The integration of refugee children into national education systems for a more tolerant, cohesive society

Ola Pozor, International Policy & Development program

The all-time high number of refugee children in the world, 43.4 million and growing, (Ingram, 2023) speaks to the crisis-ridden era we live in and the urgency to provide children with quality education for a better future. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) specifies that refugee children are among those “who have been forced to flee conflict or persecution and cross international borders to seek safety”. Given the pressing issue of refugee children’s access to education, with “average enrollment rates at 38% at the pre-primary level, 65% at the primary level, and 41% at the secondary level” (UNHCR, 2023), the integration of refugee children into national school systems is a utmost priority among international organizations.

(UNHCR, 2023)

Integration for better access and inclusive global mindset

The obligation to provide primary education for refugees is stated in the 1951 UN Convention of Refugees, Article 22: “The Contracting States shall accord to refugees the same treatment as is accorded to nationals with respect to elementary education.” Since 2019, UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund, and its partners have shifted away from ‘parallel education systems’ (e.g. refugee camp settings), and have aimed to “find durable solutions for forcibly displaced populations geared toward inclusion into national systems” (UNICEF, 2022, p. 2). Thus, UNHCR and UNICEF have established country-specific offices and partnerships with national governments to prepare teachers, classrooms, and students for a more diverse, multicultural community and ‘side by side learning’ with host country students. UNICEF’s 2022 Children on the Move (CoTM): Inclusion in Education report explains how formative learning assessments, digital learning tools, remedial courses, and hiring refugee teachers for instruction in native languages, in countries like Uganda, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Sudan, Thailand, and Poland, “are helping enroll refugee children in schools and appropriate learning pathways, thus enabling them to transition to the national education system.” The modality of schooling varies from country to country, based on the host government’s policies, size of the refugee population, and availability of teachers/classrooms; ranging from fully in-person, online, day-shift, evening-shift, and hybrid learning environments.

UNICEF and national education systems’ goal is to not only better integrate and educate refugees, but also to foster greater tolerance, global-mindedness, and social cohesion of host country students with their new peers. “Approaches that build social cohesion help to overcome discrimination and bias against CoTM and support their inclusion and retention in education and learning locally” (UNICEF, 2022, xii). This reflects the UN’s long-held goals on education for tolerance, a key facet of quality education for all. The 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights, Article 19, affirms that “education should promote understanding, tolerance, and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups.” Similarly, Article 4 of the 1995 UNESCO Declaration on the Principles of Tolerance states:

“Education is the most effective means of preventing intolerance. The first step (…) is to teach people what their shared rights and freedoms are, so that they may be respected, and to protect those of others. It is necessary to (…) counter the cultural, social, economic, political and religious sources of fear and intolerance – major roots of violence and exclusion (…). This should help young people to develop capacities for independent judgment, critical thinking and ethical reasoning.”

Education that integrates both national and refugee youth is both a preventative and proactive strategy to include refugees in safe spaces, as well as to widen locals’ perspectives and welcoming attitudes toward populations fleeing conflict, violence, and persecution. Inclusive education also contributes to SDG Goal #16 – “Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” (UN, 2015).

Measuring outcomes: Quality education for social cohesion in blended schools

While “definitions of social cohesion vary across academic disciplines and between defining agencies, and the measurement of the concept is equally as wide-ranging” (McCollum, 2022), there is some consensus in the international development community. According to the UNDP (2007), social cohesion involves “a society where all groups have a sense of belonging, participation, inclusion, recognition, and legitimacy. (…) By respecting diversity, they harness the potential in their communities to grow together.” In 2022, UNHCR, World Bank, and FCDO commissioned 26 papers on social cohesion between refugees and host country citizens, using methodologies ranging from surveys of host nation citizens, lab-in-field games, social networking data, and sequential mixed methods to gauge the indicators of social cohesion (McCollum, 2022). In many of the studies, “scholars agree to certain key dimensions to measure social cohesion: trust in individuals, social participation, freedom from violence, and acceptance of diversity” (McCollum, 2022). UNICEF has also put forth 34 studies of integrated refugee learning to assess the social impact of their programs and identify areas for improvement.

