiah, S. Quality of nursing education programme in the Philippines: faculty members perspectives. BMC Nurs 19, 110 (2020).

Battistella, G., & Liao, K. A. S. (2013). Youth migration from the Philippines – Sustainable Development Goals Fund. https://www.sdgfund.org/sites/default/files/Youth-Migration-Philippines-Brain-Drain-Brain-Waste.pdf

Castro-Palaganas, E., et al. (2017). An examination of the causes, consequences, and policy responses to the migration of highly trained health personnel from the Philippines: the high cost of living/leaving—a mixed method study. Hum Resour Health 15, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0198-z

Digido. (2023, September 18). Top 10 in-demand jobs abroad for Filipinos: 2023. https://digido.ph/articles/ofw-loan/in-demand-jobs-abroad

Kidjie Saguin (2023) The Politics of De-Privatisation: Philippine Higher Education in Transition, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 53:3, 471-493, DOI: 10.1080/00472336.2022.2035424

Kristine Joy L. Tomanan, RN, MCD, John Joseph B. Posadas, RN, MSAHP, Miguel Carlo A. Fernandez, RN, Peter James B. Abad, RN, Msc, and Sheila R. Bonito, RN, DrPH, Tomanan, K. J. L., Posadas, J. J. B., Fernandez, M. C. A., Abad, P. J. B., & Bonito, S. R. (2022). Building Capacities for Universal Health Care in the Philippines: Development and Implementation of a Leadership Training Program. Philippine Journal of Nursing, 92(2). https://doi.org/http://www.pna-pjn.com/

Lorenzo, F. M. E., Galvez-Tan, J., Icamina, K., & Javier, L. (2007, June). Nurse migration from a source country perspective: Philippine Country Case Study. Health services research. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1955369/

OECE ilibrary. Migration and education in the Philippines. 2017 (137-157). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264272286-10-en.pdf?expires=1612566300&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=38B6DA2EC8F70C1B5B884A2DBE9309C1

Ortiga, Y. (2017). The Flexible University: Higher Education and the Global Production of Migrant Labor. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1113857

The integration of Ukrainian refugee children into Polish national education systems for a more socially cohesive society

UNICEF and its partner organizations are hard at work, designing programs and campaigns to integrate refugee children into host country schools. Their most recent initiatives following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the subsequent flood of Ukrainian refugees into Poland sheds light on swift and creative ways to enroll a greater number of refugee children in the national education system, with ongoing successes and challenges.

Reaffirming refugee access to Polish national schools

Of the 1.4 million Ukrainian refugees who initially fled to Poland in spring 2022, over 700,000 were estimated to be school-aged children (UNESCO, 2023). The UNICEF Refugee Response Office in Poland was established in record time in March 2022 to support families with resources while recovering from war (Kacprzak, 2023). The Polish government also quickly acted to provide Ukrainians with immediate access to the Polish education system (Sejm, 2022). Thus began the partnership between UNICEF, the Polish Ministry of Education and Science, NGOs, and the 12 municipalities with the highest concentration of Ukrainian refugees, to ensure that children were able to enroll in the national education system, accredited learning, or technical training (UNICEF, 2023).

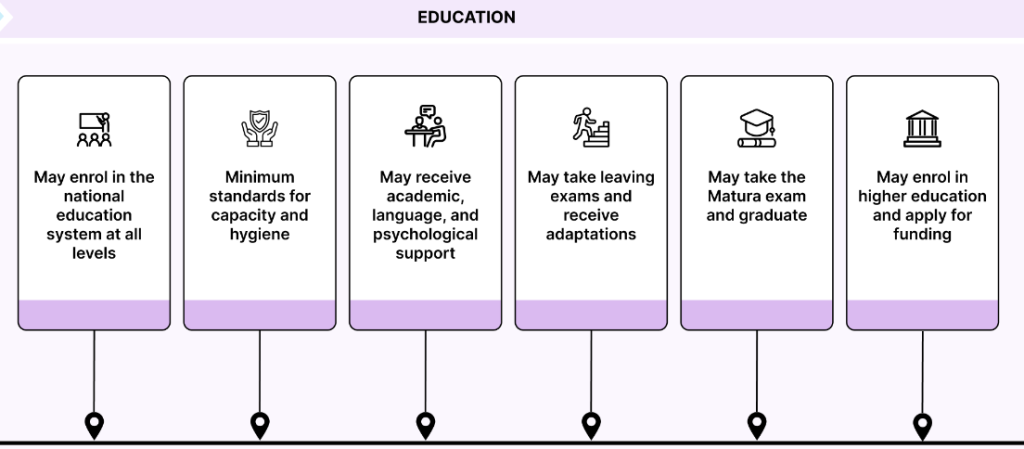

Ukrainian refugees in Poland follow this pathway for integration (UNESCO, 2023)

UNICEF initiatives to integrate Ukrainian children into Polish National Schools

UNICEF’s top priority has been to encourage Ukrainian families to enroll their children in Polish schools. They have also trained teachers in multicultural classroom management through a cutting-edge Learning Passport app, hired Ukrainian teaching assistants, and distributed school supplies to both Polish and Ukrainian children. Additional emergency support comes in the form of Blue Dot Hubs, Polish language summer camps, and interactive activities to ensure healthy social-emotional learning and relations with peers (UNICEF, 2023).

