I. Integrated language skills

1. Mock auction

Language objectives: Persuasive skills through positive description

Level: Lower-intermediate upwards

Procedure:

1. Learners are told they are left with only one object/possession (they can choose what it is), and write its name on a slip of paper.

2. Jumble the slips and redistribute them.

3. Ask the learners to make a list of the qualities of their object – its desirability, usefulness and aesthetic value.

4. Ask students to make their own mock money (divide a clean sheet of paper into 10 rectangles and write the agreed value on each.

5. Each student then auctions their own object. They should try to get as high a price as possible. Teacher may need to model an auction. Learners should understand they need to use inflated comments on each sale, using the list made at step 3 as prompts. They will also need to urge buyers if bidding is slow or flagging.

Example: “Come on ladies and gentlemen… This bag is made of the best grade leather. You can see how soft it is and it really is chic! Do I hear $150?”

5. After the bidding has finished, find out:

• how many people bought more than one thing

• whether anyone bought nothing

• who spent the most

• who spent the least

6. Finally encourage learners to discuss why they decided to pay what they did for different things, or why they decided not to buy.

Follow-up writing (This activity can be assigned as homework and displayed in the next class session)

1. Students are told to choose an object that they own but rather dislike and write an advert emphasizing its positive qualities, suitable for placing in a local shop window (or facebook school marketplace page).

E.g., This is an advert for a chair posted on MIIS Marketplace “Available for drop off. Totally collapsible and very comfy chair. Washable covers. Pillows included.”

b. When everybody has finished, place the adverts around the room and give learners time to browse and to note down any articles they are particularly interested in/

3. Finally ask learners to form groups of 3-5 and to compare what they are interested in buying.

Note: This activity can be used for large-size classes. Students will sit in groups, choose an object they want to auction and make a list of exaggerating description. Each team will have one time auction to get their object sold.

2. Jigsaw reading

Language objectives: Critical reading skills and ability to orally summarize the ideas in the assigned readings to other students in group.

Level: Intermediate upwards

Note: This activity is often applied to a big number of required readings, either short or long in different types of text, and is assigned as home-work for the next classroom discussion session.

Procedure:

1. Ask students to form groups of 3-4. If there are fewer than 3-4 readings for the whole class session, let learners assign which reading among themselves, normally each in charge of one text. If there are more readings, e.g., 5-7, allow students to choose the text they like to read (there should be a maximum of registration for each text, or else, many may choose the same text), then number them from 1 to 7 and ask them to sit in group 1, group 2, …, group 7.

2. Each group member reads his/her own text at home. While they are reading, they need to address several questions as follows:

– The main ideas of the text

– Two points made in the text you find most useful or interesting (students can talk more than two if they want)

– One thing you don’t really like (students can talk more than two if they want)

3. Students sit in their group and summarize their answers for those questions. Other members can share opinions and discuss further questions to clarify information.

3. Role and language

Language objective: Casual conversation

Level: Lower-intermediate upwards

Procedure:

1. Writing on the board (giving or eliciting) a list of contrasting human conditions. E.g.:

Old person …….. Young person

Lazy person …….. energetic person

Thin person …….. fat person

Driver …….. Passengers

City person …….. Country person

2. Write a topic of casual conversation on the board, something like the weather, clothes price, food price, our schools, traffic problems in the city, etc.

3. Ask students to make pairs and choose roles for their pair.

4. Take two contrasting roles not being used by the learners and then model them.

5. Pairs hold a conversation on the agreed topic with each person in their role.

E.g. A conversation is an upper-intermediate group between an old and young person on traffic problems might run as follows:

Old: Look at all these cars!

Young: Most of them’ve only got one person in them!

Old: In my days, we used to cycle everywhere, or walk.

Young: I suppose people need to travel further these days. …

4. Information gaps

Objective: Contextualised communication; Making questions and answers

Procedure:

1. The teacher gives a handout to each student. These handouts have the same content, but some of them have different erased words or phrases.

2. The teacher gives instruction: students need to stand up, move around and ask other students if they know the erased words in their handout by asking the questions for the blanks like “Do you know the population of city (A)?”. If their friend knows the answers (i.e., the words are not erased in the partner’s handout), they will say it, or else, they say “I don’t know.” and move to the next friend.

3. The students carry out the activity, and the teacher monitors their interaction and make sure they are not using their L1 language.

In this activity, learners are given a context in which they need the answers for the words erased in their handout, so they need to interact with their friends who may have those words to identify which words were taken out.