While the report acknowledges that newly arrived refugee learners face risks, “including stereotyping and low expectations by teachers, bullying, and discrimination by staff or peers” (UNICEF, 2022, p. 19), the commissioned studies after time show several positive outcomes. For instance, increasing joint online schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic for refugees and local children in Nashatati, Jordan, “has positively impacted children and adolescents, with survey results demonstrating a 34% increase in the ability to deal with confrontation and not to resort to violence, and a 35% increase in willingness to play and work with students of different ages and nationalities.” (UNICEF, 2022, p. 34). In Turkey, using sport, recreation, art, and dance to unite students with different language capacities “has led to positive results in building a safer and more inclusive environment for CoTM.” (UNICEF, 2022, p 19). In Colombia, “enrolling both Colombian and Venezuelan children in Learning Circles remediation courses, designed to promote learning and empathy, conflict resolution, decision-making, and emotional self-regulation, has been key in avoiding xenophobia” (McCollum, 2022, UNICEF, 2022, p 26). Finally, a 2023 Council of Europe Resolution, “Integration of migrants and refugees: Benefits for all parties involved”, highlights how integration of refugees into educational and other public spaces “has promoted peace and social cohesion and subsequently decreased the cost of social conflict” (Hajdukovic, 2023).

There is still much work to be done to assess host country children’s attitudes toward their peers and vice versa, and while there are some small-scale studies assessing different integrated education models’ impacts on peaceful and inclusive societies, only time will tell as more of these programs unfold and more children are enrolled in host country schools.

Jordanian children and Syrian refugee children playing with Legos together through the Nashatati activity programme in local schools, designed to foster greater social cohesion (UNICEF, 2022).

Looking Forward

Integrating refugees into national education systems is a fairly new phenomenon in the international education realm and there is still little data to summarize global integration rates and overall impact on social cohesion and tolerance. However, country-specific programmes, reporting, and measurement of these SDG-16 related-outcomes, such as the ones above, sheds light on the potential for this approach to build more peaceful, tolerant societies, one classroom at a time.

Works Cited

Hajdukovic, D. (2023, March 15). Integration of migrants and refugees: benefits for all parties

involved. Council of Europe, Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced

Persons. https://rm.coe.int/integration-of-migrants-and-refugees-benefits-for-all-parties-involved/1680aa9038

Ingram, T. (2023, June 14). Number of displaced children reaches new high of 43.3 million.

UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/number-displaced-children-reaches-new-high-433-million

McCollum, K. (2022, November 16). Measuring social cohesion in contexts of displacement:

Do researchers agree? COMPAS School of Anthropology, Oxford University. https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/2022/measuring-social-cohesion-in-contexts-of-displacement-do-researchers-agree/

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (1995, November 16).

Declaration of Principles on Tolerance. UNESCO.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2022, February). Education, Children on the Move and

Inclusion in Education. UNICEF.

UNHCR. (2023, September 20). Five takeaways from UNHCR’s 2023 Education Report.

https://www.unrefugees.org/news/five-takeaways-from-unhcrs-2023-education-r

eport/#:~:text=The%20report%20reveals%20that%20average,percent%20at%20the%20tertiary%20level.

United Nations. (1951, July 28). Convention relating to the Status of Refugees.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-relat

United Nations Development Programme. (2007). Working Definition of Social Cohesion.

E-dialogue: Creating an Inclusive Society: Practical Strategies to Promote Social Integration. Division of Social Policy & Development. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/sib/inclusive_society/social%20cohesion.html

The integration of Ukrainian refugee children into Polish national education systems for a more socially cohesive society

UNICEF and its partner organizations are hard at work, designing programs and campaigns to integrate refugee children into host country schools. Their most recent initiatives following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the subsequent flood of Ukrainian refugees into Poland sheds light on swift and creative ways to enroll a greater number of refugee children in the national education system, with ongoing successes and challenges.