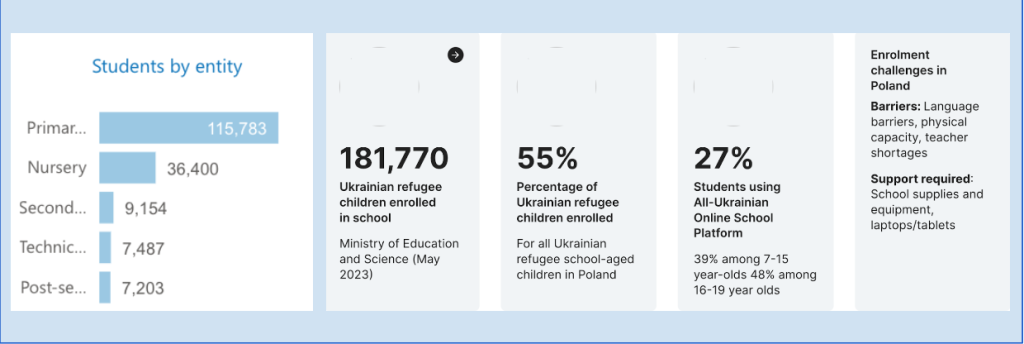

In spring 2022, UNICEF Poland and partners enrolled about 55%, or 185,000 of Ukrainian refugee children into Polish primary and secondary schools, while the other half continued their Ukrainian school studies online or did not enroll in school at all (UNICEF, 2022). Today, similar enrollment numbers remain, at about 36,400 in Polish nurseries and pre-schools, 115,783 in Polish primary schools, and only 9,174 in Polish secondary schools. Meanwhile, about 27% of Ukrainian children in Poland are fully enrolled in an “All-Ukraine Online School Platform,” 40% of which are 7-15 years old (UNHCR, 2023). This has created tensions between UNICEF and Ukrainian families, who have a difficult decision to make about whether or where to enroll their children and which system will have the most beneficial impacts.

UNESCO, 2023

Ukrainian Refugee Students by Powiat (Municipality) (UNHCR Operational Data Portal, 2023)

Promoting in-person, integrated education for social cohesion

UNICEF argues that Ukrainian families should send their children to Polish school, in-person, especially primary school. Monika Kacprzak, communications specialist at UNICEF Poland, shares that they are running a ‘back to the classroom’ campaign to help foster a sense of belonging, community, mental well-being, and social cohesion for Ukrainian students and their Polish peers. She emphasizes the use of ‘social cohesion’ instead of ‘integration,’ as the latter may create the perception of forced assimilation. Her team wants children to feel fully safe and welcomed in schools, while improving their mental health, social skills, and friendships with Polish children, which is best done in person. (Kacprzak, 2023). Kacprzak’s comments on social cohesion aligns with that of the United Nations Development Program (2007): social cohesion involves “a society where all groups have a sense of belonging, participation, inclusion, recognition, and legitimacy.” Kacprzak also reveals that enrolling more Ukrainian children in Polish schools can influence more funding to strengthen Polish national education capacities as a whole. Indeed, in January 2023, the Polish government did offer additional funding for schools supporting Ukrainian students, including funding to buy textbooks, materials, supplies, hire non-Polish assistants, psychologists, and other specialists to provide free psychological and pedagogical support for children (UNESCO, 2023).

“We invest in strengthening the Polish school system to expand access to quality education. Our investments benefit both Ukrainian and Polish children”

(UNICEF, 2023)

This shows how the pursuit of increasing access to education can, in fact, influence other development goals, such as SDG 16- “Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” (UN, 2015).”

Measuring social cohesion among Polish and Ukrainian children

While this is an ongoing crisis, initial takeaways have emerged. Enrolling Ukrainian children in Polish schools has positively impacted Poles’ tolerance, hospitality, and social relations. According to a poll conducted by Warsaw University and partners, about 80% of the Polish public supported Ukrainian children being admitted to Polish schools, and that support has not changed more than a year later (Krzysztoszek, 2023). Government officials, municipalities, teachers, and families have been very receptive to the UNICEF programs, especially because they were distributing materials equally to both Polish and Ukrainian children.