5. Qualities for life: Deciding what qualities help you get the best out of life

Language focus: Words and phrases describing qualities that enhance enjoyment of life

Objective: Speaking; listening

Level: Intermediate upwards

Procedure:

1. Ask the class to think of things about themselves and others that enhance their enjoyment of life. They might be personality, abilities, or attributes.

2. After 5 minutes for brainstorming, write up as many as the class can think of on the board.

3. Ask learners to choose one quality that they think would enhance their own enjoyment of life. They should tell nobody at this stage.

4. The teacher chooses a quality and pretends to hold it in her hands. She chooses a learner and gives him/her the quality as a present, saying, e.g.

Teacher: I’d like to give you the ability to do break dancing if you don’t already have it.

Student: Thank you – and I’d like to give you the ability to calm down in difficult and scary moments.

The teacher thanks the learner, takes the new gift in his/her hands and then looks for someone else to pass the new gift on to, and continues the next exchange.

5. When learners understand the game rules, ask everybody to get to stand up ad walk around exchanging “gifts”. When everybody has spoken to most other people (in about 15 minutes), ask learners to return to their seats.

6. Optional (for follow-up activities)

Ask learners which of all the gifts they were given they would most like to keep and (1) volunteer to share orally with the whole class; and/or (2) write a positive brief note and stick it to a place in the classroom, referred as “Qualities for life”

Freer follow-up activity can involve contextualized prompts. Teacher can show the students a short story focusing a specific character’s life, then asks them to think of what qualities that character would find most useful in life and why.

Note: Doing this activity, adult learners may create valuable qualities and can use good vocabulary to talk about the desirable qualities. It is also very meaningful to involve children. Young learner may have simpler ideas, but it would be a very good opportunity to talk to them about good social and personal values. Learners can learn more deeply about one another when sharing these values together.

II. Vocabulary

6. Shiritori (from Dana and Andrew’s activity for PTF)

Objectives: warm-up, vocabulary

Procedure:

Students make pairs and listen to game rules: each player is given a random letter by their partner and must pick a word beginning with that letter (their “start” word can also be their first name or anything related to themselves, e.g., their favorite food, flower, drink, etc.). In one minute, the player keeps coming up with as many words starting with the last letter of the previous word as possible while the other keeps timing. After one minute, they switch roles. The one who has more words is the winner.

Words created must:

– be not proper nouns

– have at least 4 letters

– not be repeated

Note: In pair, students can take turn to come up with their own word starting with the last letter of the previous word written by their partner, and the game can occur in 1-2 minutes. The one who has more words is the winner. The game may also finish before the time limit if no players can come up with the next new word.

7. Letters to Words

Objectives: Warm-up, vocabulary

Procedure:

1. Students make pairs

2. Teacher gives the pairs a handout with a list of words of ten letters, asking students to break each word into two words of five letters each. The word can be a proper name and makes sense in current English vocabulary.

Note: The game can also have a completely different version. Students are given a list of abbreviations that they have learned or known and required to work out in pairs what the abbreviations stand for.

8. Definition Matching

Objective: review, warm-up, vocabulary, speaking, listening

Levels: All levels

Procedure:

The teacher gives each group of 4-5 students two envelopes; one contains the vocabulary (words), concepts or terminology, and the other contains the definitions, examples or descriptions to illustrate the vocabulary/concepts. Teacher can give just one envelope for both words and definitions but in two different colors. In their group, the students take turn to pick up a piece giving the description and the other students, if they can say the target word/concept, will get the pair of word-definitions. Who can get the most is the winner.

Note: This activity is normally used as a review of the vocabulary/concepts the students have learned so far. It can also be used as a warm-up activity to help review the knowledge but also to give students a break at the same time. Depending on the difficulty of the vocabulary and how much the teacher wish the students to review, the activity can be modified from easy to relatively difficult, accommodating all levels of learners.

III. Grammar

9. Bad English (Our activity for Pedagogical Trade Fair)

Objective: Learner ability to spot and correct grammatical and vocabulary errors; Build up learner confidence

Level: Intermediate upwards

Procedure:

1. Teacher collects some signs in real-life use from the surrounding environment or from the Internet. The signs should not be ambiguous (i.e., having enough context as a clue for students to be able to identify the error), and they should also show the language errors from native speakers, not only from international use.

2. Teacher asks students: -what is the problem with the sign?; – how do you think it should be corrected; – explain your reasons. Teacher can model one example with the whole class, and have the students work in groups on the signs (if there are quite many signs, divide 2-3 signs to each group for all the work to be done)

3. Teacher then shows some examples of student work/assignments but leave it anonymous. The students need to spot the errors and suggests ways to correct them. In this way, students have an opportunity to look at their erroneous use of language, listen to others’ feedback but do not lose confidence when their work is shown.