Reaffirming refugee access to Polish national schools

Of the 1.4 million Ukrainian refugees who initially fled to Poland in spring 2022, over 700,000 were estimated to be school-aged children (UNESCO, 2023). The UNICEF Refugee Response Office in Poland was established in record time in March 2022 to support families with resources while recovering from war (Kacprzak, 2023). The Polish government also quickly acted to provide Ukrainians with immediate access to the Polish education system (Sejm, 2022). Thus began the partnership between UNICEF, the Polish Ministry of Education and Science, NGOs, and the 12 municipalities with the highest concentration of Ukrainian refugees, to ensure that children were able to enroll in the national education system, accredited learning, or technical training (UNICEF, 2023).

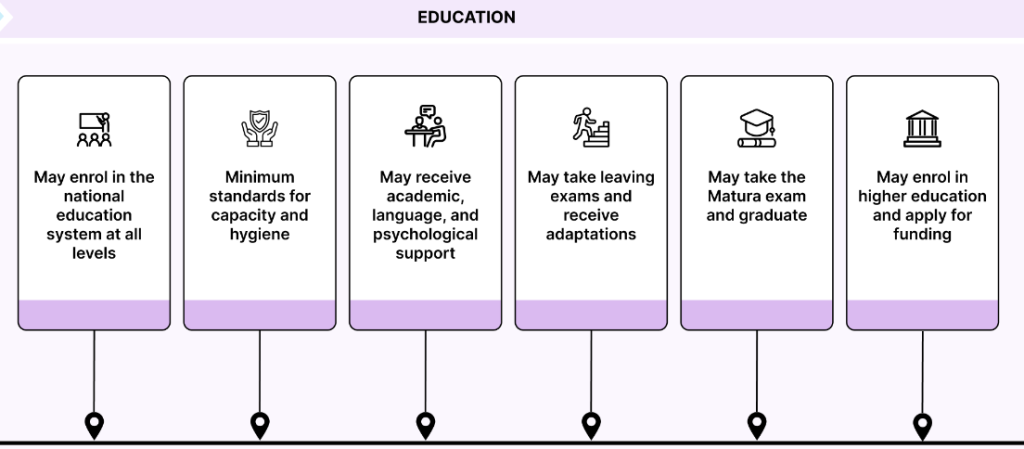

Ukrainian refugees in Poland follow this pathway for integration (UNESCO, 2023)

UNICEF initiatives to integrate Ukrainian children into Polish National Schools

UNICEF’s top priority has been to encourage Ukrainian families to enroll their children in Polish schools. They have also trained teachers in multicultural classroom management through a cutting-edge Learning Passport app, hired Ukrainian teaching assistants, and distributed school supplies to both Polish and Ukrainian children. Additional emergency support comes in the form of Blue Dot Hubs, Polish language summer camps, and interactive activities to ensure healthy social-emotional learning and relations with peers (UNICEF, 2023).