UNICEF has an ‘accountability to affected population’ team that has implemented feedback mechanisms into each program they’ve designed for Polish teachers, children, and Ukrainian children and their families to measure outcomes. They sent surveys and response forms to the 12 municipalities to gauge opinions about the programs, materials, and outcomes in their schools. They also receive SMS, phone calls, and emails with feedback from families. While the responses have not been published in any formal report, Kacprzak mentions some examples of strong social cohesion: Polish children inviting Ukrainian children to go the playground after school, Ukrainian parents’ involvement in school parent councils, Polish-Ukrainian collaborative art projects, and Polish students helping Ukrainian children read picture books in Polish. “It’s not easy to collect these answers, but we strongly encourage recipients of our programs to tell us if they’re working. We love to go into the field, do programmatic visits, speak with head teachers, and hear from students, “We are happy, we feel at home.” (Kacprzak, 2023).

Unfortunately, both respondents in the Warsaw University poll and Kacprzak admit seeing more anti-Ukrainian attitudes in other areas, such as less support for their access to jobs, healthcare and social services, a growing challenge this war prolongs. “We hope that this sentiment will decline, and that it will not trickle down into the welcoming atmosphere we’re trying to create in classrooms.” (Kacprzak, 2023).

Looking Forward

The constantly evolving nature of the War in Ukraine, the movement of refugees back and forth across the border, and relatively new education initiatives implemented by UNICEF and partners makes it challenging to collect and interpret comprehensive data about the impact of integrative education on overall social cohesion. Changes in social relations and institutions take time to develop, so it is not feasible to make grand conclusions in such a chaotic time. Further, Poland has experienced a teacher decline and shortage during this refugee crisis, from 518,746 teachers in 2020 to 512,102 in 2023 (Sas, 2023), which has created a strain on resources and quality of education (UNESCO, 2023).

Regardless of the longevity of the War in Ukraine and whether Ukrainian children decide to stay in the Polish education system, UNICEF and others’ work in the country has laid the foundation for further integration of other refugee populations. Recently, the European Union has reiterated its Member States’ obligations to integrate thousands of new refugees from outside of Europe into local institutions, which Poland has not had much experience with in the past. (Hajdukovic, 2023). The hope is that by providing and improving access and quality of inclusive, multicultural education for Ukrainian children, Poland will have a greater capacity, willingness, and tolerance to integrate refugee children from other countries and populations. This is the true test of how achieving education goals can further other development goals, namely SDG 16, to allow for more diverse populations to enter Poland and ‘feel at home.’

Works Cited

Hajdukovic, D. (2023, March 15). Integration of migrants and refugees: benefits for all parties

involved. Council of Europe, Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced

Persons. https://rm.coe.int/integration-of-migrants-and-refugees-benefits-for-all-parties-involved/1680aa9038

Kacprzak, Monika. (2023, November 23). UNICEF’s programs in Poland. Interview.

Krzysztoszek, Aleksandra. (2023, June 14). Poles less willing to help Ukrainian refugees: poll.

EURACTIV.pl.https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/poles-less-willing-to-help-ukrainian-refugees-poll/

Sas, Adriana. (2023, November 9). Number of teachers in Poland from 2008 to 2023. Statista

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1268829/poland-number-of-teachers/

Sejm of the Republic of Poland. (2022, March 12th). Ustawa o pomocy obywatelom

Ukrainy w związku z zbrojnym konfliktem na terytorium tego państwa (Act on

assistance to Ukrainian citizens in connection with the armed conflict on the territory of the country.)

https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220000583

United Nations Development Programme. (2007). Working Definition of Social Cohesion.

E-dialogue: Creating an Inclusive Society: Practical Strategies to Promote Social Integration. Division of Social Policy & Development. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/sib/inclusive_society/social%20cohesion.html

UNESCO. (2023, June 15). Poland’s education responses to the influx of Ukrainian refugees.

https://www.unesco.org/en/ukraine-war/education/poland-support

UNHCR. 2023. Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation, Poland: Refugee

Pupils from Ukraine. https://data.unhcr.org/en/dataviz/269?sv=54&geo=10781

UNHCR. (2023). Education Report 2023- Unlocking Potential: The Right to Education and

UNICEF (2022, September 1). As children return to school in Poland, UNICEF highlights

importance of getting those who’ve fled war in Ukraine back to learning.

https://www.unicef.org/eca/press-releases/children-return-school-poland-unicef-highlights-importance-getting-those-whove-fled

UNICEF. (2023, July 10). More than half of Ukrainian refugee children not enrolled in schools in