Note: Doing this activity, students can see they may make mistakes, but they are also capable of spotting and correcting errors including ones made by native speakers of the target language.

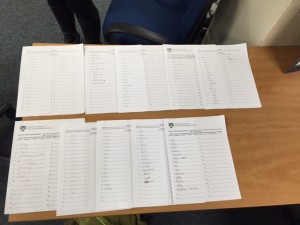

10. Self-correct grammar homework (From my Language Analysis class)

Objective: – Students gain deeper understanding of the knowledge acquire through seeing why their answers might be not appropriate and being exposed to other ways examining the same problems; – Raise more linguistic awareness; – Build up confidence and motivation

Level: Lower-intermediate upwards

Procedure:

This activity should be used for Grammar course and linguistic courses which often included a lot of grammar exercises. Before giving any textbook exercises to students, teacher gives them the exercises Key (which is often not included in student textbook). The students are asked to first do the exercises themselves (based on what they understand from reading the textbook, lectures and class materials), then compare their answers to the sample answers given in the Key and correct them. By the deadline, the students are supposed to give the corrected version of their homework to the teacher. The teacher will mark and give feedback on student work of correction and comparison. There are some questions may suggest a varied answer and the students should also give those exercises a tick to show they have read the ideas suggested in the Key. I found it really useful and enjoyable when doing this type of activity myself in the Language Analysis class. Therefore, I would love to use it in my Basic or Advanced grammar (involved with Morphology and Syntax) classes, or even Phonetics or Phonology classes. Doing this activity, students will not follow the conventional way of doing grammar drill practice, find it more challenging and more motivated to engage in grammar classes.

IV. Information review (adaptable for Vocabulary learning)

11. Jeopardy

Objectives: Review, have fun

Teaching aids: Paper pieces with information categories on them, paper pieces of score numbers (100, 200, 300, 400, and 500, or any other scale the teacher likes)

Procedure:

1. Teacher stick the categories on the board/wall, and the scores underneath (each categories include the five score bands)

2. Teacher has students form groups of 3-5 depending on class size. Each group nominates a leader who is in charge of saying the category and the score level the group agree on.

3. Teacher randomly picks up the group taking the first turn to play the game. Each group takes turn to choose their own category and score level. Teacher will read the question (e.g., definitions, illustrative examples, problems/situations…) that level, and the group has 30 seconds to discuss the answer. If they cannot give the answer within the time limit or fail to give the right answer, the next group on their left will get the chance to answer the question until the right one is given.

4. The class plays the game until all questions are solved. The group with the highest score is the winner.

Note: This activity can be used to review information/knowledge (e.g., theories, concepts, definitions, …), vocabulary, or grammar (e.g., names, use, exceptions of grammatical points). As a review activity, it can be played at the end of units, chapters, sections, and when the course finishes. The game rule can also vary. For every turn, a student in the class is randomly selected to choose the category and score level. All the teams have 30 seconds to think of the answer and write it on their team boards, and then hold them up to the teacher when time runs up. Every team with the correct answer gets the score, and loses the same amount of points with an incorrect answer. For this Jeopardy version, the teacher can make fewer questions, but the former version is more appropriate with teacher’s goal of reviewing a large amount of information. Playing this game enables students to memorize the main points (essential information) they need to review.

12. Warm-up with Socrative short questions and answers (from my MALL course)

Objective: Warm-up and activate students’ knowledge of previous lesson; Individual contribution

Level: All

Procedure:

The teacher uses the app/software Socrative, which is free and simple to use without much of the teacher’ preparation, to form some short questions that help review the content taught in the previous lesson. The teacher first creates the accounts for all students in his/her class, they then have a username and password to log in the site. When they log in their account in class from the Socrative app on their mobile phone, they will see the questions in sequence and they have limited time (decided by the teacher) to answer each question. They are only advanced to the next question if they finish the current one. After an appropriate time allotted for the questions, the teacher can show to the whole class (using the projector connected with his/her mobile phone/laptop/iPad) the answers submitted for each questions. They can collectively look at the answers and share their opinions.

Note: This activity allows the teacher design quick questions for warm up and lesson review in an efficient way. Socrative is also used during the lesson if some quick questions are necessary to collect students’ opinions about a class topic. Also, as the answers are presented when the teacher chooses to display them and quick, short answers are required for the next question to appear, all students have to make their contribution (although not to all the questions). Besides, every question will be answered from at least several learners.

Minh.