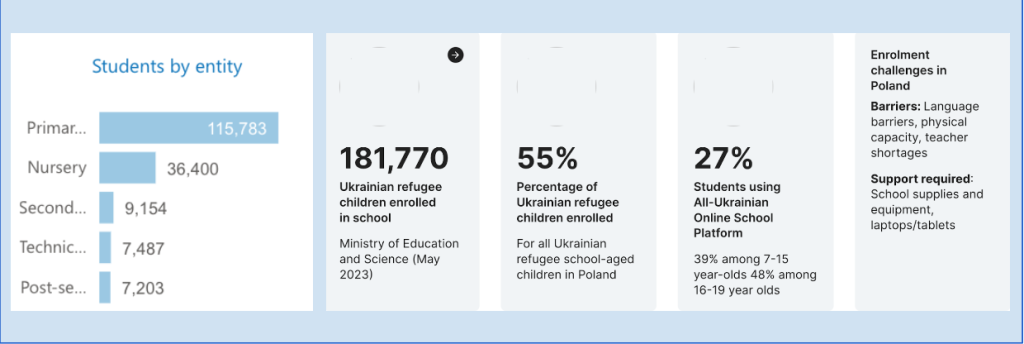

In spring 2022, UNICEF Poland and partners enrolled about 55%, or 185,000 of Ukrainian refugee children into Polish primary and secondary schools, while the other half continued their Ukrainian school studies online or did not enroll in school at all (UNICEF, 2022). Today, similar enrollment numbers remain, at about 36,400 in Polish nurseries and pre-schools, 115,783 in Polish primary schools, and only 9,174 in Polish secondary schools. Meanwhile, about 27% of Ukrainian children in Poland are fully enrolled in an “All-Ukraine Online School Platform,” 40% of which are 7-15 years old (UNHCR, 2023). This has created tensions between UNICEF and Ukrainian families, who have a difficult decision to make about whether or where to enroll their children and which system will have the most beneficial impacts.

UNESCO, 2023

Ukrainian Refugee Students by Powiat (Municipality) (UNHCR Operational Data Portal, 2023)

Promoting in-person, integrated education for social cohesion

UNICEF argues that Ukrainian families should send their children to Polish school, in-person, especially primary school. Monika Kacprzak, communications specialist at UNICEF Poland, shares that they are running a ‘back to the classroom’ campaign to help foster a sense of belonging, community, mental well-being, and social cohesion for Ukrainian students and their Polish peers. She emphasizes the use of ‘social cohesion’ instead of ‘integration,’ as the latter may create the perception of forced assimilation. Her team wants children to feel fully safe and welcomed in schools, while improving their mental health, social skills, and friendships with Polish children, which is best done in person. (Kacprzak, 2023). Kacprzak’s comments on social cohesion aligns with that of the United Nations Development Program (2007): social cohesion involves “a society where all groups have a sense of belonging, participation, inclusion, recognition, and legitimacy.” Kacprzak also reveals that enrolling more Ukrainian children in Polish schools can influence more funding to strengthen Polish national education capacities as a whole. Indeed, in January 2023, the Polish government did offer additional funding for schools supporting Ukrainian students, including funding to buy textbooks, materials, supplies, hire non-Polish assistants, psychologists, and other specialists to provide free psychological and pedagogical support for children (UNESCO, 2023).

“We invest in strengthening the Polish school system to expand access to quality education. Our investments benefit both Ukrainian and Polish children”

(UNICEF, 2023)

This shows how the pursuit of increasing access to education can, in fact, influence other development goals, such as SDG 16- “Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” (UN, 2015).”

Measuring social cohesion among Polish and Ukrainian children

While this is an ongoing crisis, initial takeaways have emerged. Enrolling Ukrainian children in Polish schools has positively impacted Poles’ tolerance, hospitality, and social relations. According to a poll conducted by Warsaw University and partners, about 80% of the Polish public supported Ukrainian children being admitted to Polish schools, and that support has not changed more than a year later (Krzysztoszek, 2023). Government officials, municipalities, teachers, and families have been very receptive to the UNICEF programs, especially because they were distributing materials equally to both Polish and Ukrainian children.

UNICEF has an ‘accountability to affected population’ team that has implemented feedback mechanisms into each program they’ve designed for Polish teachers, children, and Ukrainian children and their families to measure outcomes. They sent surveys and response forms to the 12 municipalities to gauge opinions about the programs, materials, and outcomes in their schools. They also receive SMS, phone calls, and emails with feedback from families. While the responses have not been published in any formal report, Kacprzak mentions some examples of strong social cohesion: Polish children inviting Ukrainian children to go the playground after school, Ukrainian parents’ involvement in school parent councils, Polish-Ukrainian collaborative art projects, and Polish students helping Ukrainian children read picture books in Polish. “It’s not easy to collect these answers, but we strongly encourage recipients of our programs to tell us if they’re working. We love to go into the field, do programmatic visits, speak with head teachers, and hear from students, “We are happy, we feel at home.” (Kacprzak, 2023).

Unfortunately, both respondents in the Warsaw University poll and Kacprzak admit seeing more anti-Ukrainian attitudes in other areas, such as less support for their access to jobs, healthcare and social services, a growing challenge this war prolongs. “We hope that this sentiment will decline, and that it will not trickle down into the welcoming atmosphere we’re trying to create in classrooms.” (Kacprzak, 2023).

Looking Forward

The constantly evolving nature of the War in Ukraine, the movement of refugees back and forth across the border, and relatively new education initiatives implemented by UNICEF and partners makes it challenging to collect and interpret comprehensive data about the impact of integrative education on overall social cohesion. Changes in social relations and institutions take time to develop, so it is not feasible to make grand conclusions in such a chaotic time. Further, Poland has experienced a teacher decline and shortage during this refugee crisis, from 518,746 teachers in 2020 to 512,102 in 2023 (Sas, 2023), which has created a strain on resources and quality of education (UNESCO, 2023).

Regardless of the longevity of the War in Ukraine and whether Ukrainian children decide to stay in the Polish education system, UNICEF and others’ work in the country has laid the foundation for further integration of other refugee populations. Recently, the European Union has reiterated its Member States’ obligations to integrate thousands of new refugees from outside of Europe into local institutions, which Poland has not had much experience with in the past. (Hajdukovic, 2023). The hope is that by providing and improving access and quality of inclusive, multicultural education for Ukrainian children, Poland will have a greater capacity, willingness, and tolerance to integrate refugee children from other countries and populations. This is the true test of how achieving education goals can further other development goals, namely SDG 16, to allow for more diverse populations to enter Poland and ‘feel at home.’

Works Cited

Hajdukovic, D. (2023, March 15). Integration of migrants and refugees: benefits for all parties

involved. Council of Europe, Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced

Persons. https://rm.coe.int/integration-of-migrants-and-refugees-benefits-for-all-parties-involved/1680aa9038

Kacprzak, Monika. (2023, November 23). UNICEF’s programs in Poland. Interview.

Krzysztoszek, Aleksandra. (2023, June 14). Poles less willing to help Ukrainian refugees: poll.

EURACTIV.pl.https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/poles-less-willing-to-help-ukrainian-refugees-poll/

Sas, Adriana. (2023, November 9). Number of teachers in Poland from 2008 to 2023. Statista

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1268829/poland-number-of-teachers/

Sejm of the Republic of Poland. (2022, March 12th). Ustawa o pomocy obywatelom

Ukrainy w związku z zbrojnym konfliktem na terytorium tego państwa (Act on

assistance to Ukrainian citizens in connection with the armed conflict on the territory of the country.)

https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220000583

United Nations Development Programme. (2007). Working Definition of Social Cohesion.

E-dialogue: Creating an Inclusive Society: Practical Strategies to Promote Social Integration. Division of Social Policy & Development. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/sib/inclusive_society/social%20cohesion.html

UNESCO. (2023, June 15). Poland’s education responses to the influx of Ukrainian refugees.

https://www.unesco.org/en/ukraine-war/education/poland-support

UNHCR. 2023. Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation, Poland: Refugee

Pupils from Ukraine. https://data.unhcr.org/en/dataviz/269?sv=54&geo=10781

UNHCR. (2023). Education Report 2023- Unlocking Potential: The Right to Education and

UNICEF (2022, September 1). As children return to school in Poland, UNICEF highlights

importance of getting those who’ve fled war in Ukraine back to learning.

https://www.unicef.org/eca/press-releases/children-return-school-poland-unicef-highlights-importance-getting-those-whove-fled

UNICEF. (2023, July 10). More than half of Ukrainian refugee children not enrolled in schools in